Similar Posts

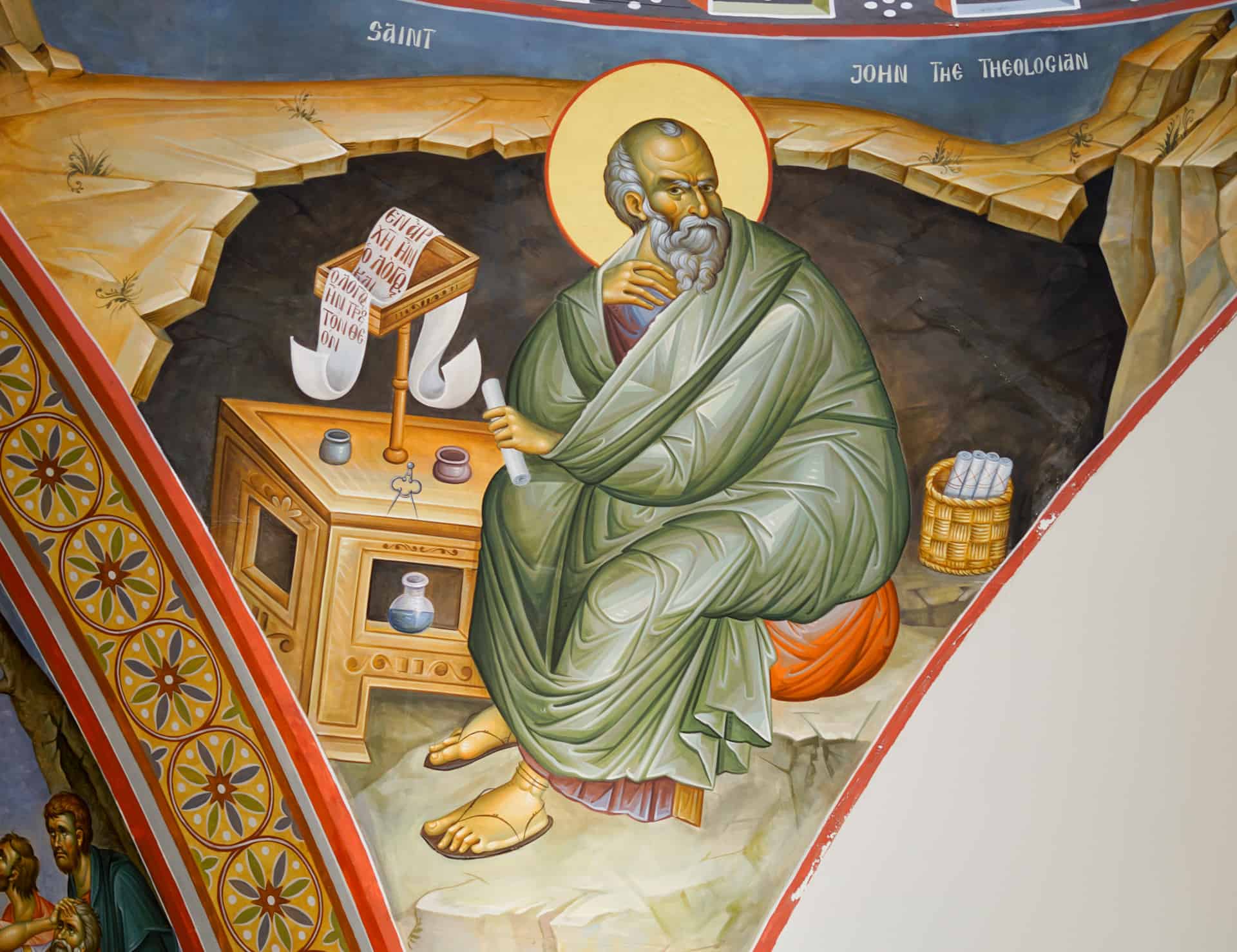

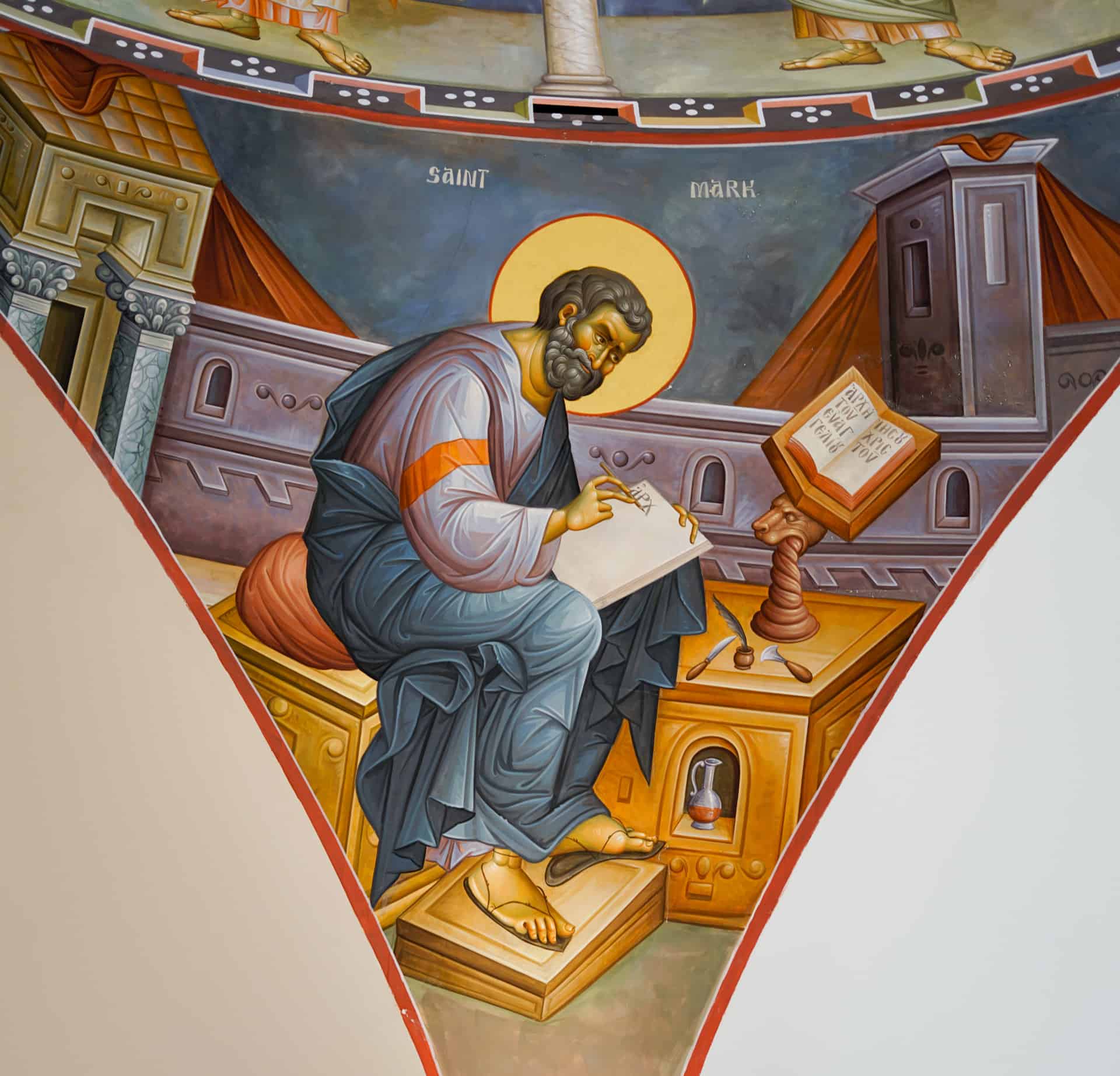

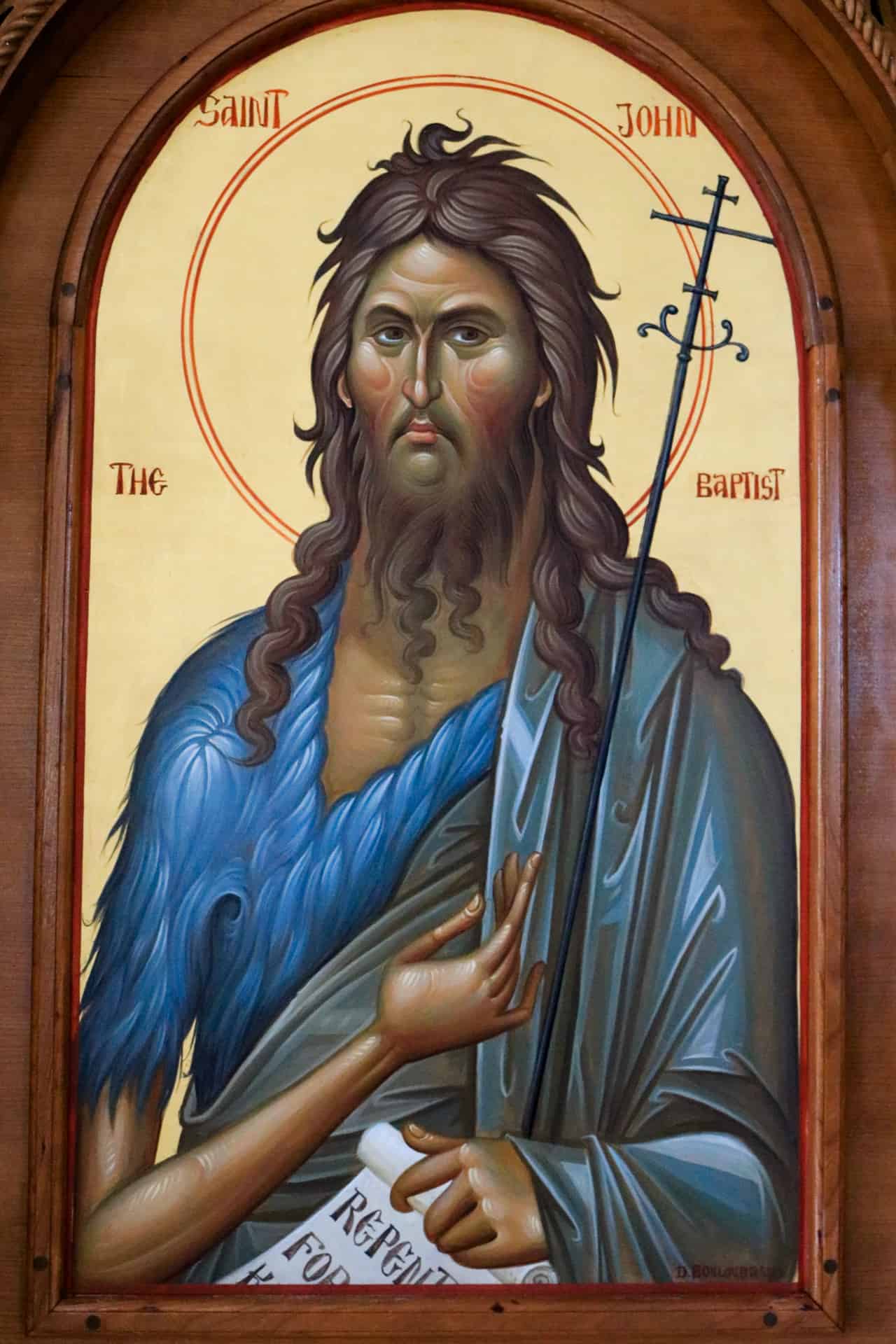

Dionysios Boloubassis developed a reputation as a talented iconographer in Greece before he immigrated to the United States in 2013. Over the past ten years he built up a new portfolio of work in America, which together with his churches in Greece, demonstrates his experience and skill in carrying on the iconographic tradition.

ORTHODOX ARTS JOURNAL: Let’s start by learning about where you are from.

DIONYSIOS BOULOUBASSIS: My parents are from Greece, but they immigrated to the US and I was born in Maryland. When I was still young, however, my mother and I returned to Athens. That’s where I was raised and received my education as an artist.

OAJ: How did you originally come to an interest in iconography?

BOULOUBASSIS: I loved art from a young age, but my love for art did not start in the Church. Rather I was fascinated by the Renaissance—by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, etc.

