Similar Posts

We often hear it said that traditional Orthodox liturgical arts are reviving. But how far advanced is this revival, how mature is it, and what in fact are we reviving? In this article I would like to stimulate discussion by briefly considering three related subjects: indigenous iconography, maturity, and features of a healthy climate that would help produce better liturgical artists.

Indigenous iconography

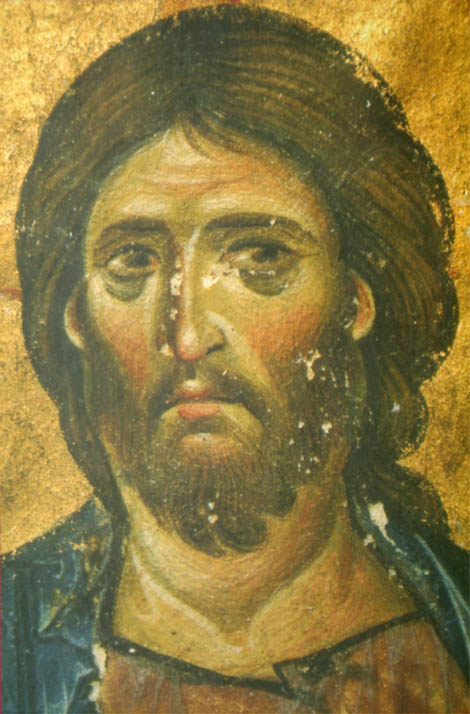

The icon tradition expresses timeless, divine truths through human endeavour. No man-made work can exhaustively express the wealth of God’s wisdom, which is why there are diverse iconographic styles.

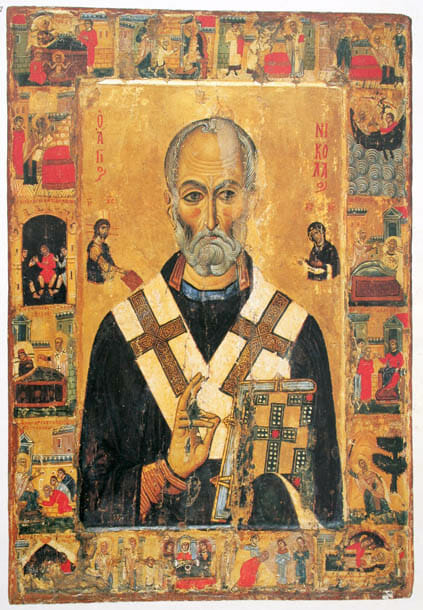

Each culture and individual brings something of their own to the icons they paint. In this sense, icons are a mini incarnation, a union of divine and human energies. They are Pentecostal, declaring the same divine truth in different languages. Well made icons are always recognizably icons, so clearly there are characteristics common to all good icons. But the fact that we can date and give the provenance of works by their style alone shows the great diversity there exists within these parameters.

In our times the conservative nature of Orthodoxy in general and its arts in particular is emphasized. But we need to be careful of overemphasizing this unchangingness. It is often the case that when a tradition is revived it is more conservative than the epoch that it seeks to emulate. Renewals can prove to be pseudo-revivals, at least in their formative stages. This tentativeness is due to the lack of confidence in handling the new language, and fear of debasing the tradition through innovation.

Iconography in our times is in such a “neo-Byzantine” phase. Liturgical arts in Russia became debased from around the time of Peter the Great (1672-1725) and in Greece and the Balkans from around the late fifteenth century, after the Turkish conquests. Traditional iconography began to revive in Greece in the mid twentieth century, largely through the work and writings of Photios Kontoglou.

In Russia, a revival arose from the late nineteenth century through the Russophile movement and the cleaning of old icons at the beginning of the twentieth century.

So the revival of traditional Orthodox liturgical arts has begun, but we must consider it as in yet an immature stage. It is still our second and not our first language.

A discerning culture

How does one distinguish between authentic variation and arbitrary innovation in icons? What is the difference between bad workmanship, egotistical novelty, and inspired contributions to the icon tradition?

