Similar Posts

Aleksandras Aleksejevas is a Lithuanian Sculptor who now works our of the UK. He has been member of the Royal British Society of Sculptors since 2004 and also a member of the International Art Foundation of Moscow since 2000. He works in several mediums, though his favorite is bronze, and it is in this medium that he has chosen to give a fresh voice to the ancient art of the bronze icon. I had a chance to interview him to discover more regarding his thoughts and approach in this traditional medium for iconography.

Pageau– Your bronze icons set themselves in a long line of historical precedents, from the iconography on bronze doors, on bells to the later tradition of Russian cast travel icons and crosses. Can you tell us a bit about how you interact with those precedents in your work?

Aleksejevas– Bronze iconography is an ancient art; its history counts more than 16 centuries.

Usually, people know its monumental forms, for example, the Novgorod bronze gates or the Gates by Ghiberti in Italy, the Suzdal gates (though a different technique was used to make them). It is also associated with reliefs on bronze bells but, nevertheless, first of all we know it through the Old Believer traveling icon.

This type of icon is a phenomenon deserving a special discussion. It is almost unknown in the West. I, as an iconographer, of course, am and will stay under the influence of all these images which I saw in reality, in the form of illustrations or somehow else, for example, in the story “Bell” in A. Tarkovsky’s film „ Andrey Rublev”.

For my first icons I chose prototypes from the icons carved on wood, but gradually the horizon of researches extended and deepened. Thus the interest, to learn as much as possible about the tradition of bronze iconography – from where it came, how it developed and what it represents today, appeared.

The results of these researches and finds gradually started changing the icons I produced. There appeared tops and ornaments on them; I also started to use methods and devices which characterize the Old Believer icons.

Alex Aleksejeva. Our Lady of Kazan with a top Savior Mandylion with two cherubim. Notice the relation with Old Believer icons below.

Pageau– I was recently introduced to the wealth of imagery in Lituanian folk carving by the American iconographer Marek Czarnecki who is of Polish origin. Like much religious folk art there is a directness and frankness in the abstraction that has an undeniable force. It is difficult for me not to see some of that in your cast icons. Can you tell us a bit about Lithuanian folk art and how/if it is a part of your re-interpretation of the ancient models?

Aleksejevas– Lithuanian sculpture, especially wooden, is a unique phenomenon. Not every small country has its own sculpture, especially an ancient and so refined one. When I lived in Lithuania, in Kaunas, near my house six museums exposing the Lithuanian sculpture were situated, and two sculptors working with wood lived in the neighborhood. The sculpture surrounded me everywhere; I have been contemplating it since my childhood.

Today, looking at my works, sculptures and icons, retrospectively, of course, I see the influence of the Lithuanian sculpture on all my creativity.

In what is this influence seen? It is expressed in the commitment to “antiquity”, in the line clearness and simplified look transferring visual information in the concentrated form, without being dissolved in details, in its vertical position and hierarchy where small parts are always subordinated to big ones, in special rhythms of construction in space.

When speaking about iconography, this influence is more distinctly visible in my early icons, later they began to be filled with other archetypes, more characteristic of a bronze icon.

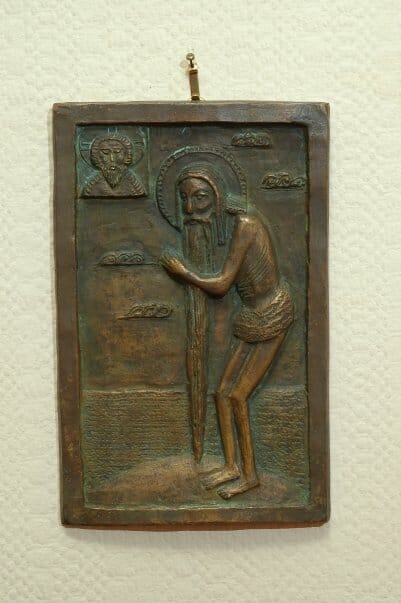

Aleksejevas. Early icon of St-Peter the Athonite. Notice folk tendencies in the type of abstraction in the face of Christ and the body of the saint.

Pageau– There is also a discussion with modernity in your icons through the almost geometric simplification and the matter of fact presentation in both the drawing and facture. How do you see the relationship between the traditional imagery and a more modern design in the context of a liturgical art?

