Similar Posts

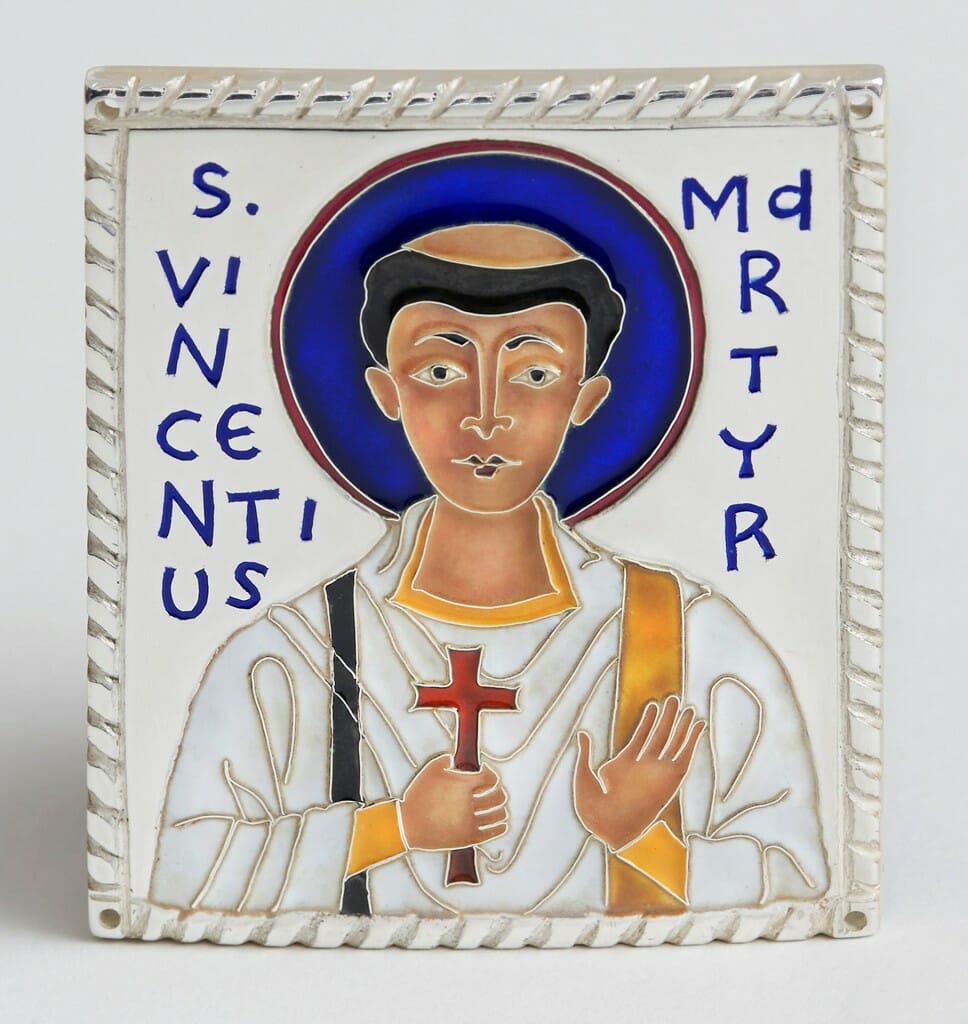

Editor’s note: This article continues Aidan Hart’s recent article about a reliquary for Saint Vincent of Zaragoza and details Christabel Anderson’s process for making the cloisonnée icon.

Cloisonné enamel icon plaque of Saint Vincent of Zaragoza, Deacon and Martyr, by Christabel Anderson, January 2015. Designed by Aidan Hart. Fine silver champlevé and cloisonné with vitreous enamel, 5.3 x 6.4cm.

This article contains a background to the history and technique of cloisonné enamel and a description of the processes used in making the cloisonné enamel icon plaque of Saint Vincent of Zaragoza for a reliquary box designed by Aidan Hart for Saint Mary Magdalene Russian Orthodox Church in Madrid, Spain.

Background to the Project:

Saint Mary Magdalene Russian Orthodox Church was given a relic of Saint Vincent, the protomartyr of Spain, and commissioned a reliquary to be made by Aidan Hart to hold it. Aidan designed the reliquary, hand carved the silver and set the stones with which the box is adorned. The wooden reliquary box was made by Dylan Hartley and I was asked to make the cloisonné enamel icon of Saint Vincent.

Saint Vincent of Zaragoza:

Saint Vincent was a deacon who was imprisoned in Valencia for his Christian faith and subsequently martyred there under the Emperor Diocletian in AD 304. His feast day is celebrated by the Orthodox Church on the 11th (24th) of November. Saint Vincent was born in the 3rd century in Huesca in north-eastern Spain and lived in Zaragoza (Saragossa) where he served as a deacon under Valerius of Zaragoza, the city’s Bishop. The earliest written account of Saint Vincent’s martyrdom was by the poet Prudentius, writer of a series of lyric poems called Peristephanon or ‘Crowns of Martyrdom’. Prudentius described how the Saint was brought to trial and that his fearless testimony resulted in him being tortured and martyred. According to his legend, ravens protected Saint Vincent’s body until his followers could recover it and take him to be buried. His grave, located at what is now known as Cape Saint Vincent, continued to be guarded by flocks of ravens. In the time of Muslim rule, an Arab geographer, cartographer and traveller known as Al-Idrisi (1099–1165/6) described the presence of these guarding ravens and consequently named this place the ‘Church of the Raven’ (‘Kanīsah al-Ghurāb’ or كنيسة الغراب).

Inspirations and Research:

As usual in making any icon I first learned as much as possible about the life of the Saint and sought out traditional iconographic representations of him. I find this essential in all my work as part of understanding the personalities involved and developing a sense of connection with them. During the research process I was particularly drawn to a remarkable fresco of Saint Vincent from the 11th century, which is located in the Santuario Madonna della Neve, previously the Chiesa di San Vincenzo, in Cucciago, a small town in the province of Como, just north of Milan in Italy. I kept this icon on my desk throughout the making of the enamel so that it could be seen at all times while working and also included as part of my daily prayers.

