Similar Posts

(Editor’s Note. This essay builds upon our earlier article about Fr. Zinon by Aidan Hart. This article explores Fr. Zinon’s often original and controversial beliefs about the Church, and how his independent thinking inspired his art. By posting this article, the OAJ does not mean to imply endorsement of Fr. Zinon’s ideas, but rather to explore the motivations of this highly influential iconographer. It is well worth considering that many of the recent archaizing fashions in Orthodox liturgical art do not exist in isolation from ecclesiology.)

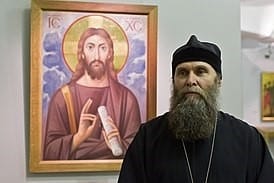

Fr Zinon (Teodor) is widely regarded as one of contemporary Russia’s most important iconographers. Active since the 1970s, his creative work came to a climax in 2013, with completion of the lower church of the Feodorovskii Sobor in St Petersburg. Earlier in his career, he had executed icons for three of Russia’s major religious centers — the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery (the only Russian monastery never to have been closed during the Soviet period), the Holy Trinity-St Sergius Lavra (Russia’s most ancient and famous monastery), and the Danilov Monastery in Moscow (where the Patriarchate has its offices). Fr Zinon has also received important commissions from outside of Russia. His icons can be found today in Belgium, Finland, England, and Austria, and on Mt Athos, not only in Orthodox but also in Catholic and Protestant churches. Iconographers influenced by his techniques and ideas have been active in the United States.[1]

Western scholarship on Fr Zinon has discussed the evolution of his iconographic styles and techniques.[2] This essay focuses on the religious vision that drives Fr Zinon’s work.[3] Fr Zinon argues that the mission of the Orthodox Church — and therefore the purpose of its iconography — is to draw the world into a vision of divine beauty. He fears, however, that the Russian Church has largely failed in this task, despite the freedom that it has enjoyed since the fall of communism. Indeed, Fr Zinon sees his work as offering a stark alternative to the iconographic style and the ecclesial self-understanding that otherwise predominate in Russia’s Putin-era Church.[4] Through his iconography, he seeks to open up a space in which people experience divine transcendence and human solidarity.

Fr Zinon’s Biography

Fr Zinon was born Vladimir Mikhailovich Teodor on October 12, 1953, in Pervomaisk (“May 1st”), an industrial town several hours north of Odessa, Ukraine.[5] His father worked on a collective farm as a sheepherder and, in the 1960s, received several state honors for his achievements as a socialist brigade leader.[6] Fr Zinon’s mother was an accountant. Although neither of his parents were believers, Fr Zinon was baptized as a baby, a popular practice that endured in the Soviet Union despite the state’s official atheism. He recalls his grandmother taking him to church when he was three or four years old: “Never before had I encountered such an unusual place: quiet, beautiful, and inexplicably mysterious.”[7]

As a boy, Fr Zinon quietly became interested in iconography. At home, he found a dusty copy of the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Jewish and Christian Bibles, and began looking up some of the figures and events depicted in icons in local churches and museums. In 1969, at age 15, he entered the Odessa Art Institute. During his second year of study, his landlord gave him a copy of the Gospels. By the beginning of Lent in 1971, Fr Zinon had made a conscious decision to reject Soviet ideology and to enter into church life.[8] He began on his own to copy ancient icons from reproductions in books. Soon he was assisting in painting icons in the Orthodox cathedral in Odessa, where he met Pimen, Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, who had a residence nearby. For his graduate project at the art institute, Fr Zinon proposed copying a Rublev triptych, but his supervisor insisted, instead, on a Socialist Realist scene.

Already at this early age, Fr Zinon was aware that his iconographic interests placed him in a precarious position in Soviet society. Although by the 1970s the state was shipping few Christians off to the gulag, it was still actively promoting antireligious education and propaganda, and was discouraging young people, in particular, from associating with the Church. As Fr Zinon later noted, “according to the Soviet Constitution, the painting of icons was equivalent to religious and, therefore, anti-Soviet propaganda. It was a crime for which one could go to prison.”[9]

Fr Zinon decided that he could best pursue his calling to iconography by becoming a monk — as he would later say, “To leave aside everything for Christ.”[10] In 1973, he briefly visited the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery, whose abbot, Archimandrite Alipii (Voronov), was a talented iconographer. However, Fr Zinon first had to complete two years of mandatory military service. Because of his artistic abilities, the army assigned him to execute generic decorative paintings to hang in military buildings in Odessa. After his discharge, he worked again on icons in the Odessa cathedral. When he learned about an Orthodox holy elder across the border in Russia, he decided to ask his blessing to enter, at last, into monastic life.[11]

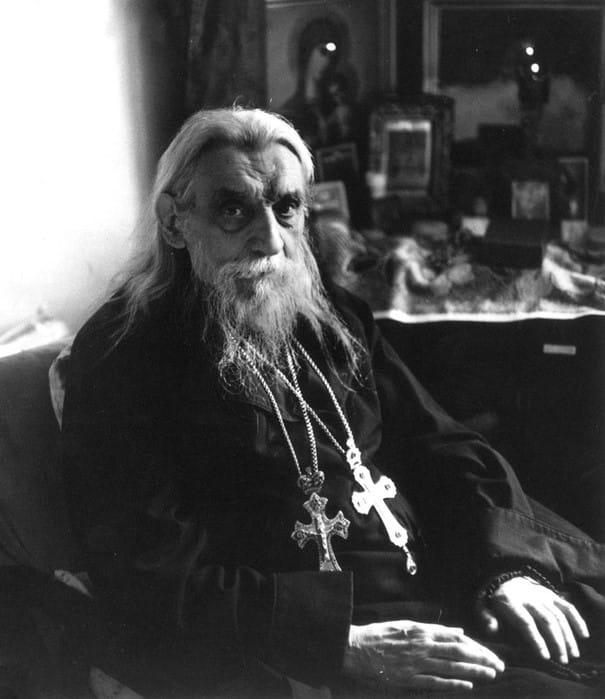

This elder was Seraphim Tiapochkin, a priest in the small town of Rakitnoe, near Belgorod. Fr Seraphim had survived nearly fifteen years in prison camps and internal exile before his release in 1955. He soon gained a popular reputation for his spiritual wisdom and inspired preaching, and believers from throughout the Soviet Union began making pilgrimage to Rakitnoe to ask for his prayers and counsel. Fr Zinon found in Fr Seraphim a remarkable embodiment of unconditional Christian love: “Here was a person without an ounce of resentment in him. Not once did I hear Fr Seraphim condemn a person or call anyone out. . . . He received everyone with love—I was no exception.”[12]