I think the best response is not so much to answer this question directly, but rather to ask what is the healthiest environment for iconographic endeavour so that it is difficult for liturgical artists to get it wrong rather than difficult to get it right. The great painters of the past have not appeared out of a vacuum, but are the culmination of a community, of a cultural environment. They are healthy plants because of healthy soil. St. Andrei Rublev would not have been possible without St. Sergius of Radonezh and his monastery and the genius of Prokhor of Gorodets.

So what might be the characteristics of such a healthy icon culture?

In no particular order of priority, I suggest that the following are some key features of an intellectual culture likely to create good liturgical art, and by liturgical art I mean the whole range, from psalmody to architecture, church furnishings to iconography.

1. Centres of serious learning.

Although we can learn a lot by ourselves – by trial and error, by reading, by observation – this can be a slow way to learn. And without more experienced eyes critiquing our work we can get a false impression of our worth. By far the best way to progress forward quickly is to learn from those more experienced. When we have done our apprenticeship we can then explore stylistic variation with confidence.

Schooling may take the form of apprenticeships with an individual master or in a larger workshop, or full-time and part-time courses. Russia has at least one such five year full-time course in Petersburg, the St Tikhon Institute. In Greece and Russia it is common for monastics to learn under a fellow monastic icon painter. This is an easy method since as monastics the master and pupil are living in the same place anyway. And also the monastic teacher does not usually have the financial pressures that deter many professional iconographers from taking on an apprentice. The more successful lay iconographers will however sometimes need to take on assistants to help them keep up with orders.

2. A discerning awareness of cultural trends.

The fact that the style of iconography in the great epochs was always varying and responding to changes in the mother culture shows that the icon community was intelligent and alive to current cultural movements.The great iconographers did not of course embrace every trend of their surrounding culture, but they were clearly aware of the main currents. While the contemporary icon painter does need to identify which elements of their culture are sterile or even destructive, they also need the humility to identify good or useful elements and be open to integrate them into their work.

The great icon painter of the twentieth century, Fr. Gregory Krueg, could only have painted what he did because of his background in the art movements of Paris before and during his time.

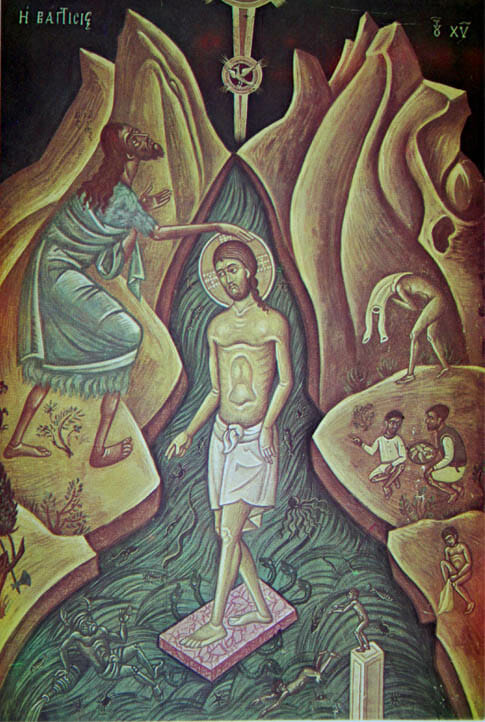

The founder of the “Neo-Coptic” school, Dr. Isaac Fanous Yossef, amalgamated elements of Cubism with old Coptic iconography.