Icon of Saint Vincent of Zaragoza, 11th century painting from the Chiesa di San Vincenzo, Cucciago, Italy. Source: https://forallsaints.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/vincent-of-saragossa.gif

I also studied to understand further about the style, forms and folds of his vestments and found an early mosaic from Ravenna, with depictions of Saints Polycarp, Vincent, Pancras and Chrysogonus appositely robed. Their names can be discerned in the Latin text above their golden halos.

Mosaic depicting Saints Polycarp, Vincent, Pancras and Chrysogonus, in the nave of the 6th century Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Source: http://www.marysrosaries.com/collaboration/images/d/d0/Saints_Polycarp_-_Vincent_-_Pancras_and_Chrysogonus.jpg

About Cloisonné:

Cloisonné is an ancient technique used for the decoration of metal objects. The term cloisonné derives from the French word cloison, meaning ‘partition’, or ‘cell’. In this technique, small compartments or chambers are created through the application of thin walls formed out of wire, usually in silver or gold. These are then filled with enamel, or inlaid with cut glass, gemstones or other materials such as glass paste, which was often used in ancient Egypt. In the early part of its history, cloisonné tended to be made with thicker cloison walls. However, from about the 8th century, Byzantine techniques involved the use of thinner wires in order that finer and more complex pictorial images could be fashioned.

There are two main techniques in Byzantine and European cloisonné enamel, which are the earlier vollschmelz (‘full melt’) technique in which a gold base plate is entirely covered with enamel. The edges of the plate are turned up, forming a reservoir, and then gold wires are formed and soldered in place to create the cloisons. Enamel is then applied to the entire reservoir or surface of the metal. The second technique, developed later, is the senkschmelz (‘sunk melt’) technique, in which the parts of the base plate to hold the design are hammered into a recess, leaving a surrounding gold background. The cloisonné wire and enamels are then added in the usual manner. In later European enamelling champlevé came to be favoured over cloisonné as is demonstrated by the many enamels produced in the workshops of Limoges, France.

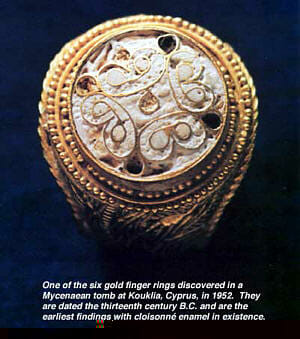

The earliest surviving examples of cloisonné are from Cyprus, these are gold rings which were discovered in 1952 in graves dating to the 13th century BC.

Gold and cloisonné ring, Cyprus, 13th century BC. source: http://www.ganoksin.com/borisat/nenam/nenamart/gom-clipart/Cyprus5.jpg

Cloisonné objects have been produced by many cultures including Ancient Egyptian, Sumerian, Byzantine, Chinese and Japanese. Cloisonné and champlevé enamel have also been made in the British Isles since pre-Christian times and continuing throughout the Christian period. A well known Anglo Saxon example would be the Alfred Jewel, made in the latter part of the 9th century of filigree gold, enclosing a polished tear-shaped piece of transparent colourless quartz rock crystal, underneath which is set a cloisonné enamel plaque believed to be a depiction of Christ with ecclesiastical symbols:

The Alfred Jewel, late 9th century, England, 2 ½ inches (6.4cm) in length. Filigree gold, quartz rock crystal and cloisonné enamel. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, gallery 35 Source: http://www.applefm.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/The-Alfred-Jewel-2-e1421432834638.jpg

Numerous outstanding examples of the art of cloisonné enamel were produced in Constantinople. The entire upper third of the Pala d’Oro (‘Golden Cloth’) altarpiece, now in the Basilica di San Marco in Venice, is universally considered to be one of the most extraordinary and accomplished works of Byzantine craftsmanship. It originally came from one of the three churches of the Monastery of Christ Pantocrator in Constantinople and was made in the early 1100s:

The Archangel Michael, detail from the Pala d’Oro in Venice. Cloisonné and champlevé enamel, gold and gemstones.