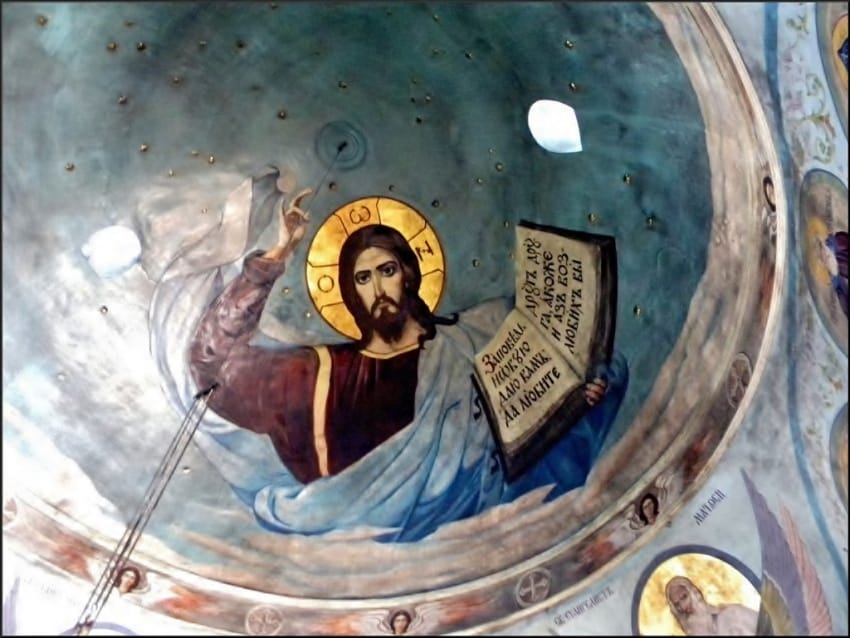

Fr Seraphim was in the process of restoring the half-ruined St Nicholas Church in Rakitnoe. Upon learning that Fr Zinon was an iconographer, he invited him to execute frescoes for the altar area and for the central axis of the church. Although Fr Zinon regarded the achievements of Andrei Rublev in the early fifteenth century as most fully realizing Orthodox iconographic canons, he knew that this style was unfamiliar and even repulsive to many ordinary believers, who were used to the iconographic style of the Synodal period, a pictorial sentimentalism influenced by nineteenth-century French and Italian Catholic church art. Fr Zinon therefore chose to paint in the style of Viktor Vasnetsov, who at the end of the nineteenth century had sought to retrieve Russia’s distinctive tradition of iconography but by means of an art nouveau style that would appeal to popular tastes. The Pantocrator that Fr Zinon painted for the dome in Rakitnoe was a close copy of Vasnetsov’s work for St Vladimir’s Cathedral in Kiev, which Fr Zinon had visited.

In the fall of 1976, Fr Zinon entered the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery, was ordained as deacon and then priest, and painted icons, now more in the style of Rublev, for the monastery churches. In 1978, Patriarch Pimen, enthusiastic about Fr Zinon’s efforts to recover Russia’s great iconographic traditions, had him transferred to the Holy Trinity-St Sergius Lavra. There Fr Zinon became acquainted with Iulianna Sokolova (1899–1981), who during the harshest years of Stalinist repression had quietly preserved and transmitted ancient Russian understandings and techniques of iconography.[13] In 1983, the Patriarch had Fr Zinon transferred again, this time to the Danilov Monastery in Moscow, which the government had returned to the Church in preparation for celebrating, in 1988, the millennium of Orthodoxy among the Eastern Slavs. Fr Zinon had particular responsibility for the lower church of the Uspenskii Sobor (Dormition Cathedral).

In 1985, after completing icons for a church in the Vladimir Region, Fr Zinon returned to the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery. He now began to turn away from the era of Rublev to earlier periods of Russian iconography influenced by Byzantine church traditions. In 1994, the government returned Pskov’s Mirozhskii Monastery to the Church on the condition that Fr Zinon organize a school of iconography there. The school quickly attracted students from both Russia and abroad. Moreover, Fr Zinon was now able to travel to the West. He offered seminars on iconography in Italy and France and received commissions from Western European churches and monasteries. In 1995, he received an award from the Russian government for his outstanding iconographic accomplishments.

At about this time, Fr Zinon associated himself with St Filaret’s Orthodox Institute in Moscow, whose director, Fr Georgii Kochetkov, was promoting liberalizing reforms in the Russian Orthodox Church, especially the use of Russian rather than Church Slavonic in the Divine Liturgy. Some conservatives, including monks from the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery, sharply criticized (and even physically attacked) Fr Georgii. Ensuing conflicts led Patriarch Aleksii II in 1997 to ban Fr Georgii from priestly service.[14] A year earlier, the bishop of the Pskov Diocese had placed Fr Zinon under a similar ban, after Fr Zinon had allowed a group of visiting Italian Catholics to celebrate the mass in the Mirozhskii Monastery and had received the eucharist from them.[15]

No longer attached to a monastery and penniless, Fr Zinon moved to Gverston’, a small village near the Estonian border, where he continued to paint icons and to receive visitors. Eventually making enough money to buy a piece of land, he designed and commissioned construction of a small stone chapel, in which he explored new ideas about liturgical space. However, because of the ecclesiastical ban, he could not celebrate the liturgy, even though he regarded immersion in the liturgy as central to his calling as a priest and an iconographer; and he was able to receive the eucharist only if another priest visited and presided. At the end of 2001, Patriarch Aleksii lifted the ban (as he had early in 2000 for Fr Georgii), although Fr Zinon’s ecclesiastical status remained unclear, insofar as he was no longer subject to a particular monastery or bishop.

In 2004–2005, Fr Zinon designed and painted the iconostasis for a small church on the site on which the charismatic priest and author Fr Aleksandr Men’, also associated with the more liberal wing of the Russian Orthodox Church, had been murdered in 1990. Fr Zinon’s next major commission came from Metropolitan Ilarion (Alfeev), at that time bishop of a Russian Orthodox diocese in Western Europe, to execute frescoes for the St Nicholas Cathedral in Vienna and for the iconostasis of its lower church (2006–2008). In 2009, Ilarion became head of the Church’s Department of External Relations and provided ecclesiastical cover for Fr Zinon (as he did for other members of the Church’s intelligentsia whose views had troubled some Church conservatives).[16] Their friendship goes back many years, and Fr Zinon has said that they have similar views about church art.[17]

In 2008, Fr Zinon moved to Mt Athos and painted icons for the Greek Monastery of Simonopetra. At about that time, a controversy arose in Pskov about icons that Fr Zinon, inspired by the twelfth-century iconography of Yaroslavl and Kiev, had painted in 1988 for the lower church of the Trinity Cathedral.[18] Because of excessive humidity and unstable temperatures in the cathedral, the icons required restoration. Rumors circulated that the bishop who had banned Fr Zinon from priestly service in 1996 was now seeking to destroy his icons. When the icons were again available for public view in 2009, Fr Zinon’s work could indeed no longer be recognized.[19]

Rumors were also circulating about Fr Zinon himself — that because of his alienation from the Russian Orthodox Church, he intended to remain on Athos or perhaps renounce the Russian Church and move back to his native Ukraine. However, after a brief period of indecision and wandering from one place to another, he returned to Russia in 2012, to design and execute the lower church of St Petersburg’s Feodorovskii Sobor, where, he has said, he had complete freedom to realize his architectural and iconographic vision. Since then, Fr Zinon has lived in seclusion in a provincial area several hours outside of Moscow. However, he continues to be active as an iconographer, while living in obedience to his monastic and priestly vows.