My grandmother was very pious. Going to church with my grandmother, I got in touch with the beautiful iconography of the Church. When I was 8 years old, for the first time I had the chance to see scaffolding in the church–the birth of the iconography, as it were, taking place. I understood that something exciting was going on! The scaffolding was related to the art on the wall! When I saw the iconographer up there, I said to myself, “That’s what I want to do when I grow up.”

When I was about eleven, my grandmother invited a family friend, a hieromonk from Mt. Athos, to come for a house blessing. His name was Fr. Joasaph. When he came, my grandmother proudly showed him some of my drawings. He was impressed and because he recognized some artistic talent, he offered to teach me iconography. So I began to paint with him. This hieromonk wasn’t doing Byzantine iconography, however, but rather a more Renaissance style, and he used oils. Nevertheless, from him I learned techniques such as mixing colors, how to hold and stabilize the brush, and so forth. I studied with him for about a year, back and forth. That was my start.

Around the age of 14, while visiting another church that was installing iconography, I saw scaffolding again. This time I began climbing up. The iconographer working there, Mr. Kopsidas, asked me, “What are you doing here?” I told him I was interested in learning to paint icons and I brought him my work to see. He recognized some potential and said, “You’re coming with me. I’m going to take you under my care and teach you. Wherever I am, you are welcome.” He gave me permission to follow him to his various jobs, and just as in the classic way of apprenticeship, I spent at least a year only watching him work.

When he finally said, “Okay, go and do it,” I was confident that I could. I quickly learned then how difficult it was! Initially I just did small things—painting borders, the clothes, etc. Along the way he was correcting me in a very fatherly way. I traveled with him to many towns and churches, working with him after school, on weekends, and during the summer.