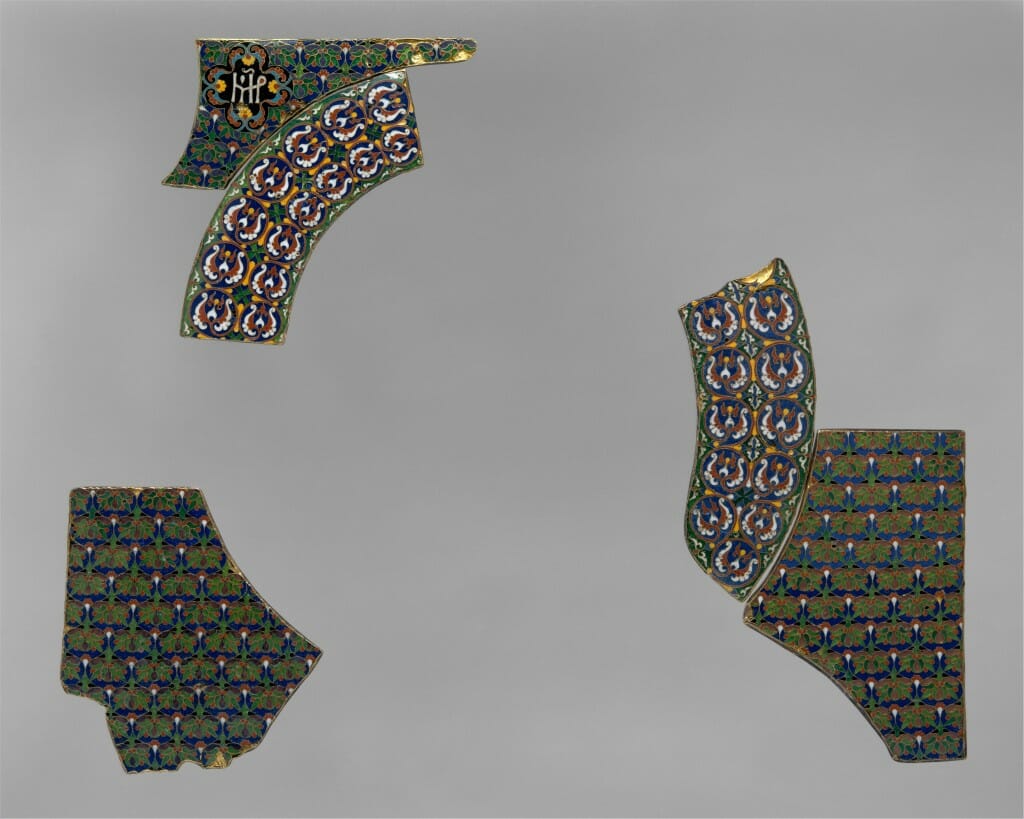

Other examples from Constantinople include icon roundels and revetments, generally used to protect and adorn some of the most precious relics of the Church:

Panels from a Byzantine icon cover (or riza, επένδυση) from an icon of the Most Holy Theotokos Hagiosoritissa, or ‘Virgin of the Hagia Soros’ (Holy Reliquary). Made in Constantinople, c. 1100. Cloisonné enamel, gold and copper in the vollschmelz technique. Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art, New York, gallery 303. Source: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/464514

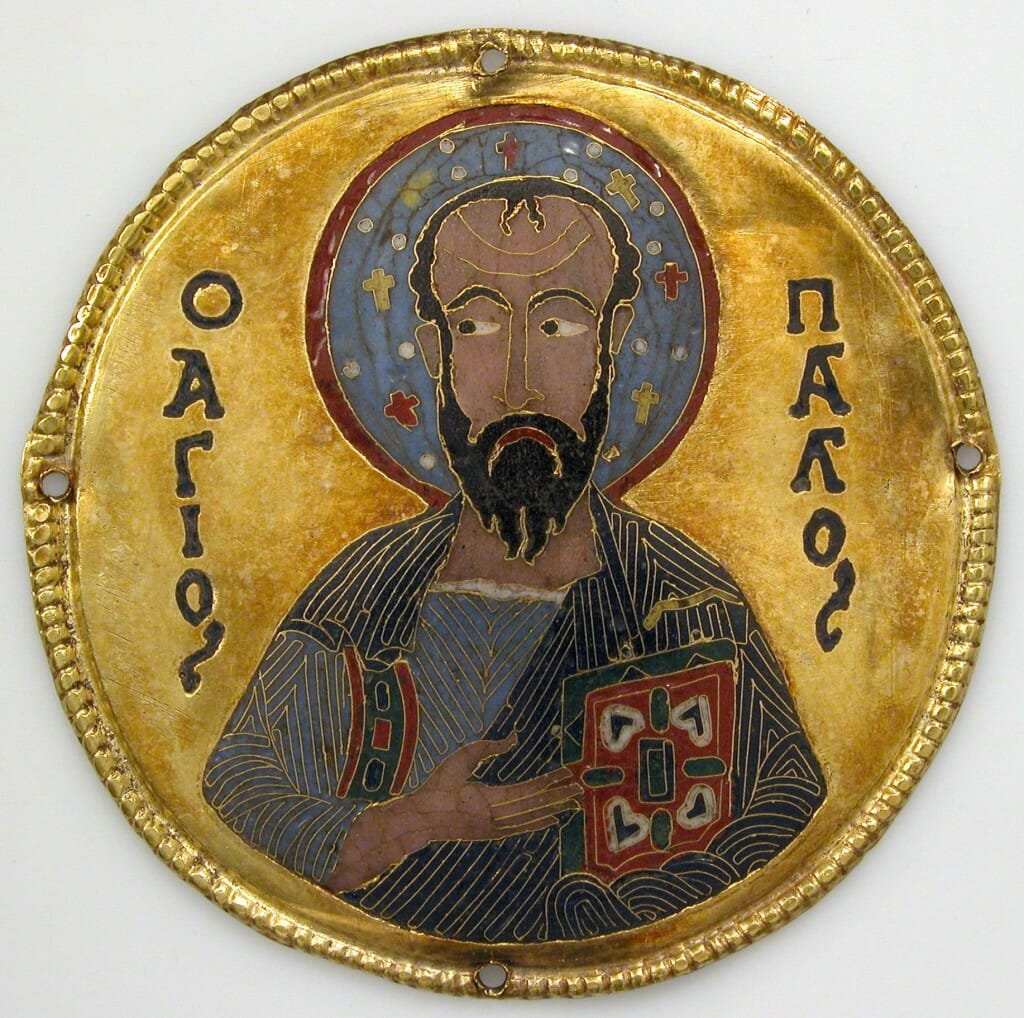

Byzantine medallion icon of Saint Paul from an Icon Frame. Made in Constantinople, c. 1100. Cloisonné enamel and gold made using the senkschmelz (‘sunk melt’) technique. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gallery 303. Source: http://images.metmuseum.org/CRDImages/md/original/sf17-190-673s1.jpg

The practice of cloisonné enamelling has also been employed extensively in Russia, which has produced countless extraordinarily fine examples of this art form:

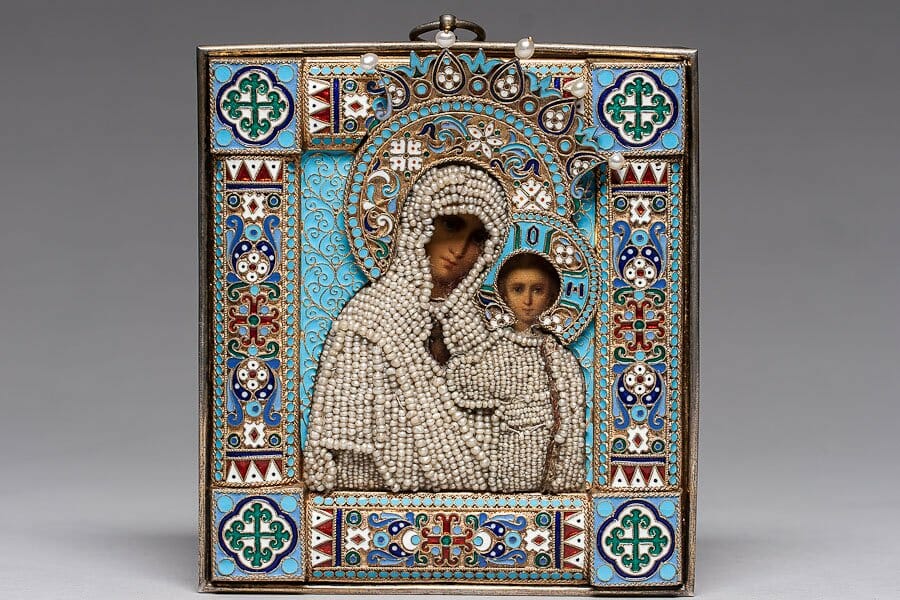

Silver-gilt and cloisonné enamel icon of the Kazan Mother of God, c.1900, Moscow. The icon itself was painted in oil on a zinc plate and the figures of Mother of God and Christ Child are covered with pearls. The remaining surface comprises detailed patterns in cloisonné enamel. Marked P. Ovchinnikov with the imperial warrant and 84 standard (875/1000 – indicating its fineness) silver. Size: 4 ¾ x 4 ¼ inches (12 x 11cm). Source: http://p2.la-img.com/1341/29951/11637047_1_l.jpg

Symbolism & Meaning:

There is minimal written material that I have thus far discovered on this subject so here I am drawing on personal experience and careful consideration more than textual sources. Reflecting upon the meaning of enamel in the context of the liturgical arts of the Holy Orthodox Church, and in particular cloisonné enamel, something of the spirit of monasticism in both the making processes and finished result can be discerned. Every aspect of the process of creating a cloisonné enamel icon requires the iconographer to be highly meticulous and contemplative, requiring much focused silent concentration and devotion. Each cloison or cell is part of the whole and yet solitary (‘monos’), communicating its own special presence and, for me, evoking patristic wisdom such as ‘Go, sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything’ (Saint Moses the Black), or ‘Go, eat, drink, sleep, do no work, only do not leave your cell’ (Saint Arsenius the Great). Saint Isaac the Syrian said ‘Be the friend of all, but in your spirit remain alone’ and ‘Be a partaker of the sufferings of all, but keep your body distant from all’. The cloisonné enamels of the Orthodox Church exemplify this combination of participation and aloneness.

The enamel itself is light bearing and highly durable in nature, evoking the incorruptibility of the Heavenly Kingdom. Cells filled with purified luminous glass on a bed of shining precious metal communicate the bright Uncreated Light of eternity in a way that few other mediums can rival. Processes such as the purification by fire and acid of the precious metals, the grinding and washing of the enamels and their firing at high temperatures altering their state, mirrors our own potential ascetical spiritual journey through purification, illumination and ultimately union. Once fired, enamels remain gloriously undiminished in spite of the vicissitudes of worldly time, as is clearly demonstrated by the above examples.

Jewel like colours sit in their cells demonstrating fidelity, purity and proclaiming their unique glory. It is by this very walled-up separation that their beauty exists. They do not ‘go outside’ their cells but instead remain inwardly faithful to the divine plan. They persevere in brilliance, ascetical beauty and steadfastness ‘to the end’ (Matthew 24: 9-13) and thus could be seen as a soteriological model of our own spiritual path towards salvation. In encasing a Holy Relic or Icon, cloisonné enamel becomes analogous to the protective ‘armour of God’ described in Ephesians 6,:13, ‘Therefore take up the whole armour of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand.’

Technique:

The cloisonné technique involves a number of stages. Firstly, the metal object upon which the cloisonné is to be placed must be prepared, usually by creating within it a recess within which the enamelwork will sit. The recess can be made using repoussé and chasing, stamping, or with the champlevé method in which a recess is either carved out of the metal surface or etched out in an appropriate acid bath. Often with the stamping or repoussé method the main depression was also pricked with minute indentations in order that the enamel should adhere better. This method is visible on the reverse of the icon medallion of Saint Paul (the front of which is shown above) in the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art in New York, as well as other medallions from the same set:

Reverse side of the Byzantine medallion icon of Saint Paul, demonstrating the ‘sunken’ (senkschmelz ) method of cloisonné enamel. Made in Constantinople, c. 1100, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gallery 303 Source: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/464546?=&imgno=2&tabname=label