Iconography as Prayer

Fr Zinon is insistent that an icon is not a mere illustration of a holy figure, whether Christ, the Mother of God, or a particular saint. Rather, “an icon reveals. . . . It is a revelation of Christ’s kingdom, a revelation of the transfigured, divinized creation — indeed, of humanity itself as transfigured.”[20] Fr Zinon adds that this revelation is a revelation of God’s beauty, a beauty not determined by human standards (which would only reduce beauty to personal taste), but rather a beauty defined by the life of Christ, the One in whom God has become human. Fr Zinon believes that people develop a sense for this beauty as they participate in the life of the church, because it is, above all, in the church and its worship that God reveals himself and his beauty. Indeed, in the church’s celebration of the eucharist, believers receive Christ himself into their very bodies.[21] As the church shows forth God’s beauty, people learn to recognize it not only in the church but also in all of creation.[22]

Fr Zinon believes that icons, like music, architecture, and ritual, are essential to the church’s worship. An icon, he says, “truly lives only during the time of divine worship.” Icons witness to Christ’s incarnation and, therefore, “to the presence of Christ and the saints with us in the liturgy.”[23] Icons are a form of preaching, a confirmation of the church’s teachings about God. In addition, icons offer a way into prayer. They draw believers toward God; they learn to love God and to contemplate his perfect beauty. According to Fr Zinon, “an icon is for prayer, for inviting a prayerful posture, for assisting in prayerful unity with God. It makes a witness to God’s becoming human. . . . An icon is a school of prayer for those who contemplate it and pray before it.”[24]

Fr Zinon emphasizes that one does not pray to an icon but rather through it. He agrees with the traditional Orthodox understanding that a person prays to the one whom the icon depicts. However, this saint now belongs to a heavenly realm that transcends visual imagery. Fr Zinon therefore encourages people to allow the icon to dispose them to prayer but, then, to pray with their eyes closed, in contrast to popular practice. Also in contrast to many Russian Orthodox believers, Fr Zinon emphasizes that an icon does not possess miraculous properties. Rather, an icon is a witness to the God who has revealed himself in Christ. The point is not to admire the icon, but rather to love Christ.[25]

In order to make this witness to the truth that is God in Jesus Christ, the icon must be trustworthy. Fr Zinon therefore rejects iconography that, however popular, distorts the church’s teachings about God. He often cites the example of Synodal-era icons of the Trinity. These icons typically depict the Father as a bearded, elderly man looking down from heaven. However, Orthodox theology insists that God has become visible to humans only in the Son’s incarnation in Jesus Christ. Icons in which the Father appears as a human person fail to respect God’s transcendence. They are nothing less than false teaching.

Fr Zinon notes further that if iconography is to be true to church teaching, icons of the Trinity must not present Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as abstracted from history. Rather, a Trinity icon must clearly reference the biblical setting in which God revealed himself as “one essence in three persons.” Fr Zinon sees only four such instances: the three angels (in church tradition, representing Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) who visit Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 18); the baptism of Christ in the Jordan (when the Holy Spirit alights on him as a dove, and the Father speaks from heaven); Jesus’ transfiguration (when in the form of a cloud, the Holy Spirit overshadows him, and the Father again speaks from heaven); and the day of Pentecost (when the Holy Spirit descends as tongues of fire on the apostles, enabling them to declare the Father’s work in history, as it culminates in the Son’s incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection).[26]

Although icons printed in color on paper have become very popular (and inexpensive) in Russia – they are mass-produced by the Patriarchate – Fr Zinon rejects them.[27] In his view, they do not rightly witness to God’s beauty. At best, they “fool” us, imitating God’s beauty but not revealing it. An icon whose pigments have been made by hand from minerals and plants has natural, “authentic” colors that quiet the human spirit. They invite a person into prayer, whereas the artificial colors of printed icons are excessively bright and call attention to themselves. The worshipper ends up having to pray “against” and “in spite” of the icon, rather than with its assistance. Moreover, only natural elements, such as gold or silver, allow an icon to glow. It becomes a source of light, by which people experience the figure in the icon not simply as an object of their gaze but also as a subject that looks at and into them.[28]

Further, according to Fr Zinon, much of contemporary Russian iconography, even when canonical in technique and content, is problematic, because it stiffly copies ancient models. Fr Zinon insists that the icon painter is a creator. While remaining true to the church’s canons, he or she is offering a living response to God’s presence with humanity in this time and place. Fr Zinon notes that in the Russian Middle Ages, iconographers were guided by existing models but never simply copied them. Indeed, it was often the case that one viewed a great icon and then painted from memory.[29] This freedom, disciplined by the church’s spiritual practices of prayer and ascesis, is essential, if icons are to be living witnesses to the truth, rather than lifeless illustrations of saintly figures.

Fr Zinon identifies one other vital dimension to an icon’s trustworthiness. An icon is able to draw a believer into prayer only insofar as the icon itself is a creation of prayer. Fr Zinon notes that the Orthodox Church has traditionally regarded icon painting as a form of church service. Only someone deeply immersed in the church’s worship and life will rightly execute an icon: “Immersion in the life of the church is what is most important for an iconographer,” for an “icon grows out of the living experience of heaven that we receive in the liturgy.” Otherwise, an “icon remains superficial [and] unpersuasive.”[30] It obscures the church’s faith, rather than genuinely witnessing to it. Therefore, “an unchurched or unbelieving iconographer would be as monstrous a thing as an unbelieving priest. . . . Not just any artist is capable of being an iconographer. One may be a master craftsman, but if one does not live according to the values of the gospel, one should not paint icons.”[31] Indeed, Fr Zinon claims that just by looking at an icon, he can determine whether its author is living according to Christ’s commandments.

Fr Zinon as Monk, Priest, and Iconographer

Given these emphases, we would expect Fr Zinon’s own way of life to give us further insight into his understanding of iconography. How does he live out his religious commitments? Which particular spiritual practices sustain him and shape his iconographic vision? In recent years, Fr Zinon has been living in an isolated rural area, not far from one of Russia’s historic monasteries.[32] A high wall surrounds Fr Zinon’s property. Within are two modern houses — Fr Zinon’s and that of another monk, a builder of church furniture. A chapel, designed by Fr Zinon, stands between the houses and on the highest part of the property. The north windows of Fr Zinon’s house look out on a lush valley below. A large vegetable garden lies on the east side of the house.

Fr Zinon’s sensitivity to beauty is further evident in the architecture of his house and chapel. The two-story house is constructed of reddish-brown brick. Its warm color lies exposed on both the exterior and interior walls. Rooms are spacious and simply furnished; large windows provide for an abundance of natural light. Fr Zinon’s studio is on the east side. A photograph of Seraphim Tiapochkin hangs on the wall, as well as one of Fr Seraphim Rosenberg, a holy elder whom Fr Zinon served when he first entered the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery. The east wall of Fr Zinon’s dining area has icons of Christ and the Mother of God, toward which he prays at mealtimes. On the west wall, behind a long wooden table with benches, is a full-size, high-quality reproduction of Dali’s “Christ of St John of the Cross”; at meals, Fr Zinon sits right beneath it. The second story of the house consists of a large loft lined with shelves for his many books on art, theology, and liturgy.