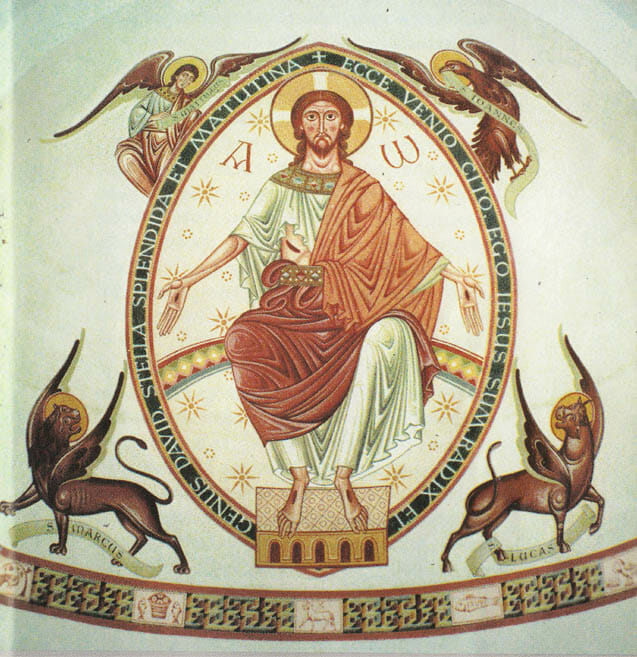

Archimandrite Zenon (Theodor) of Russia is drawing on the Romanesque and early Roman traditions of western iconography

Moving back in time, the different phases of Byzantine liturgical art were generally caused by swings in the intellectual world between emphasis on asceticism and hesychasm on the one hand,

and the Greek classical tradition on the other (introduced through such things as classical illuminated manuscripts and a revival of philosophical learning).

All Byzantine iconography aimed to reflect a transfigured world, but some schools drew more on the urbanity of the classical style while others eschewed this in favour of greater simplicity and flatness.

The diversity in traditional Russian works result from the diversity of the regions that produced the different schools – Kievan, Novgorodian, Muscovite or whatever. Elements influencing their styles include the degree of contact with western Europe or the east, and whether the areas of icon production were predominantly urban – in which case more intellectual works are produced – or rural, which inclined to a more folk tradition. The mercantile and independent republic of Novgorod produced work both urbane and dynamic. Moscow, with its hesychast tradition introduced by St. Sergius or Radonezh and his followers, developed a subtle, delicate, intellectual style, most notably in the persons of Prokhor of Gorodets, Daniil Cherni, Theophan the Greek, Andrei Rublev and Dionysius. Northern more rural schools tended to a more earthy, folk style.

3. A culture of intelligent questioning united to respect for the wisdom of tradition.

We stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before, and it would be folly to reject their experience. On the other hand, what commentators say about tradition is not always correct, or at least, they sometimes tell only one side of the story. So, while acquainting ourselves with what is written by scholars and thinkers, we need also to go straight to the masterpieces of the past and study them directly. The student needs to learn how to analyse masterpieces to discover their technical secrets and get inside the thinking of their creators. Why did they do what they did? What were their influences? Why did they choose that colour or form and not another?

4. Courage.

It is relatively easy and safe to limit ourselves forever to copying masterpieces. While intelligent copying is necessary in the early learning stages, it suggests a spirit of fear if this continues to the end of one’s life. Freedom is a risk, but it is dangerous to suffocate it in the name of fear.

It is certainly better to make sensitive copies of icons than profane or distorted works in the name of originality. However, we do not want to be like the man who buried his talent: “Master, I know that you are a hard man, harvesting where you have not sown and gathering where you have not scattered seed. So I was afraid and went out and hid your gold in the ground. See, here is what belongs to you.’ (Matthew 25:24,25)

God has not made us like machines endlessly to churn out copies. He will not punish us for being ourselves, even if we stumble a bit while finding our own unique way. We can use study icons to experiment with different styles, so we needn’t expose people to our experimental mistakes. Once in our studies we have found elements that work then we can incorporate these into our public iconography.

5. A deep spiritual life.

The ultimate litmus test of whether an aesthetic choice accords with truth or not is personal knowledge of God, direct experience of His grace. If we have heavenly music in our hearts, we can easily tell whether something in our work harmonizes or jars with grace. This spiritual life is nurtured by prayer – both liturgical and inner prayer, non-judgement of others, acceptance of God’s will, fasting, patience, study of the Scriptures. It was said of St. Andrei Rublev that he was a very meek man, and it is evident in his works that this meekness guided his aesthetic choices.

6. A commitment to sacramental and liturgical life of the Church.

Icons do not exist as isolated objects on a wall but are part of a larger liturgical culture of praise. It is only by living this liturgical life that iconographers can make wise choices in the development of their style.