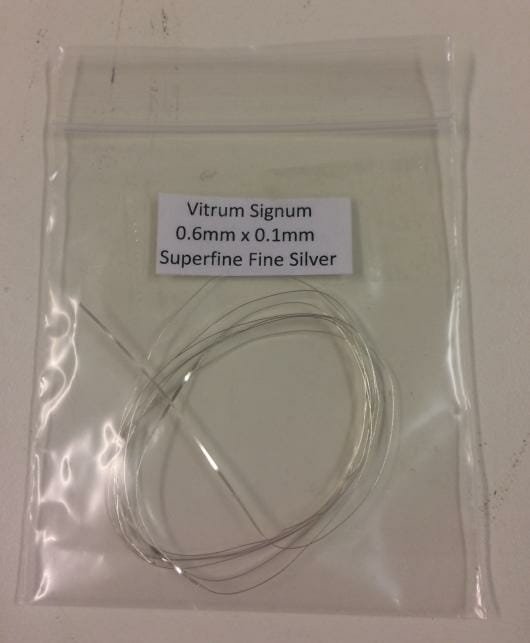

When the recesses have been prepared the cloisons can be added. These are made with very thin, flat cloisonné wires, which are formed into the required shapes and then attached to the base metal either by soldering them into the recess or by firing them without soldering into a layer of transparent enamel flux. The cloisonné wire is initially glued to the enamel surface with gum tragacanth to hold it in place temporarily. When the gum has dried, the piece is fired to fuse the cloisonné wire into the clear enamel and the gum burns away leaving no residue. The cloisonné wire work creates a pattern of partitioned chambers the tops of which are visible in the finished design. Cloisonné wire is usually made from fine silver or fine gold and can be made in any thickness, although it typically measures either 1 x 0.2mm or 0.6 x 0.1mm.

Vitreous enamels are opaque, transparent or opalescent and are a form of glass, being comprised of glass flux with silica, flint, soda or potash, and borax, each element affecting the fluidity, texture and composition of the enamel. Metallic oxides impart colour to each enamel and lead is added for brilliance, tin for opacity. The enamels in the various colours required for the design are ground in a porcelain or agate mortar and pestle, then washed several times in order to remove any impurities which would discolour the fired enamel. Using a quill or fine brush the enamel and water mixture is placed into each cloison chamber. In order to gently hold the enamels in place before firing, sometimes they are also mixed with a very weak solution of gum tragacanth.

The piece is allowed to dry completely before firing, which can be done by moving the prepared enamel briefly in and out of the kiln. The firing times and temperatures depend on the enamels and thickness of the piece being fired. The enamel sinks down after firing and so the process is usually repeated until the cloisons are filled to the upper part of the wire edge. The final stage of the process involves carefully smoothing and polishing the enamel and surrounding metal in order to achieve the desired final effect.

Steps in the making of the Saint Vincent of Zaragoza cloisonné enamel icon:

The plaque for Saint Vincent’s icon was made of fine silver. Fineness is a measure of a metal’s purity based on parts per thousand and ‘fine’ means that it is virtually free of impurities or alloying metals. Fine silver is ideal for enamelling as it has a bright shine which is luminous underneath transparent enamel and it also does not produce any fire-scale during the firing process.

The silver plaque was sent to me with its border already carved by Aidan and the lettering for Saint Vincent’s name engraved. I then filed and polished smooth the lettering recesses and silverwork, and created the main recess for his body and halo using a method of acid etching as follows:

Transferring the outline of Saint Vincent’s body onto the polished fine silver plaque.

Application with a brush of black ‘stop-out’ varnish to prevent acid erosion of the silver to be left unetched. This is later removed with acetone or white spirit.

The Saint Vincent plaque suspended face down in a bath of ferric nitrate acid. This process takes a number of hours to acquire the necessary depth, after which the plaque is neutralised in an alkaline bath and then thoroughly cleaned.

The silver plaque after etching the recess for Saint Vincent’s body. The stop-out varnish has been removed with acetone and the recess is then filed smooth and polished. Any remaining traces of stop-out varnish are carefully removed from the lettering with a diamond encrusted needle file (above). Then the plaque is soaked clean in ‘pickle’ and washed, after which it is ready to be enameled with an initial layer of transparent silver flux.

Grinding and washing silver flux enamel with a pestle and mortar to remove impurities. Any impurities would impair the appearance of the enamel causing spots, discolouration or cloudiness. The coloured enamels to be used subsequently are later prepared in the same way.

Application of a thin layer of transparent silver flux, which is then fired. The cloisonné wires are then shaped and then fired into this flux layer in order to affix them to the plaque.

The ‘superfine’ fine silver cloisonné wire, 0.6mm x 0.1mm, which was used in this project.