Fr Zinon dresses in a simple black cassock. He maintains a strict ascetic regime, similar to that of Mt Athos. He eats no meat and typically arises at 3:00 a.m. Morning devotions consist of prayer and readings from the New Testament letters, the Gospels, and the Church Fathers, and can last as long as two hours. Fr Zinon especially values the writings of St Gregory the Theologian, who in the fourth century helped the church express more precisely Christ’s unique status as fully human and fully divine. After breakfast, Fr Zinon works in his studio. He says that as he paints, he especially likes listening to Bach, “the greatest composer of all time.”[33] The large noontime meal, which he himself prepares — he is an excellent cook — is followed by household chores and work in the garden. In the evening, he observes evening prayer and by 9:00 p.m. is in bed.

On Saturdays, Fr Zinon celebrates a version of the historic Latin liturgy of the Western, Roman Catholic Church; on Sundays and holy days, he uses a simplified version of the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, common to the Orthodox East. The furniture maker and any visitors attend, but there is no choir, and Fr Zinon does not sing any of the hymns (tropary) that developed over the centuries to honor particular saints or events in the life of Christ or Mary, and that typically embellish (and lengthen) Orthodox worship. Fr Zinon never gives a sermon; he regards preaching as instruction primarily for catechumens; therefore, it is not necessary for baptized believers, who instead gather to give thanks to God, especially by celebrating the eucharist.

The chapel, a small Byzantine-style basilica, with a Greek rather than Russian cross on top, is constructed of local stone. The exterior walls are finished with white stucco; inside, the smooth, dark stone lies exposed. The small, undecorated altar table is also of stone. As in early Christian churches, no iconostasis or barrier separates the altar area in the apse from the rest of the space. The church has only one icon, that of Christ the Pantocrator; it hangs just to the right of the opening into the apse.

These aspects of Fr Zinon’s personal life reflect his theological and liturgical commitments, which in turn inform his understanding of, and execution of, church art. He asks Christians today to return to the simplicity of the early Christian church. They are to witness to Christ and to invite people into intimate communion — theosis, “deification” — with him.[34] It is time, be believes, for the church to eliminate historical accretions to the Divine Liturgy, such as Byzantine court rituals, that obscure the original gospel proclamation. The simplified liturgical forms that Fr Zinon uses, the absence of a barrier in front of the altar area, and the singular visual focus within the liturgical space — the icon of the risen, ruling Christ — express his conviction that the Church will renew itself today only by recovering its ancient foundations. The first Christians experienced Christ as risen from the dead and immediately present to them. In response, they gathered for worship and reached out in love to one another and the world around them. Today, the Church’s arts should help people know this Christ and thereby enter into God’s transfiguring beauty.

Fr Zinon’s Understanding of the Church

Fr Zinon admires the Reformer Martin Luther for taking a stand against a medieval Catholic Church that had lost this guiding vision. Like Luther in his time, Fr Zinon today calls on members of the church to enter into the spirit of early Christianity by immersing themselves in the Scriptures. He appeals to the venerable Seraphim of Sarov, who said that “we should read Holy Scripture constantly, so that the mind ‘swims’ in the law of God. Then, one will always know what to do.”[35]

To be sure, in accord with traditional Orthodox thinking, Fr Zinon affirms that the Church’s authoritative teachings (especially from the early Church Fathers) will help believers interpret the Bible rightly. However, he resists the notion of many Russian Orthodox believers today, that one should not try to read the Bible on one’s own, or that one should passively submit to the directives of a priest or monk. Fr Zinon himself, in contrast to most monks, has no spiritual father yet understands himself to be true to the Church and its canons and dogmas. For him, Scripture and church tradition lead people to the one true spiritual authority, the risen Christ. Church authorities have spiritual authority only to the degree that they rightly represent the Church’s teachings about Christ.[36]

To enter fully into the life of Christ, however, people need not only Scripture and church dogma but also the liturgy. In the 1990s, when he associated closely with Fr Kochetkov, Fr Zinon seemed resigned to the argument that the Church would need to translate major parts of the liturgy from Church Slavonic into contemporary Russian, especially the hymns and New Testament readings appointed for each day. Otherwise, they would no longer draw believers into prayer but, instead, would become mere “museum pieces.”[37] Since then, however, Fr Zinon has argued that the Church is responsible to “lead people to the heights of knowing God, rather than to descend to the level of human ignorance.” Indeed, he says, “it would hardly occur to us to structure worship to suit minimal spiritual education, even if most people today do not understand the words of the hymnody or worship.”[38] Rather, the Church is responsible to help people know the faith, so that they practice it more deeply. He recalls how as a young believer, he could not yet understand Church Slavonic, but when he stepped into a church, its rhythms and intonations disposed him to pray. He soon wanted to learn Slavonic to appreciate its poetic beauty more fully.[39]

Fr Zinon believes that in a time such as ours, when language suffers from constant exaggeration and manipulation (as in advertising and the media), people suffer from information overload, Icons, therefore, may be better able than words alone to draw people to God. However, here too the Church must not condescend to popular taste. As we noted earlier, many Russian Orthodox believers are used to church art that is illustrative and sentimental. Fr Zinon disagrees with those priests who argue that canonical iconography demands too much of their parishioners. He is confident that when icons’ style and content are true to the Church’s historic faith, they quietly teach people how to pray, even when people do not immediately like or “understand” these icons.[40]

Fr Zinon’s confidence in the capacity of the liturgy and the Church’s arts to nurture people’s faith relates to his conviction that believers’ very lives can make an essential witness to God’s transfiguring beauty. When speaking of Seraphim Tiapochkin, whom he regularly visited until the elder’s death in 1982, Fr Zinon says, “It is hard to describe him. You had to be in his presence. There was just something about him.”[41] That “something” was Fr Seraphim’s radiant and selfless love. He demonstrated that “the best form of proclamation in our time [along with the liturgy and the Church’s arts] is the life of a person who embodies in himself the ideal of the gospel.”[42] Fr Zinon asks every believer to be an “artist” who creates beauty in his or her life, a beauty that reflects God’s beauty, in opposition to human selfishness and sin and their distortion of the world.[43]

A church in which every believer actively practiced the faith and created beauty would overcome traditional distinctions between monks and priests, on the one hand, and laypeople, on the other. To be sure, many believers have secular work, and monastics and members of the clergy will be able to devote more time to prayer and worship, and to engage in ascetical practices, such as fasting, more rigorously. Nevertheless, all Christians are called to live in moderation and to avoid temptations that divert them from God. Fr Zinon is critical of a tendency within Russian Orthodoxy, under the influence of medieval monasticism, to regard exhausting physical exertion — long worship services, severe fasts — as in itself a spiritual achievement. Instead, what is asked of believers, whether they are church hierarchs or simple parishioners, is to imitate Christ and his love. A true fast consists of repenting of sin and, then, concentrating expectantly on Christ, who is bringing about the transformation of the whole world.[44]

Fr Zinon notes that the Russian word for fast, post, expresses the idea of a soldier standing faithfully at his post, watching attentively. Each believer has a rightful and necessary place in the church and a commission to join in its witness. For Fr Zinon, following Christ is not a matter of fearing his judgment. Rather, Christians experience Christ as love, and they wish to love him, in return.[45] Nothing defines the church better than the gathered people’s common focus on Christ and the desire to serve him.