OAJ: That seems like an unusual path—to begin learning on large-scale projects, rather than through painting small icons on boards.

BOULOUBASSIS: Yes, I essentially started from the wall. At home I was practicing all the time, of course, I would paint on a board, and do studies of Renaissance paintings.

My goal was to go to the fine arts school. At the age of 17, I did a year of special tutoring with professional teachers—regarding anatomy, design, etc. This was all in preparation for the entrance exams for the fine arts school. There were 1800 candidates and only 49 openings, and by God’s grace, I got in. This was the beginning of my official training. I finished with a degree that also allowed me to teach.

While I was a student, I continued working with Mr. Kopsidas, so I was continuing to grow as a Byzantine iconographer. It’s important to learn through hands on work with a good teacher. My education in the fine arts school opened my horizons and my mind to other art forms, but I received my Byzantine formation from apprenticeship with Mr. Kopsidas.

After graduation, I started working every day with Mr. Kopsidas. I stayed with him for ten years. Little by little he trusted me more and more and eventually I was able to do everything he needed. To this day we have a warm relationship and if I need anything, he is ready to advise me.

Eventually I decided I needed experience with some other iconographers, so I left Mr. Kopsidas and worked with other professional iconographers for three years. Then I started my own business—I was 32.

OAJ: How did you make the transition to painting in the United States?

BOULOUBASSIS: As a result of the Greek economic crisis, I had to start thinking about other opportunities. Because I was born in the United States, I had dual citizenship, which made it possible for me to live here. Plus, I still had family in Baltimore.

Initially I just came to investigate the potential to work here. I wasn’t sure that I could be successful as an iconographer in the United States. People encouraged me, saying that if I could secure the painting of one church, more opportunities would open up.

OAJ: How did you end up painting your first church in the US?

BOULOUBASSIS: It was all about the timing. My family and I were attending St. Mary’s Antiochian Church in Hunt Valley, Maryland. In those days, the parish was still meeting in a home. The priest had a vision and helped the people organize towards building a church. When I arrived the parish had been considering another iconographer. But the priest saw my work, trusted me, and brought me in. I was fortunate to get this opportunity.

OAJ: What projects have you done since painting St. Mary’s?

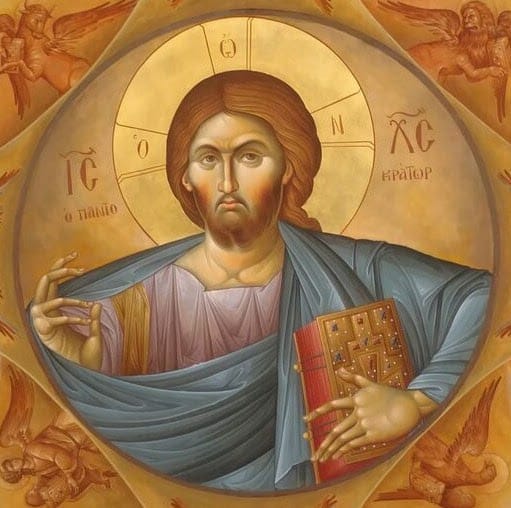

BOULOUBASSIS: I’ve also done work for Annunciation Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Baltimore, Maryland. I am working on icons for St. Nicholas in Flushing, New York now. I have made some work for Dormition of the Theotokos in Wyndham, New York. Now I’m beginning the icons for Prophet Elias in Salt Lake City–I’m working on the Pantocrator for the dome now.