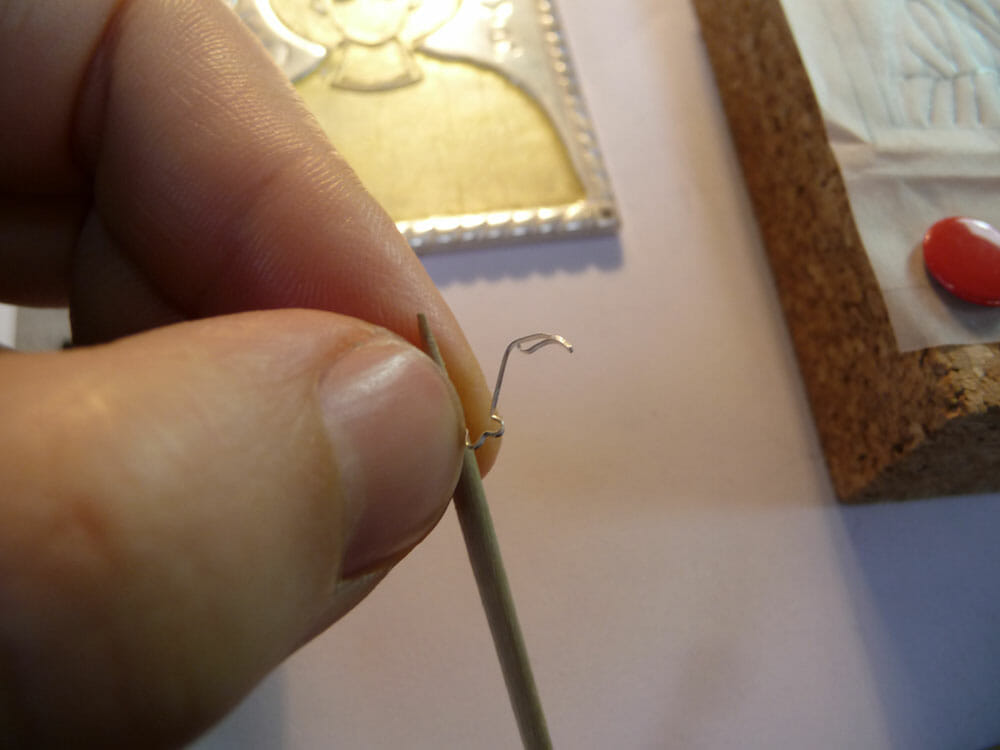

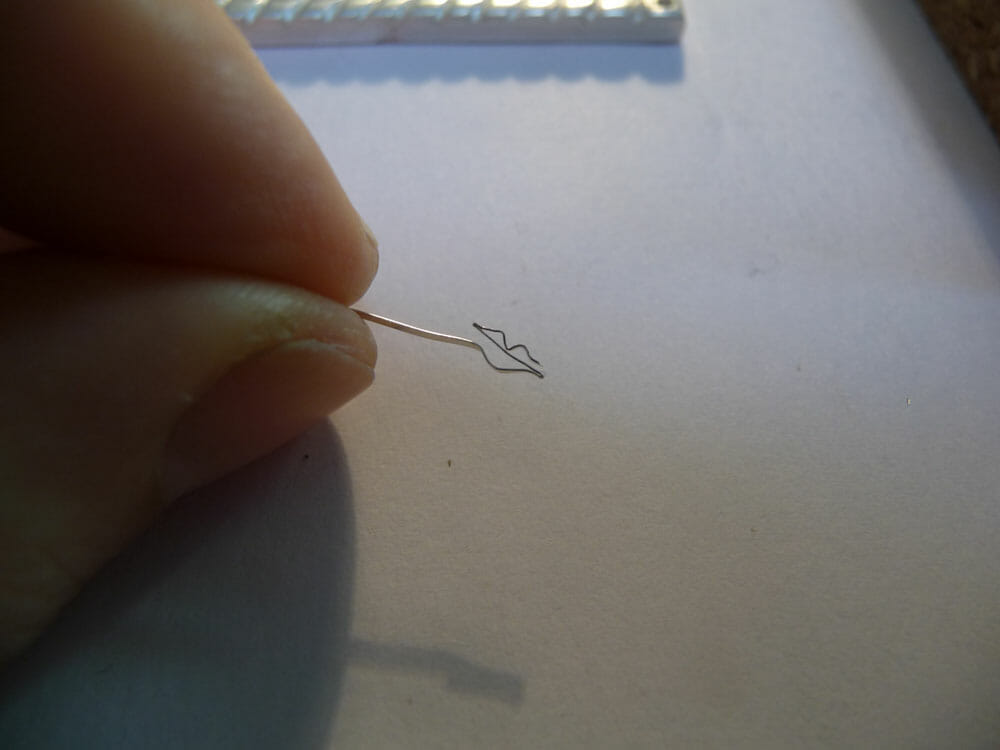

Christabel at work shaping the fine silver cloisonné wires using a variety of tools.

Some of the tools I use for shaping and cutting cloisonné wire: pliers of various types, a cocktail stick, pins, a dental pick, fine tweezers, a scriber and diamond needle files.

Shaping Saint Vincent’s nose and eyebrows with a cocktail stick.

Saint Vincent’s mouth.

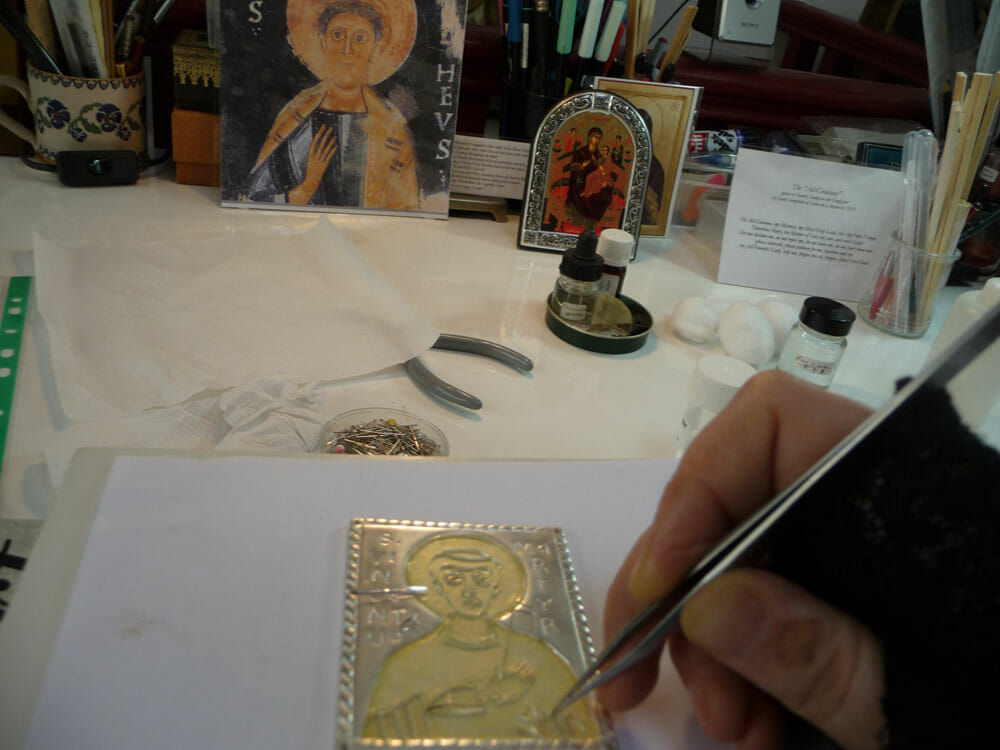

Arranging the shaped wires on the fluxed plaque as they are formed. The wires are very lightly glued in place on the flux surface using a dilute solution of gum tragacanth which burns away in the kiln leaving no residue after firing. Here Saint Vincent’s arms are being put into place with his icon looking on in the background.