Aleksejevas– During my studies at art school when I became professionally interested in sculpture, I started penetrating into its essence; I liked very much modern sculptures by Robertas Antinis the father, made in modernist or postmodern style but based on the Lithuanian antiquity, and the works by Lionginas Shepka, a great carver on wood, such a rural Michelangelo.

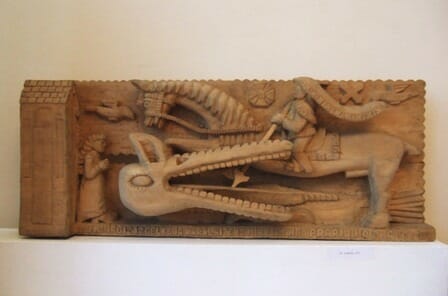

Woodcarving by Lionginas Sepka or St George and the Dragon

Later these addictions were reflected in my works – in sculptures and icons. I had an aim not to produce innovations peculiar to modernism but rather to stick to antiquity. Modernists of the beginning of the XX century: Modigliani, Picasso and many others also found inspiration in archaic forms. It is worth remembering a well-known “African” exhibition in Paris at the beginning of the XX century which laid the modernist foundation in art and proposed new ways of image performing based on ancient archetypes. These forms are simplified to a scheme and it gives them force. Many modern artists are “products” of modernism, however, some of them see their creativity in following innovations but others in returning to roots. I see myself among the last ones.

Liturgical art is based on a canon. Icons were made throughout the centuries. In church one can see icons dating from the 13th, 17th and 21st centuries. However, the sense of an icon always remains invariable; the Crucifixion will always be the Crucifixion. If an artist sticks to the canon, he won’t make mistakes in work. Relying on the experience of seniors he will do his work honestly and later his works will serve as a sample for other generations.

Here it is important to add that a person making an icon must understand what occurs on the Liturgy. An artist having decided to make an icon and not understanding the liturgy is something abnormal. It seems to me, that the connection between the ancient and modern icon is based on the following the canon and transferring the Orthodox doctrines.

Pageau– Cast icons being relief icons, the image of the Holy person is traced in shadow rather than in color and light as in painted icons. As an icon carver myself, I have always been particularly sensitive to this facing the theology of light which usually infuses discussions on iconography. In your work this emphasis on a certain darkness and opacity seems to be even accentuated by the unpolished and direct presentation of the material. In some cases you even use oxidation, which is properly speaking a kind of decay, to create contrast. How, in your view, does this tracing in shadow and presence of the material speak to the theology of the icon?

Aleksejevas– Sculptures and pictures, as a means of expression, differ very much one from another. These are two different languages. The details that in a hand-written icon can be depicted with the help of color, in a relief are shown by means of plans reflecting light with different intensity. The deepest and darkest places of a relief help to emphasize the forefront which is closer to viewers. A dark place in a relief is not an equivalent of a shadow; it is rather a way to show the structure of form. Shadows are never molded, and patches of light on bronze are “freshenings”, made with special substance for covering. Light theology is present in a relief icon but it is expressed differently than in a hand-written icon. I like the statement: darkness does not exist; it is only the absence of light.

Pageau– Since relief icons were somewhat forgotten until the last decades, what has been the reaction to your works? How do people react?

Aleksejevas– Differently. Sometimes they react with interest, sometimes remain indifferent, and sometimes even negatively. Recently one architect-sculptor was indignant – how in an icon the head is big and the hands are small? I tried to explain what the return prospect in an icon was, but unsuccessfully… He considered that it was something primitive having come from the Middle Ages.

Others with whom I have been communicating for a long time and who know my works react with pleasure and interest.

The majority of people don’t perceive my icons as icons at all. For them it is a secular art on religious subject. And it is logical because only few of them faced a bronze icon in real life.

Parishioners of church often treat a bronze icon watchfully. Probably, it is because such icons had been prohibited and pursued for nearly 200 years.

My icons as pieces of iconography with all its nuances and features are generally treated by my colleagues and pupils. They are few.

Pageau– Your icon work seems to have developed at least partly in relation to the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts. We know two of our collaborators, Christabel Anderson and Aidan Hart are also connected to that school. In North America we are curious and fascinated by such an institution as we have nothing comparable. Can you tell us a bit about your involvement with school?

Aleksejevas- I have been being connected with this school for 5 years. I have learned about it from an iconographer, Doctor Stephane Rene.