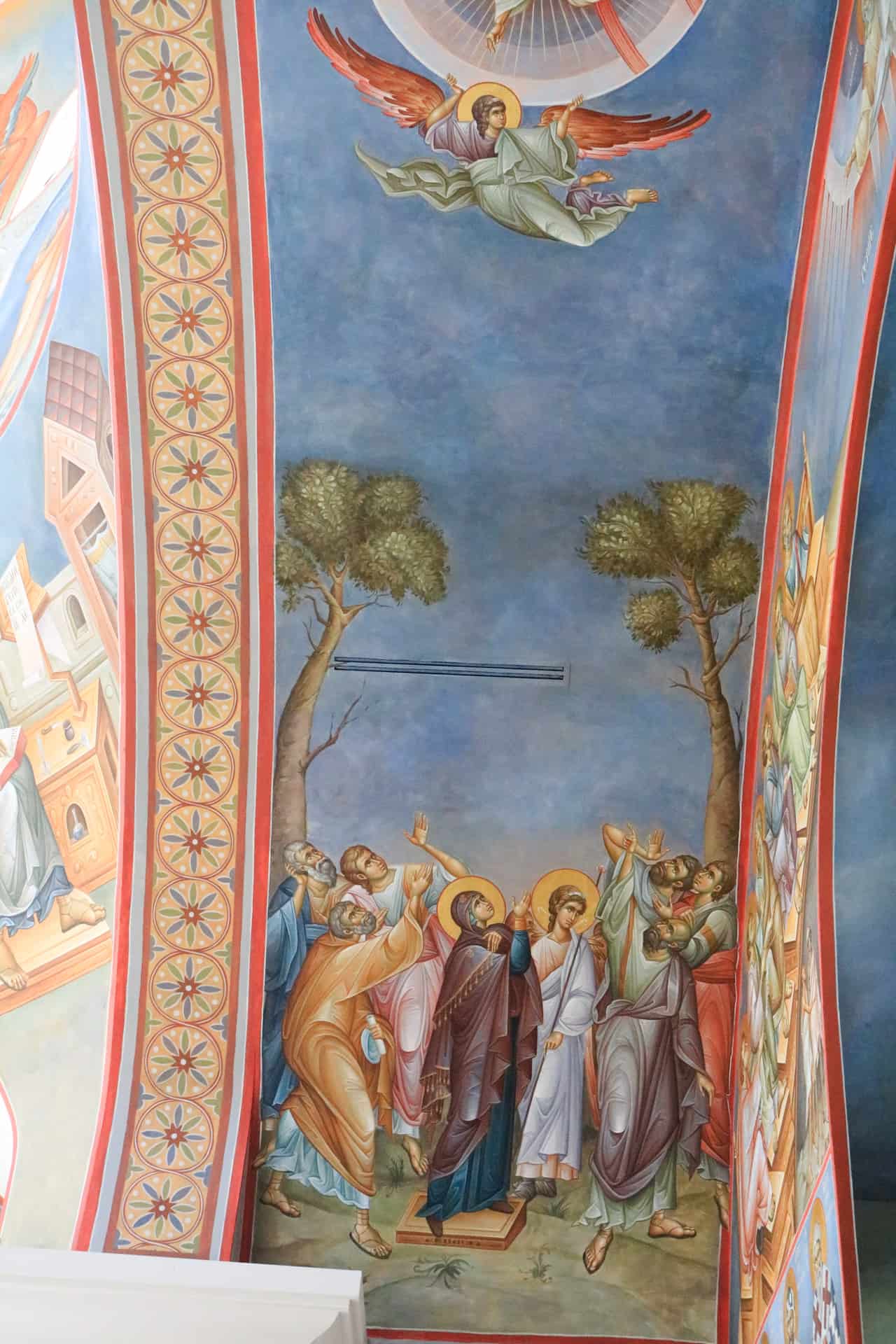

In Greece, I worked in many churches, as part of teams. I was part of a team that worked on a chapel in Aegina. I also painted in Aigio in the Peloponnese. I also painted the chapel of a charity called The Flame, which is dedicated to kids with cancer, based in Athens.

OAJ: Do you receive most of your clients via word-of-mouth?

BOULOUBASSIS: Yes, the clergy who are looking for an iconographer will talk to others who have recently hired one. There was also an article in the Baltimore Sun. It is a little difficult because I don’t have a team. I am doing all of the work myself and there is no one arranging jobs.

An additional challenge in the United States is that people were not familiar with good Byzantine art. They rarely think much about the iconography when building. But when they see really good iconography, they feel the difference, and everyone becomes enthusiastic. Even if they don’t understand why, they can feel that this is something elevated. This is my reward—to be able to help people connect more deeply to their faith.

OAJ: Can you describe a project that stands out as particularly challenging for you?

BOULOUBASSIS: Every work is its own challenge, but painting St. Mary’s stands out, partly for emotional reasons. I put a lot of effort in because I needed to communicate what I was capable of to those who are not familiar with my portfolio, but also to people who are not familiar with good Byzantine iconography. Because it was my first project in the United States, I felt the weight of responsibility to offer the most accurate and most beautiful representation of this art form.

OAJ: In addition to your teacher, Mr. Kopsadis, what other iconographers are you influenced by?