Because of the centrality of Christ to Christian faith, Christians gather especially to celebrate the eucharist. In accord with traditional Orthodox theology, Fr Zinon emphasizes that the priest represents Christ but does not replace him. Christ himself is present. He presides at the altar and invites believers to receive his body and blood. Church iconography, music, and architecture have only one task: to direct worshippers to the living Christ. Even Mary and the saints are worthy of veneration only because they point to him as the One who calls people into unity with himself and with one another.

Fr Zinon therefore wants people to be able to look into the altar area when the eucharist is celebrated, and to hear the priest’s words of thanksgiving. The people should be active participants in the church’s prayers, rather than passive spectators of clerical acts. He notes that in the early church, all of the members of a particular church community gathered for the liturgy and participated in the eucharist. In receiving the bread and wine, they were not solitary individuals; rather, they shared a meal. For a person not to have partaken would have been as strange as sitting with others at the dinner table and just watching. Fr Zinon is critical of parishes that celebrate the eucharist throughout the workweek, when few people can be present — a practice that he attributes to monastic influence on church life.[46] But he does call for people to gather for Vespers and Matins prior to celebration of the Divine Liturgy, in order to prepare themselves to receive the eucharist.[47]

In worshipping together, believers become a genuine community (obshchina, koinonia) of love and mutual service. Fr Zinon is critical of the contemporary tendency for people to come to church to fulfill personal spiritual needs, rather than to share a way of life together. Often, they do not know the names of their fellow parishioners or even notice who may be missing from the liturgy. Indeed, some believers complain that having other people around just distracts them from God. Fr Zinon wants to recover the sense of intimate, loving fellowship that characterized the first centuries of the Christian church. A parish that practiced this way of life together would be “church” in the fullest sense of the word — in Fr Zinon’s theological terminology, a “church of the Holy Spirit.”[48]

Fr Zinon understands baptism not as a rite that magically saves infants from “damnation” — a belief widespread in the Russian Church today — but rather as entry into life in Christ and with believers in a particular parish. Prior to their baptism, adults who are ignorant of church dogma and practice should undergo a lengthy process of catechization, as was the case in the early church. Children should be baptized only if their parents are practicing believers who are committed to raising them in the Christian faith. Further, children should be baptized only at an age (not earlier than three years, perhaps) at which they will be able to remember their baptism as a decisive moment of transition into a new life. Fr Zinon calls for returning to early church practices of fully immersing baptismal candidates into a pool of water, and of conducting baptisms in the context of the Divine Liturgy, with the congregation present. Such reforms would impress on the whole congregation that baptism calls us out of the world into a new way of life in a community of faith.[49]

Fr Zinon’s understanding of the church has implications beyond the individual parish. Fr Zinon believes that historic church divisions, especially between Catholics in the West and Orthodox in the East, do not undermine the church’s essential unity in Christ. After his bishop harshly criticized him for participating in the Catholic mass at the Mirozhskii Monastery, Fr Zinon replied that the Catholic and Orthodox churches recognize the validity of each other’s sacraments. Moreover, he noted, the space in which the mass had taken place had not yet been consecrated for Orthodox worship, and he cited instances in which the Russian Orthodox Church has made accommodations for Catholic visitors.[50] For Fr Zinon, the separation of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches is deeply painful, and he wishes to contribute to their reconciliation.[51]

Here, however, Fr Zinon’s own way of life demonstrates the difficulty of realizing his vision of intimate Christian community. While his creative work and inspiring personality have always drawn others to him, he confesses to never having had a “genuine friend,” others with whom he could deeply share his life.[52] Some critics have said that at the Pskov-Pecherskii Monastery he remained aloof both from his superiors and from ordinary believers. Further, when he was in charge of the Mirozhskii Monastery, he acted on his own authority, not under direct Church supervision. These critics accuse him of elitism — as in conducting candlelight services not open to outsiders, or in painting icons that lack human warmth. Some regard the figures depicted especially in his more recent icons as distant and uninviting.[53] For his part, Fr Zinon has frequently criticized the Russian Church for catering to the tastes of its uneducated, superstitious babushki. Icons, in his view, should indeed point people beyond this world.

Surely, the pain that the Russian Church has inflicted on Fr Zinon has contributed to his reputation as a loner and to an existence on the margins of the Church. When he receives visitors today, he gladly drives them to the nearby monastery, but he himself remains in the car, while they go onto the grounds. He wants to avoid curious questions or the accusing looks of other monastics. Fr Zinon believes that genuine Christian community is virtually impossible in the Russian Church today — and perhaps anywhere in the modern world — because of people’s deeply ingrained individualism. But the problem is also with the Church itself. Church leaders resist cultivating trusting community among parishioners and, instead, seek institutional power and hierarchical control.

Despite his frustrations with the institutional Church, Fr Zinon refuses to renounce his vows or to abandon church life. He does not want or expect Christians to be large in number or influential. He notes that Christ called his followers “a little flock,” “sheep among wolves.” Few people, even within the church, are truly prepared to follow Christ. Fr Zinon is nevertheless confident that those who do commit themselves to discipleship are “salt of the earth.” They help preserve the world as a whole from “spoiling.”[54]

Iconography in the Post-Communist Church

Fr Zinon believes that in every era the church’s arts reflect the church’s spiritual condition. After the first centuries of persecution, when the church was finally able to construct church buildings, its art, as in the famous sixth-century mosaics of Ravenna, expressed believers’ joy and delight in the beauty that Christ had brought into the world. The influence of Byzantium in early medieval Russian iconography testified to a church that did not yet see itself as distinctively Russian but rather as a representation of the church universal. Fr Zinon draws further inferences from the twelfth-century Novgorodian icon of the Savior of the “Zlatye vlasy” (Golden Hair), whose huge eyes meet the worshipper no matter where he or she stands in the church. The icon reflects a church that still called every member into active participation in worship. By contrast, Dionysius’ icons in the fifteenth century suggest a fundamental change in attitude. They are softer in color and finer in draftsmanship; one can make their figures out only from a few feet away, as though the church were no longer concerned that all could easily see, hear, and participate in the church’s worship. Indeed, as Fr Zinon notes, priests at that time began reciting the eucharistic prayers quietly behind a tall and solid iconostasis.

The Synodal period that followed Peter the Great’s abolishment of the Patriarchate in the early eighteenth century corresponded to further changes in church life. Icons in the style of Andrei Rublev were deemed “Old Believer,” at a time when Old Belief was illegal and regarded as heretical. The Holy Synod, under control of the tsar, dictated that Russian church arts be oriented by Italian tastes, even as the tsar was commissioning Italian architects to design monumental buildings and churches for St Petersburg and elsewhere. Similarly, the circumstances of the Church in the Soviet era had implications for the Church’s arts. The regime’s confiscation of icons — placing them in museums, selling them abroad, or simply destroying them — was part of its program for eradicating religion.