The plaque is then fired at about 860°C and, in this case, a little more flux is then added to secure the wires. The plaque is fired again to set them firmly in place. At this stage I clean the panel and wires carefully with water and a glass brush, and then the coloured enamels can be prepared and applied.

Some pieces of ‘lump’ enamel used in the project. Lump enamel is enamel in its solid unground form, which is purer than pre-ground enamel.

My palette of enamels for the project. Once the enamels are ground and washed they are placed into small lidded pots to keep them clean and moist. Some pieces of lump enamel are displayed in the box lid as well as a quill, which is used to apply the enamel. Size 000 sable paint brushes are also useful during the application of enamel into tiny cloisons such as the eyebrows and lips.

The application of black enamel. This particular black has a high firing temperature so is added first and then fired in the kiln at about 850°C. Firing times are short for enamel, although this particular panel is 3mm in thickness so requires about 3 minutes. Thinner pieces often need only about a minute.

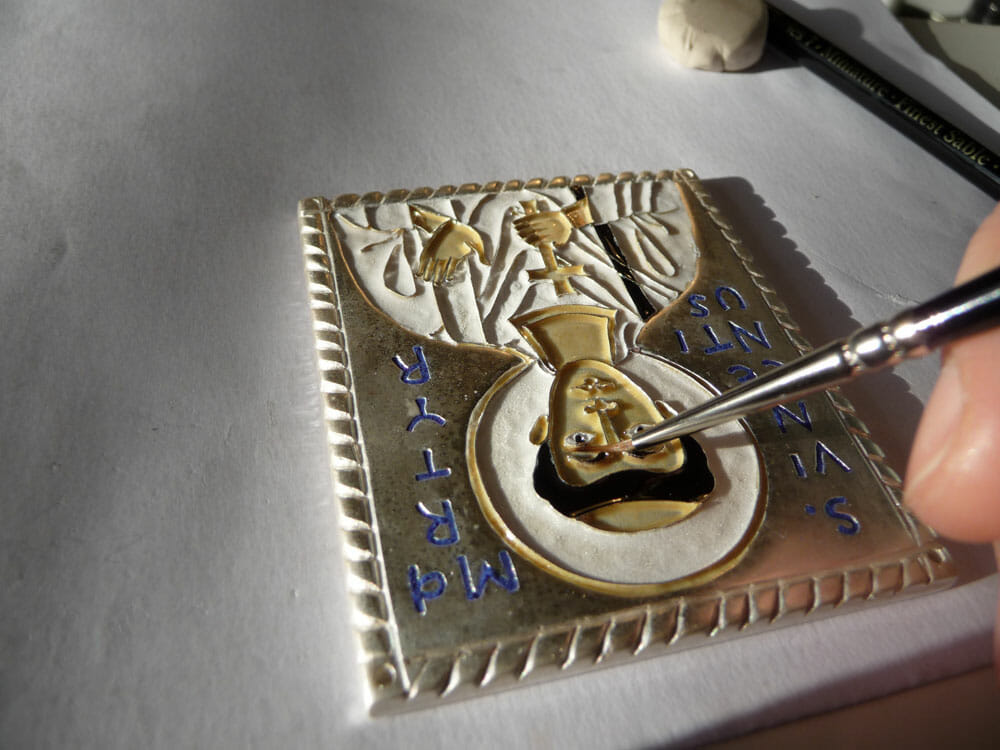

Further layers of black are added and then fired, after which cobalt blue lettering is applied with a sable miniature painting brush and opaque white enamel is applied to Saint Vincent’s robes and eyes.

The opaque white robes are applied using a goose quill. Then the plaque is fired again at about 820°C.

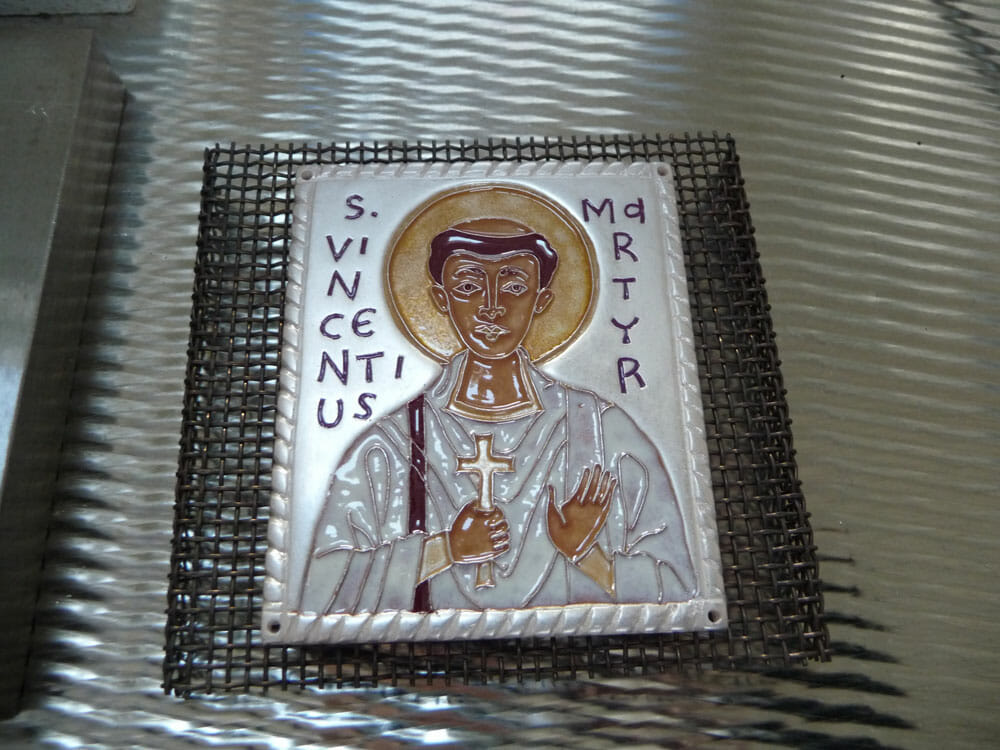

Immediately after firing, the enamel colours show temporary distortion and gradually develop their true colours throughout the cooling process. Here we see the icon plaque sitting on the wire rack on which it was fired. The metal area below is a flame proof surface which is necessary as the kiln operates at such high temperatures.