One of my exhibitions was held in London, in the gallery Sacred Space where Stephane is director. He helped me to get acquainted with this school and to become interested in an opportunity to study and to write a scientific work on bronze iconography. I am very glad that the destiny has brought me to this school. I have been already studying this subject for some years, generally the Old Belief iconography almost unknown in the West. I study the reasons of its emergence, its history and various factors influencing the development of this tradition. These are economy, religion, politics, theology and many other things.

PSTA gives a unique opportunity to make PhD by project. Thus at once all my theoretical finds turn into practice, into my bronze icons.

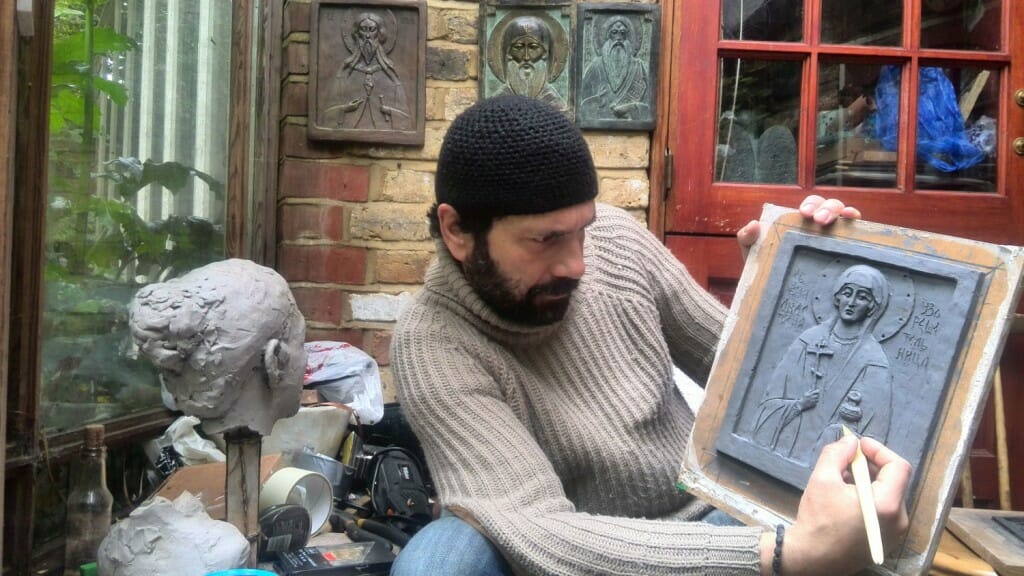

Pageau– What are the basic steps you go through in creating a bronze icon?

Aleksejevas– Usually I begin working on a new icon with searching for the prototypes of the image. I study the history of this image, and then I go deeper studying the sacred life or interpretations and explanations of the texts concerning this subject. The first stage of work is theoretical. Then I determine the size and I choose material for modeling. Usually it is plasticine. Then the process of modeling which can last for some days, some weeks or even some months begins. When the relief is ready, I take a plaster or a silicone mould from it and transfer the relief to a wax model in bronze. This technology is called lost wax; it is well-known among the experts-founders. I process, stamp, grind, polish if it is necessary, and then patinate the cast icons. Usually I do patina myself; I have old, checked recipes which I like. A ready bronze icon is very durable, it can exist for centuries, and therefore it was loved by the Old Believers.

Pageau– The icons in the series we usually see are portable size. Do you hope to work on bigger surfaces, doors maybe? What about more complex subjects like festal icons?

Aleksejevas– Yes, it is true; my icons are of small size, transportable or made for lecterns. There are several reasons for it. Work with big items in bronze requires a big workshop, a lot of place for modeling and storing forms and materials, huge financial expenses are also necessary. Now I have no such opportunities and conditions, whereas, the size in which I work allows solving all iconographic problems “with small losses”.

Of course, it would be interesting to make bronze gates, to work with an iconostasis or to make a bell with reliefs. I have such an experience but rather with casting, than with sculpting. When working in Moscow, I participated in a grandiose project of production of three church gates devoted to the theme of the Great Feasts for the temple of the Life-giving Trinity on Kashira Highway. The height of each gate was 5.5 meters. My friend, Moscow sculptor Dmitry Uspensky, was the author of the project. I was busy with casting and everything that was connected with technical aspects of this project and, of course, I learned much during this time.