Fr Zinon believes that the general state of Russian iconography today reflects the dire situation of a post-communist Church that instead of realizing its creative potential, submits itself to state interests, as it did during the Synodal period. The Church’s aesthetic is in crisis. Simple items necessary for the Church’s liturgical life, such as candleholders, railings, and church furniture, were once crafted by hand. They had life; they bore marks of creativity. Today, a Church that values control and conformity mass-produces them with machinery, and they are of poor quality. Similarly, new churches are constructed according to a handful of fixed architectural models. Icons, both printed and painted, are reduced to consumer products. People easily acquire dozens of inexpensive icons whose colors quickly fade.[55] In contrast, genuine icons are holy by virtue of the iconographer praying them into being. Once the iconographer has written on the icon the name of the saint to whom it is dedicated, the icon is complete. Today, however, people want a priest to “consecrate” their mass-produced icons, as though the icons thereby attain a holy status that they otherwise lack.[56]

The slavish mentality of the Synodal era is evident more generally in the Church’s celebration of worship and sacraments. Soon after the fall of communism, Fr Zinon wrote, “We now have the possibility of restoring to the Church the understanding of the sacraments that we have inherited from the early Church Fathers. We have the possibility of returning to the genuine foundations of church life. But on the basis of the monasteries and churches that have been reopened so far, one has to conclude the very opposite: We are restoring the same Synodal forms of church life that failed to prove themselves historically and that led to the catastrophe of 1917.”[57]

Fr Zinon sees his iconography as setting forth an alternative vision of church life. Even though the current condition of the Russian Church discourages him, he believes that reform is inevitable, and that changes at the bottom may stimulate wider efforts.[58] Therefore, what happens at the level of the parish is of great importance to him. If parishes become loving communities in which every member knows him- or herself to be valued and in which he or she is able to participate actively in worship and loving service to others, a genuine alternative to the present stagnant church situation may develop. The Church’s arts should point people toward this possibility.

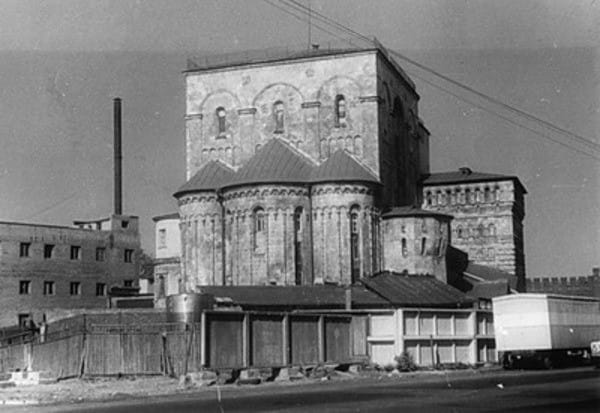

In 2012–13, Fr Zinon had the opportunity to realize his theological and artistic vision in St Petersburg’s Feodorovskii Sobor. The cathedral was constructed in the early twentieth century to coincide with celebration of the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Romanov dynasty in 1613.[59] In 1932, the Bolsheviks closed the church, removed its domes and marble cladding, attached work sheds, and turned the complex into a milk factory. Although immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union, government authorities promised to return the building to the Church, various bureaucratic obstacles delayed transfer of title until 2005. In the meantime, the parish built a small wooden chapel on the grounds of the cathedral; restoration of the cathedral itself was beyond its financial means. However, in 2007, in anticipation of the cathedral’s centenary, government officials and business leaders decided to raise the needed funds.

Work focused initially on the exterior of the building and, within, on the main, upper church. The goal was to restore as much as possible their original appearance, based on surviving architectural plans and photographs. The smaller, lower church was another question, however. With the outbreak of war in 1914 and the revolutionary years that followed, work on the lower church had never been completed. Nor did architectural plans or sketches lie in archives. Only a short notice in the records of the original building committee left a hint of its intentions, namely, that the design be based on ancient church architecture. Now, a hundred years later, this idea resonated with the parish and its head priest, Fr Aleksandr Sorokin. For a brief period after the return of the cathedral and prior to its restoration, they had celebrated worship in the upper church, while it was still an open, unfinished space. The experience had been surprisingly positive. The absence of an iconostasis had focused the parish on the altar area, the eucharist, and one another’s presence.

Fr Aleksandr had long known Fr Zinon and admired his work. Having seen the simple, stone chapel in Gverston’, in which Fr Zinon had installed a low stone barrier rather than a solid iconostasis, Fr Aleksandr was convinced that he was the right person to design the lower church. When Fr Aleksandr first approached him in 2008, Fr Zinon was on Athos and had no interest in returning to Russia. By 2012, however, Fr Aleksandr had succeeded in winning him over. In order to complete the project by the anniversary the following year, Fr Zinon went furiously to work, with the full support of Fr Aleksandr and the project managers.

While the upper church has a traditional, multistoried iconostasis that reaches to the ceiling, the lower church has only a low barrier. Its natural stone and metals give warmth to the space. For Fr Zinon, the purpose of this barrier is primarily practical, namely, to keep the altar area free for the priests to move about. To the right and left of the altar area are icons of Christ the Savior and Mary the Theotokos, the central foci in every Orthodox church. Here, however, they are larger than life-size, and they “stand” to the side, leaving worshippers an unobstructed view of the altar.

Smaller icons, many of them devoted to great ascetics of the early church, hang on the large, square pillars that support the upper church. The arrangement of a typical Orthodox church implicitly emphasizes the saints’ role as intercessors between the people and God. They peer at us from the iconostasis, which mediates between the nave and the altar area. In Zinon’s lower church, in contrast, the saints in the icons seem to gather with the people to form one congregation. The dead and the living, as it were, lift up their praise and thanksgiving to God together. The fact that members of the parish financed these icons further adds to one’s sense that these saints are part of the worshipping community.