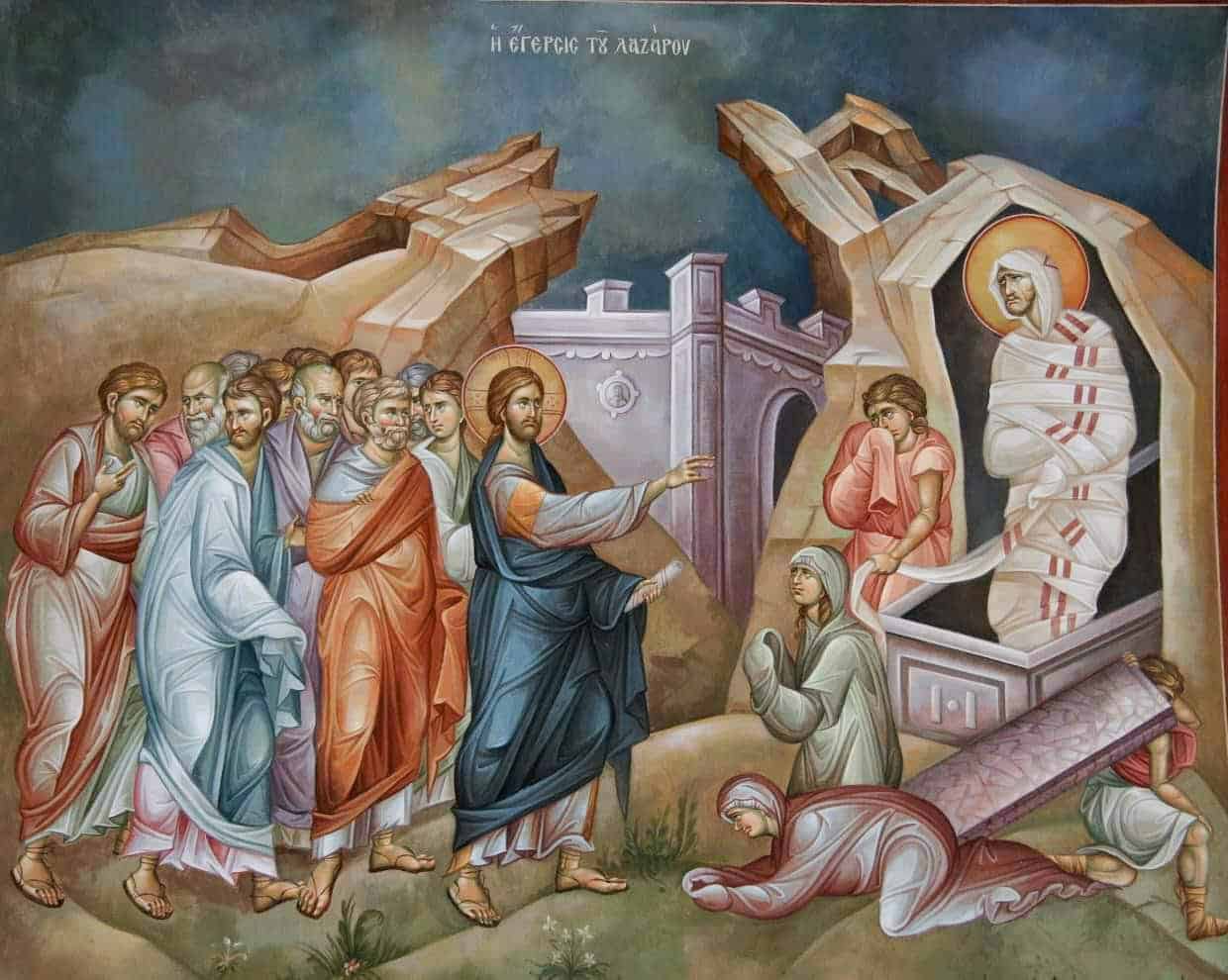

BOULOUBASSIS: There are so many—it’s difficult to name only a few. I would say Manuel Panselinos or Michael Astrapas. In the Cretan School—Theophanes. There are many others! I watch everyone and am inspired by everyone, taking bits and pieces.

OAJ: Tell us about the distinctive blue background to your icons at St. Mary’s.

BOULOUBASSIS: The blue background is traditional in frescoes. When the method developed, you were limited to certain colors because some colors would react to the lime.

When I paint individual icons on a board, I use traditional egg tempera. For churches, however, I paint on canvas and use acrylic, but I use blue backgrounds as if the icons were frescoed. I do something unique though—I play with the blue, making it more dark in some places, or more light. This results in a more sensitive effect. Some churches request an all gold background. I don’t recommend it—first, because it is not traditional. Second, because it takes your attention from the figures.

OAJ: Please tell us more about the Platytera from St. Mary’s, where the Mother of God is surrounded by a large body of angels, painted in grey.

BOULOUBASSIS: I made this choice to make the image more powerful. I discussed it with the priest, who was particularly interested in putting more angels in the image. But I did not want to distract from the image of the Theotokos. Instead I painted them in a monochromatic way, so that she would visibly be “more honorable than the Cherubim, and beyond compare more glorious than the Seraphim.”

OAJ: What does your process for planning a church look like?