Application of the transparent royal blue halo and a third layer of the cobalt blue lettering.

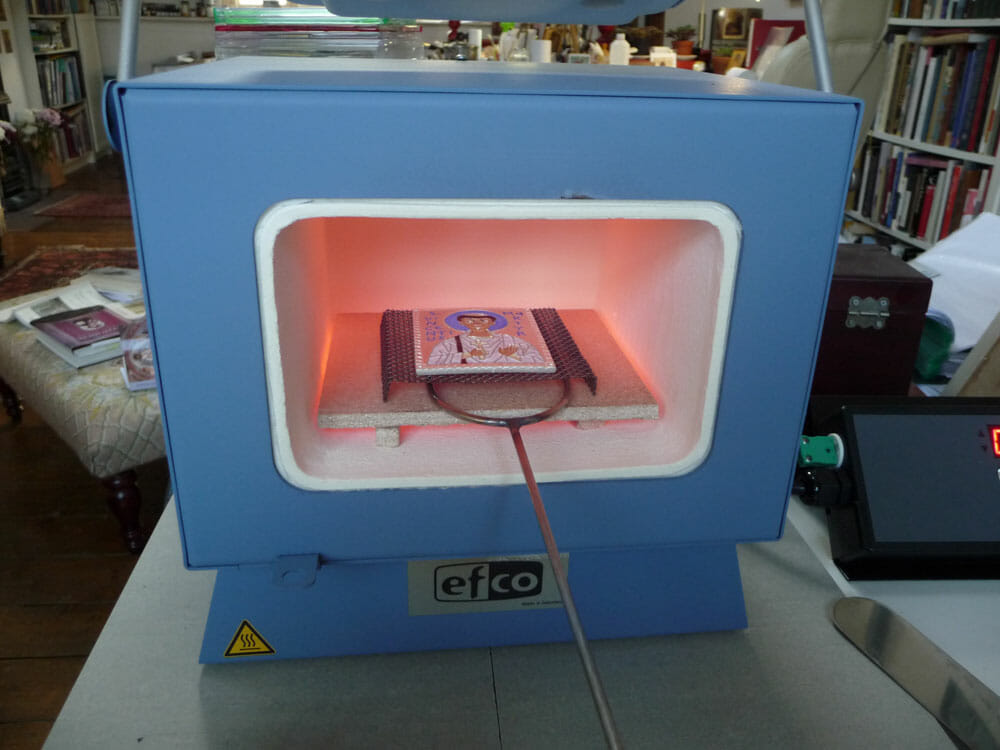

Another firing for Saint Vincent’s halo, lettering and flesh tones. Here, my electric kiln is shown momentarily open while the plaque is being placed inside with a firing fork. The little tile inside the kiln helps to keep it clean. To the right of the kiln, partly cut off in this photograph, is a digital temperature controller. Simpler controllers can also be used but a finer degree of control is useful, especially when very thin layers of enamel are applied such as in enamel miniature painting.

Then several layers of red and yellow enamels are applied and fired – red on Saint Vincent’s halo, lips and cross, yellow ochre on his cuffs and collar and a bright golden yellow for his orarion. These are applied last as have the lowest firing temperatures, usually between 740 and 800°C. If they are fired at too high a temperature their jewel-like colours will be lost and they may burn.

After the final firing the tops of the cloisonné wires are carefully ground and the plaque is polished to a brilliant shine. Polished fine silver shines more brightly than any other metal, returning over 90% of the light that hits its surface as brilliant white light evocative of humanity’s calling of spiritual Transfiguration and the shining of God’s glorious Uncreated Light into the world.

Saint Vincent of Zaragoza, Deacon and Protomartyr of Spain, the finished cloisonné enamel icon, by Christabel Anderson, January 2015.

What a beautiful jewel! It pleases me greatly to see this most fine and precious of all liturgical arts being practiced today. I have two technical questions:

How does the silver need to be maintained? Does it need frequent polishing? Would it be feasible to gold-plate the piece after enameling?

It is hard to tell in the final picture – did you grind the surface all the way down until the silver and enamel are perfectly flush, or did you leave enamel cells concave? What is your feeling on these two alternatives, both regarding aesthetics and cost?

Thank you Andrew for your kind comments and I trust that you are well. The silver will need occasionally light polishing as is subject to minor tarnishing depending on the environment in which it is kept, although fine silver tarnishes more slowly than lower grades of silver which are alloyed. A light polishing with a soft silver cloth would be sufficient. As it is solid fine silver, if the plaque was at some point scratched it could also be professionally repolished by a jeweller.

Fine silver is particularly good for enamelling as is so luminous underneath transparent enamel. Yes, it can also be gold plated after enamelling, although there is a minor risk of damage if there are any weaknesses in the enamel. In such a case the enamelling would need to be repaired and then the piece regilded. Many of the ancient pieces were copper or silver gilt (vermeil) and solid gold could be used if using the repoussé method (discussed above). Another option could involve using 24 carat gold cloisonné wire on silver and then gilding after enamelling.

In this case, the surface of the plaque is not uniformly flat as I felt that it added interest and character to the design. Cloisonné enamel can be concave, convex or polished to a completely flat surface. Personally I think that having some variation can in some cases add to the design, however most cloisonné enamel is ground entirely flat. I think it very much depends on the individual piece and what is most suitable for it. In terms of cost, the final polishing can take a little time but would not dramatically alter the cost of the piece. I hope that this helps answer you questions…