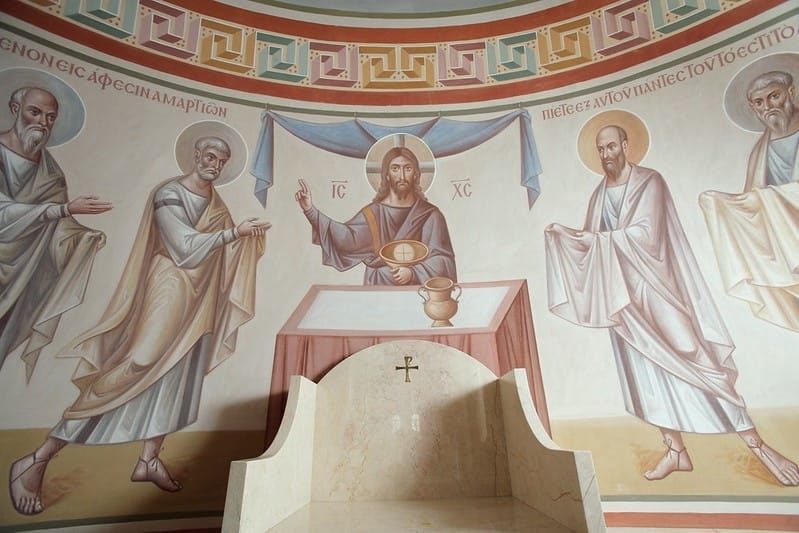

As worshippers look into the central apse, they see a small and undecorated altar-table. In a typical Orthodox church, a large, ornate tabernacle stands on the altar-table. Fr Zinon’s church draws one’s attention, instead, to a large fresco on the wall of the apse behind the altar-table. Christ is depicted as seated at a simple wooden table. He lifts the first two fingers of his right hand, the gesture in antiquity for a teacher; in his left hand, he holds a bowl with a large white discus that symbolizes Christ as the bread of life. To his left and right stand apostles and evangelists in a long row. Each figure leans in toward him, with outstretched hands, as though to receive the eucharist directly from him. While most of the figures gaze at Christ, the Evangelist Luke looks directly at the worshippers, as though to draw them too into the sacred events into which the eucharist calls us to participate. Above the apostles and evangelists are Jesus’ words to his disciples at his Last Supper: “Take eat. Drink all of you.” Fr Zinon has lettered them in Greek, the original language of the gospel.

Fr Zinon asserts that the design of the lower church fully realizes what makes the church “the church.” The space invites people to see themselves as the new people of God. Like the apostles and evangelists, they look toward Christ and confess him as Lord. Outside the altar area and to the side is a large baptismal pool, deep enough for immersion of an adult. It is in the shape of a cross, symbolizing that a person joins this new people by dying to sin (the waters drown) and becoming a new being in Christ (the waters give life).

Fr Zinon has carefully designed the space so that all of its elements relate harmoniously and have symbolic value. The frescoes in the north apse, where the priest prepares the eucharistic elements, are devoted to three Old Testament figures — Abraham, Moses, and Melchizedek — whom early Christians regarded as prototypes of Christ as the incarnate God and as the eucharistic sacrifice. In the south apse, where priestly garments and liturgical instruments are stored, the frescoes depict scenes from the Book of Acts, which records the early church’s missionary activity. Fr Zinon notes that he intentionally avoided excessive ornamentation and illustration that would tire the eyes and divert them from the icon of Christ in the central apse.

The iconographic style that Fr Zinon has employed in the lower church defies easy categorization. As we have seen, his work over the years has found inspiration in ever earlier periods of time — from Vasnetsov to Rublev, to eleventh-century Russia, to Byzantium, and to Ravenna. Some of his iconography in the Feodorovskii Sobor reaches back even further, to echo the early Christian art of the Roman catacombs. Fr Zinon acknowledges that each style reflects a particular social, ecclesial world that is no longer accessible to us. If one tries to paint icons in just one of these styles or another, the result will be an artificial stylization, rather than a living witness to Christ. The best solution, he argues, is a synthesis all of these styles, along with that of the Synodal period, to create something fresh that speaks to people today.

Fr Zinon believes that the days of Christian dominance in Western societies are over. There will be no new Christian tsar in Russia, nor should there be. The church is not the church by virtue of social prestige or political influence. Here, again, we have Fr Zinon’s conviction that true followers of Christ will always be a tiny flock. But their voice, however small and weak, will offer creative possibilities that the world needs. Their distinctive way of life as a community of loving service will show a way beyond the demoralization and fragmentation that so often characterize modern societies.

The Politics of Freedom

Leitmotifs of Fr Zinon’s life have been freedom and creativity. As a young art student, he sought the freedom to paint icons, rather than Social Realist scenes. As a beginning icon painter, he claimed the freedom to move away from the dominant Synodal style and explore earlier periods of Russian and Byzantine iconography. Later, when appointed head of the Mirozhskii Monastery, he had the freedom to determine the rule of life by which his community would live. Even the years under ecclesiastical ban, however difficult personally, further expanded Fr Zinon’s freedom to pursue his own creative path.[60]

In his reminiscences of Seraphim Tiapochkin, Fr Zinon remarks on the holy elder’s remarkable sense of spiritual freedom. Due to be released after ten years in a Soviet prison camp, the commandant asked Fr Seraphim what he planned to do next. Without hesitation, he replied, “I am a priest. I will serve the liturgy.” In that case,” said the commandant, “I am going to have you sit for another five years.” When Fr Seraphim was finally released, he did indeed return immediately to priestly service. The years of suffering had only strengthened his resolve. He knew that he was free inside of himself, no matter what the state might still do to him.[61] Similarly, Fr Zinon’s suffering at the hands of the Church has deepened his creative freedom. He has taken artistic risks, and they have made his iconographic work a remarkable contrast to the dull conformity that characterizes so much of Russian church art today.

Fr Zinon notes that Seraphim Tiapochkin never spoke about politics and said little about his years in the gulag. His focus was elsewhere. He lived with a steady sense of God’s merciful transfiguration of all of reality. Fr Seraphim wanted people to see God’s beauty, even in the midst of their sometimes desperate life circumstances. Fr Zinon, too, has little to say about politics. He is not a proponent of a monarchy headed by a Christian ruler, an idea dear to some Russian Orthodox believers.[62] But neither does he regard himself as a proponent of democracy, despite his association with the more liberal wing of the Russian Orthodox Church. When pressed, he simply replies that government is necessary because of human sin. The state should care for the wellbeing of its citizens (he mentions prohibiting pornography, in particular), but it cannot cultivate Christian virtues of love.[63]

Nevertheless, Fr Zinon’s vision of the church does resonate with some Western democratic ideals. Every member of the church should actively participate in the community’s life. The church is defined by loving service, not by a hierarchy of power. The parish is a place of freedom that gives people space for creativity. However, in contrast to secular liberalism, Fr Zinon believes that freedom must be disciplined by a focus on God, rather than on the self and its desires. Creativity is not for its own sake. Fr Zinon respects the Church’s canons, because they define for him what true freedom is about.

Fr Zinon therefore prefers to call his social vision “theocratic.”[64] He does not mean a political order in which the Church determines the nation’s laws. Rather, he is referring to a Christian community that lives according to God’s will as set forth in Scripture and church tradition. The world will have its own rules and regulations, and Christians may support or oppose particular government policies. But the purpose of the church is to direct people’s attention beyond this world to Christ, who is the ultimate source of their life. Here, for Fr Zinon, is where real freedom lies.[65]

John P. Burgess is professor of theology at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Photos of Fr Zinon’s work are by permission of the Feodorovskii Sobor.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

[1] See Matthew Lee Miller, “Eastern Christianity in the Twin Cities: The Churches of Minneapolis and St Paul, 1989–2014,” Modern Greek Studies Yearbook 30/31 (2014/2015): 109.

[2] See Aidan Hart, “Archimandrite Zenon (Theodor): His Life and Work,” Orthodox Arts Journal (Nov. 6, 2014), orthodoxartsjournal.org; and Lidia Chakovskaya, “Contemporary Russian Art—Between Tradition and Modernity,” in Orthodox Paradoxes: Heterogeneities and Complexities in Contemporary Russian Orthodoxy, ed. Katya Tolstaya (Boston: Brill, 2014), 318–337.