Such monumental works differ very much from working with small sizes. Everything, from beginning to end, is based on other principles.

Recently, for a “warm-up” I designed a project of bronze doors for one church. Meanwhile it remains in my notebook but who knows, maybe sometimes…

As for more complicated works, in the nearest future I plan to make all the Great Feasts. Recently, in St. Afanasy monastery in Greece I saw a very interesting iconostasis with beautiful icons in the Macedonian style. I managed to take a photograph of it and I hope that it will serve as a prototype for the future series of festive icons.

A few links to explore more of his work.

At Prince’s School. http://www.psta.org.uk/postgraduateprogramme/currentresearchstudents/theartofthebronzerelieficonhistorymeaningandmaking/

Secular work: http://www.hayhill.com/docs/aleksejevas.html

Thank you Jonathan, for the interview. And thank you Orthodox Arts Journal, Andrew Gould, for these wonderful continuing treasures. The work of Alex Aleksejevas is moving and changes my perception / understanding of our sacred art. His story is inspires me. His work, even more. The Prince’s School is doing some wonderful work. How wonderful to have a place for a PhD study in this.

I have been reading the Orthodox Arts Journal for a couple of years now, thanks to Fr. Antonio Perdomo and Matushka Elizabeth Perdomo here in Pharr, Texas for introducing it to me. The articles have always interested me. In fact, I just returned home to Texas yesterday, from a trip to Holy Ascension Orthodox Church in South Carolina, to attend the Iconography Symposium organized by Andrew Gould. These programs (I have also studied with the wonderful Hexaemeron program, which I see is endorsed here) help me greatly as an Orthodox Iconographer. At this point, they are currently helping me in my graduate work towards an MFA degree here at my local University (University of Texas Pan-American) that is situated on the boarder of Mexico. My MFA thesis (“by coincidence”) that was approved well before I got word of the Symposium, explores exactly what the Iconography Symposium was about ~ the visual implications of up-holing an ancient tradition in our contemporary times. Knowing that synchronicity is a gift, I flew out to South Carolina to attend this Symposium and it was well worth it. I am so grateful for all these opportunities and that I was able to attend; it was a life changing experience in a positive way. I am beginning to understand my purpose.

The synchronicity I find through OJA is happening again now after reading this article. My (undergraduate) BFA was in Metal Fabrication (bronze casting). I was assistant to Civic Monument Sculptors Raymond Kaskey and Arturo Di Modica, helping the maestros create “Charging Bull” (NYC, Wall St Park) and “Wisdom & Courage” (Santa Anna California, Ronald Regan Courthouse) bronze cast monuments. Alex Aleksejevas’ work makes sense to me. The bronze casting work didn’t appear to have a place for me, in my understanding of the Icon, until just now, even though I worked as an Art Handler, with the magnificent collection of Icons (in egg tempera and in ivory relief) and Byzantine Manuscripts for 7 years at The Walters Art Museum. And so this being part of my journey naturally opens my mind and heart to another solution. So it is with deep gratitude I write, just to give thanks for helping me learn and grow along the way. I have been thirsting for this type of learning, for so many years and give thanks it is being revealed yet again.

Many many thanks ,for all that all of you, for the Glory of God.

These sculptures are yet another wonderful example of traditional, canonical art made fresh and new again. Especially interesting is the presence of overt influence from modernist 20th-century sculpture – the use of deliberate unrefinement and primitive/childish details, such as the lettering in the inscriptions. We normally think of modernist influence as being a great danger to sacred art (and very often it is), but these sculptures really work – they are truly prayerful icons. This goes to show that the tradition is resilient enough to handle foreign influences, and can baptize even the most ‘fallen’ of styles.

Is it fair to say that folk art (or the influence thereof) is typically characterized by an enlargement of details (facial features, lettering, facial expression) that would normally want precision execution but that must be crafted using un-precise/larger tools and/or in a medium that does not receive detail well?

This seems to me to be a binding link that ties folk arts of various cultures together around the world. I haven’t heard it expressed before but probably y’all who went to art school know the answer to this.

Thank you for this very interesting article on the bronze ikons of Aleksejevas. Aciu!

But there are 8, not one, bronze icon door in Italy, that are described in the article here below:

http://www.academia.edu/7266932/Le_porte_bronzee_bizantine_in_Italia_arte_e_tecnologia_nel_Mediterraneo_medievale