Also, personal spiritual life in Christ is only possible within the communal life. We are made in the Holy Trinity’s image as members of a community and not as isolated individuals. Icons exist to be a means of communion between those in heaven and those on earth, and iconographers need to know this communion of the saints from liturgical and personal experience if their icons are to have the gravitas of authenticity.

7. The test of the faithful.

In the end, the test of our iconography is whether or not it proves to be a blessing to the praying faithful. Of course, even a badly painted icon will be a blessing inasmuch as it bears the name of the saint or feast and people pray in front of it. But with regards to how much the way an icon is painted reflects a transfigured world, this will become evident by people’s response to it.

8. Artistic gift.

While piety is needed to make good icons, so also is native ability. If the icon tradition becomes known as merely a copyist’s craft, operating under arbitrary rules, it is unlikely to attract the native talent it needs. Whilst the gifted artist’s creative impulse for originality needs to be purified of egotism, so also tradition needs to be awakened and renewed by creative talent. As the surrounding culture changes, so does the language used to address that culture need to adapt. And this needs inspired talent as well as knowledge of the past.

Thank you for this post. I think there is a bubbling deep under the surface to create, revive, actualize a truly western iconography that is steeped in tradition without being bland copying. I have found this bubbling in myself, but have also seen it in those artists I have encountered. I have seen it in your own work, in some of the church designs of New World Byzantine and in many others.

Yet I can only truly talk for myself. Faced with so much disorder, so much excess in our culture both lay culture but also in so called “christian culture”, my feet move very slowly towards my desire for this new art to appear. There is so much chaos in liturgical art, so much fluff or even subversive elements, that I spend hours pouring over medieval art, trying to grasp what went wrong and how to backtrack without sentimental pastiche.

Certainly you have given the right elements we need to arrive at our goal. I think this space and any space where liturgical artists can exchange and visit each others works will also play a role in bringing this about.

I agree entirely with your cautiousness, Jonathan. Total absorption in masterpieces, trying to discover their timeless principles that informed them, is the surest way forward.

Although Aidan is speaking about iconography, all of it can be applied to music.

I got SO excited reading it, because it articulates so beautifully the things that have been churning in my heart and soul for a long time. One of my almost daily struggles is trying to understand how we will go forward in this country to develop “indigenous and mature liturgical arts,” as the article is titled. Many have charged forth in the past 30 years to attempt this, often in zealous ignorance. My concern is how we will do this with zealous wisdom.

This article states very clearly, and I believe accurately, what will be required for the Church in America to be able to do this. And it also makes it clear WHY it is taking such a LONG time. Brand new converts to the Faith (even very gifted ones) are not in a position to discern what is the appropriate indigenous artistic expression of a 2,000-year-old Faith. Neither are those who do not maintain “a deep spiritual life nurtured by liturgical and inner prayer, non-judgment of others, acceptance of God’s will, fasting, patience, and study of Scriptures,” as the article states.

And there is the rub, because most of us are failing pretty miserably at this, partly because it is getting harder and harder to do outside of a monastic or quasi-monastic environment. We live in a country where we have been told we can “have it all.” And we tend to believe it. This has led us to some very “fuzzy” thinking regarding our salvation, our communion with God, and what a transfigured world looks like. I believe many of us think we can actually have these things WITHOUT giving up anything, without any sacrifice, struggle or effort. If this assumption weren’t so tragic, it would almost be comical.

I strongly believe that until Orthodox believers gifted in the arts fully commit to becoming all that we are called to be by Christ and His Church, we will not begin to see appropriate indigenous and mature liturgical arts in America. What I love about Aidan Hart’s article is the assertion that ALL of the elements must be present, not just talent and not just piety.

I am looking forward to reading more and becoming involved with this website.

God bless you all for your efforts on this website! May it be to the glory of God and the building up of His Church.

Thank you, Valerie. I think that missionaries need first to be prophets, in that before speaking the word of God in a culture they need to discern/hear what God has already revealed to it – just as St Paul did on the Areopagus. Their words will then affirm what is good as well as direct people further. This is what I feel we need in our liturgical arts.

I have just completed a fresco in our present church in which I have tried to unite aspects of early western (chiefly Romanesque) and Byzantine liturgical art. I will post up images when the scaffolding has gone and I have photos – later this week.