BOULOUBASSIS: First, I go to the church and take exact measurements. Then I paint on canvas in my studio. Then I take everything and I spend a month or two months installing all of the canvasses. When it is all done, you cannot see the difference between my canvas paintings versus fresco.

OAJ: When you are painting newly canonized saints, what challenges do you face?

BOULOUBASSIS: The new saints—we don’t actually have prototypes for them, so we have to create a prototype. The danger is that because we have so many photos of them, iconographers are tempted to paint the face like a portrait, which is not the Byzantine tradition. We can paint a portrait of them separately, of course, but this is not an icon. If you want to do an icon, you must focus more on the internal characteristics rather than on the external. I have painted many of the new saints and I try to avoid painting them with too much of a natural likeness.

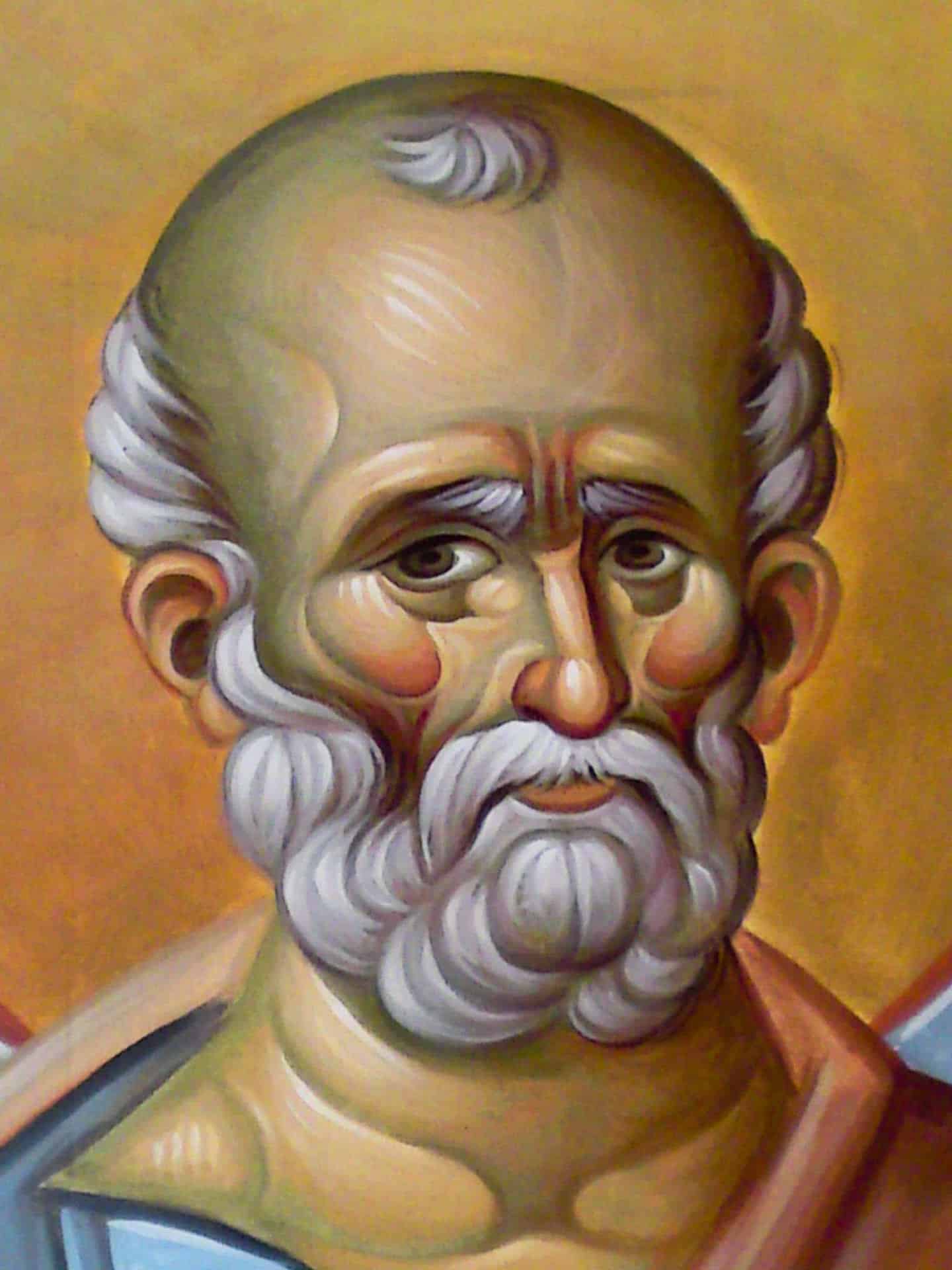

OAJ: The faces of your saints tend to be round and painted with rosy color, as opposed to elongated and olive toned. What is the significance of this choice?