[3] Russian art historian Irina Iazykova has noted the importance of interpreting Fr Zinon’s work with attention to his theological ideas. See Irina Iazykova, So-tvorenie obraza: bogoslovie ikony (Moscow: BBI, 2012), 274–277; and Irina Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant: The Underground Struggle to Save Russian Iconography, trans. Paul Grenier (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2010), 135–140.

[4] I elaborate on this point in “A Visit to Fr. Zinon,” First Things (Jan. 2024): 47‒52.

[5] Much of the following biographical information is compiled from the author’s personal interviews with Fr Zinon in 2012 and 2019. I also draw from Vasilii Tolstunov and Viktoria and Mikhail Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam drevnikh,” Russkaia Gazeta (May 14, 2009), rg.ru; Valentin Konstantinovich Kazerskii, “Kogda slovo stalo Plot’iu” (March 1, 2015), damian.ru; “Zinon (Teodor),” in academic2.ru; and Nikolai Chernyshev and I.K. Iazykova, “Zinon,” in Pravoslavnaia entsiklopediia, vol. 20 (2014): 181–183, pravenc.ru. All translations from Russian sources are my own.

[6] “Teodor, Michail Nikolaevich,” in ru.wikipedia.org.

[7] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[8] Archimandrit Zinon Teodor, Besedy ikonopitsa (St Petersburg: Bibliopolis, 2017), 89. This book has been through several editions; a good part of the material goes back to Archimandrite Zinon, “Ikona v liturgicheskom vozrozhdenii,” in Pamiatniki Otechestva 26/27 (1992), 57–63.

[9] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[10] Timur Shchukin, “Ty monach: zhivi odni,” Voda zhivaia (April 2012), in Besedy, 141.

[11] For the significance of holy eldership in Russia, see Irina Paert, Spiritual Elders: Charisma and Tradition in Russian Orthodoxy (DeKalb: Northern Illinois Univ. Press, 2010).

[12] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[13] See Yazykova, Hidden and Triumphant, 135.

[14] For a recounting of these events, see Wallace Daniel, The Orthodox Church and Civil Society in Russia (College Station: Texas A&M Press, 2006).

[15] See Aleksandr Shchipkov, “The Scandal of Archimandrite Zenon (Teodor),” Keston News Service (July 21, 1999).

[16] In 2022, Ilarion was removed from his position and appointed to head the Church’s Diocese of Hungary-Budapest.

[17] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[18] For reproductions of the original icons, see Hart, “Archimandrite Zenon.”

[19] See “Zinon,” Pravoslavnaia entsiklopediia; and “Lenta novosty,” Portal Credo.ru (Jan. 21, 2009).

[20] Zinon, Besedy, 15.

[21] Aleksandr Sorokin, “Svet i teni tserkovnoi zhizni,” Zhivaia voda (Dec. 2010), in Besedy, 125.

[22] Zinon, Besedy, 42.

[23] Kazerskii, “Kogda slovo.”

[24] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[25] Sorokin, “Svet i teni,” 127–128.

[26] Zinon, Besedy, 18. For an explanation of the Pentecost icon, see John Baggley, Festival Icons for the Christian Year (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000), 141.

[27] Fr Zinon is referring to the Church’s factory Sofrino.

[28] Zinon, Besedy, 25–26.

[29] Zinon, Besedy, 30, 39.

[30] Zinon, Besedy, 123, 16.

[31] Sorokin, “Svet i teni,” 138–139.

[32] These observations are based on the author’s visit to Fr Zinon’s home in August 2019.

[33] See Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[34] Zinon, Besedy, 116.

[35] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[36] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[37] Zinon, Besedy, 91.

[38] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[39] Zinon, Besedy, 89, 91; see also Viktor Mamontov, “O liturgicheskom vozrozhdenii,” religion.wikireading.ru.

[40] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[41] See Fr Zinon’s comments in Sofronii Makritskii, Neugasimii svet liubvy (Moscow: Blagochestie, 2017), 293.

[42] Zinon, Besedy, 45

[43] Zinon, Besedy, 42.

[44] Zinon, Besedy, 57, 62–65.

[45] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[46] Mamontov, “O liturgicheskom.”

[47] Zinon, Besedy, 84. Fr Zinon’s understanding of the eucharist draws heavily from the work of Fr Alexander Schmemann. See Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1987).

[48] Zinon, Besedy, 102. Fr Zinon acknowledges here his debt to Fr Nicholas Afanasiev. See Nicholas Afanasiev, The Church of the Holy Spirit, trans. Vitaly Permiakov (Notre Dame: Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 2007).

[49] See Zinon, Besedy, 69; and Mamontov, “O liturgicheskom.”

[50] Shchipkov, “Scandal.”

[51] Zinon, Besedy, 107.

[52] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[53] Svetlana Rzhanitsyna, “Tvorchestvo o. Zinona,” Moskovskaia ikonopis’ kontsa XX veka, rsvetal.narod.ru/dipl5.htm.

[54] See Kazerskii, “Kogda slovo”; Mamontov, “O liturgicheskom”; and Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[55] Sorokin, “Svet i teni,” 128–133.

[56] Zinon, Besedy, 25.

[57] Zinon, Besedy, 102.

[58] Zinon, Besedy, 103–104.

[59] The following draws from Anastasie, ed. Aleksandr Sorokin and Aleksandr Zimin (St. Petersburg: Zimina, 2013). The volume includes essays by Fr Aleksandr Sorokin, Fr Zinon, and Irina Iazykova.

[60] See Aleksandr Sorokin, “Istoria,” in Anastasie, 12, 15.

[61] Zinon, Besedy, 45.

[62] Zinon Teodor, “Kosmos,” in Anastasie, 61.

[63] Shchukin, “Ty monach,” 147–148.

[64] Tolstunov and Serdiukovy, “Po retseptam.”

[65] See Irina Papkova, The Orthodox Church and Russian Politics (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2011); and John P. Burgess, Holy Rus’: The Rebirth of Orthodoxy in the New Russia (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2017).

This is a wonderful article. There is so much to think about. Thank you.

I visited Feodorovskii Sobor with Philip Davydov and Olga Shalamova. In the upper church was a depiction of the original iconostasis in which the image of the Trinity at the top shows Christ, then God the Father as an old man. You quote Fr Zenon as saying, “icons of the Trinity must not present Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as abstracted from history”. While the reconstructed iconostasis replicates all the original icons faithfully, the Trinity icon at the top has been replaced with one more closely resembling Rublev’s version.

Thank you for your appreciative words and for the observations about the upper church iconostasis.

Reading this article caused such a depth of feeling in me that I could not read all of it at once!

So much gratitude!

Amen

Thank you for your interest. Fr Zinon has indeed a moving vision of life before God.

The iconography reminiscent to me not just of Ravenna but to that of Photis Kontoglou.

It would be interesting to investigate whether Fr Zinon knows of his work.