BOULOUBASSIS: There are two main schools of iconography – the Macedonian School and the Cretan. The main representatives of the Macedonian style, which developed in the 1300s, were Panselinos, and also Astrapas. This style was more colorful. The other school is the Cretan style, which was founded by a monk. The aesthetic is more restrained, ascetic. The reason for this is to intentionally focus attention on the interior spiritual struggle, rather than the goodness of external life.

Before the development of the Macedonian School, there was also the Paleologic style. In Turkey you can see these churches, painted in the 10th and 11th centuries. You can see this style in Chora Monastery, for example, in Istanbul.

OAJ: How do you decide which style you will use as an inspiration when you’re planning a church?

BOULOUBASSIS: When the church is small, I like the style to be more ascetic, interior. But when it is large, it doesn’t work to do that. It doesn’t fit. It’s important that when people come to the church they see something beautiful and uplifting, not something too austere or strict.

In modern iconography we have rules, but within the tradition there is freedom. There are certain “dogmas” in iconography—you can’t change certain colors and forms. When we paint St. Peter, he is always painted with yellow. When we do Christ, always with blue. When St. Paul, we paint him without too much hair. We cannot change it—these prototypes are from the beginning. It is very dangerous when one iconographer wants to express themselves, because it is so easy to step outside of the dogma. That’s why we must be very careful. You cannot change too many things. It’s not a personal expression. You express the dogma of the faith, so you must be very careful.

But over time, when many people make the same change, the art form develops appropriately.

OAJ: Having painted and worshipped in the United States for eight years, what are your hopes—artistically or spiritually—for the Orthodox in America?

BOULOUBASSIS: As far as iconography goes, I don’t have anything specific to say because it should be universal for the Orthodox in general. As far as the Orthodox Faith, because I see the influences from all of the different places—Serbia, Romania, Russia, etc. I hope that somehow that we will find a way to join forces and stop being fragmented and build a solid Orthodox representation in America.

In my homeland, we take our faith as a given. I’m impressed in the United States that so many people are searching. Through their personal search, and through studying history, they are finding their way to the Orthodox Church. Without anyone persuading them, on their own path, they find Orthodoxy. This is very amazing to me. I would be very grateful if my art–the way it expresses Orthodox spirituality–can help people outside the faith make their journey, or help those people in the faith to re-connect to the faith and the teachings of the Church.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

When I first saw photos of St. Mary in Hunt Valley after he had completed the dome, I was amazed by his powerful combination of historic precedent – for example the influence from Panselinos’s frescoes at Protaton on Athos – and a dynamic creativity within the received tradition. I knew that if I ever had a chance, I’d try to hire him for any monumental project. By the grace of God and with the help of our beautification committee, and at the approval of the entire parish, Dionysi will arrive in Salt Lake City next week to begin work on our dome, and then later in the summer for our Apse.

As a church designer, I’m acutely aware of a shortage we have in this country – that of iconographers who are really competent to paint the walls of a large church. What a wonderful resource Dionysios is, living here in the USA. He paints solidly in the Byzantine tradition (as opposed to Slavic), so his work is perfect for the many large Greek and Antiochian churches that are being built nowadays. And with such rich pretty colors, his work is beautiful in a way that is particularly accessible to the eyes of Americans and converts. I’m sure he has a long and prolific career ahead of him!

Could you articulate here some of the major differences between Byzantine tradition and Slavic that you eluded to in your comment? I thought that the Slavic tradition was based on the Byzantine tradition.

Certainly. On the whole, iconography in Slavic and Greek lands is very similar, and is best understood as regional variation within the same religious art tradition. Nevertheless, when considering large numbers of historical examples over many centuries, we can certainly observe some different tendencies that prevail in the different nations. Iconography in Greek churches tends to be more graphic in style, with sharper edges, higher contrast, and more saturated and opaque coloring. Slavic iconography tends to be softer, paler in color, more transparent. Many people perceive Greek iconography as more intense and assertive, and Russian iconography as more gentle and introspective. These are generalizations of course, and there many exceptions, but it is consistent enough that most people can see the difference, and it is common for churches to want iconography in the style that fits their ethnic self-image. The Greek Orthodox commonly call the iconography they prefer the “Byzantine Tradition”. The reality of that title is sometimes debatable because modern Greek iconography does not always conform so well to the style we see in actual Byzantine art (pre-1453). In practice, the word Byzantine is often used to mean “not too Russian looking”.

ABSOLUTLY awe inspiring . Proof that the tradition lives and that the new paradigm is adherence to the tradition of iconography.