Similar Posts

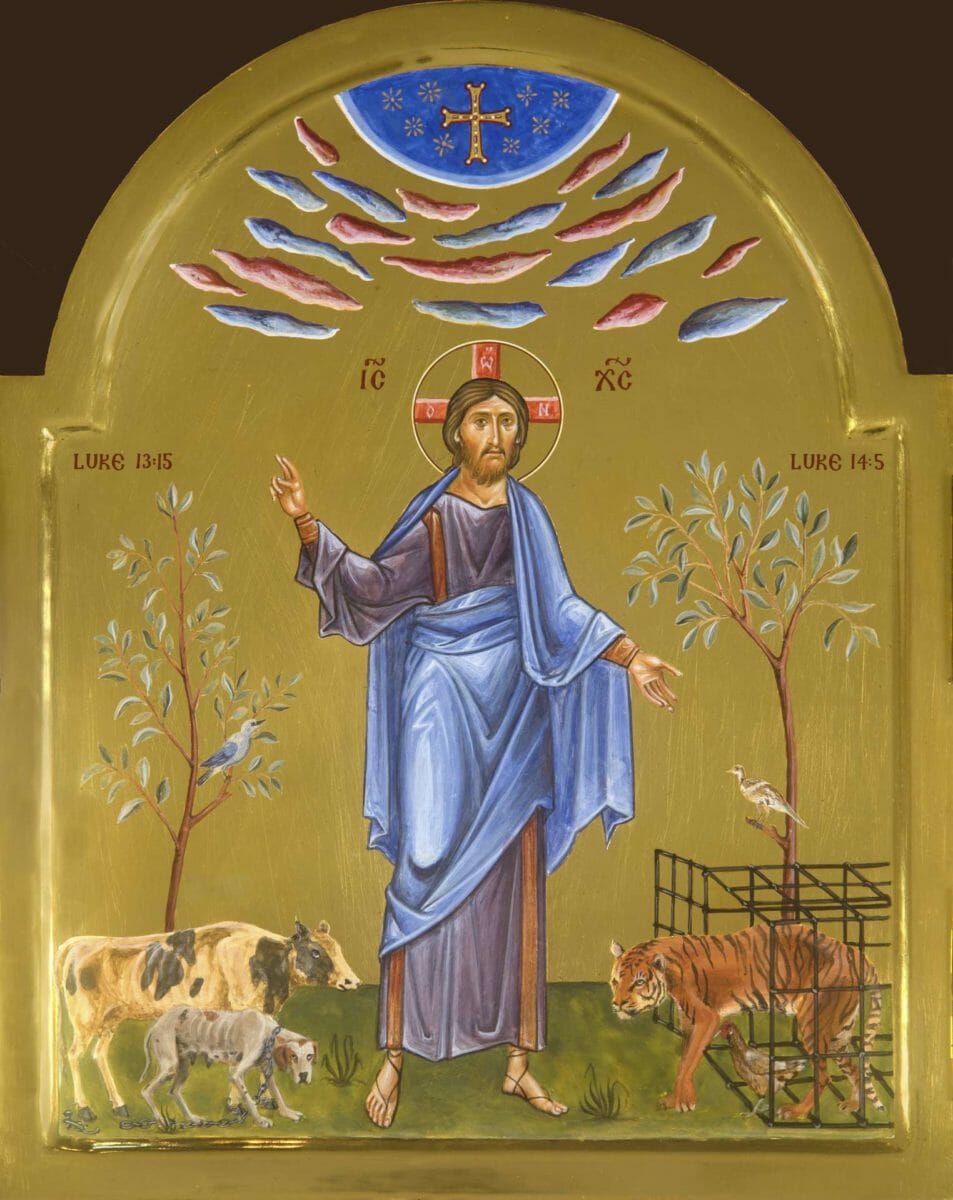

Sometimes I am commissioned to paint an icon of a saint for whom nothing yet exists, or at least no satisfactory icon. This is usually a pre-schism Western saint. But more rarely, the subject is a new theme, a new emphasis or combination. This was the case when Dr Christine Nellist approached me to create an icon that embodied some of the Orthodox Church’s teaching about our relationship with animals. The icon was to be used as flagship for her newly founded organisation “Pan-Orthodox Concern for Animals” (http://www.panorthodoxconcernforanimals.org/) and to illustrate her pending book on the subject. This article tells the story of its genesis and explains its design.

The brief was for the icon to affirm the need to love all creation, but especially to treat our fellow animals with the respect and kindness due to all God’s creatures. It had to show that Christ came not just to redeem humankind from the fall, but also, through our repentance, to deliver the animal kingdom from our oppressive and cruel treatment of them. As Saint Paul wrote to the Romans:

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God . . . because the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God’. (Romans 8: 19, 21)

The icon you see illustrated is what we eventually created. It required both theological enquiry and research into past iconography, so I would like outline how these two came together.

The Bible and animals: the beginning, middle and end

The Bible narrative begins and ends with lots of animals. The creation account in Genesis teems with them. One whole day is dedicated to the creation of just the water creatures and the birds, and another to the creation of land animals and humankind. God liked what He made, declared it good, and blessed the creatures to multiply and fill the earth.

God breathing life into Adam and creating the animals. Mosaic from the Palatine Chapel, Palermo, Sicily, 12th century.

The last book of the Scriptures – Revelation – ends with a description of the New Jerusalem, the holy mountain coming down out of heaven from God. Although the Evangelist John himself does not include animals in his description of this New Jerusalem, the prophet Isaiah certainly does. In just three verses Isaiah names thirteen different animal species to be found on the Holy Mountain:

6The wolf shall dwell with the lamb,

and the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

and the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

and a little child shall lead them.

7 The cow and the bear shall feed;

their young shall lie down together;

and the lion shall eat straw like the ox.

8 The sucking child shall play over the hole of the asp,

and the weaned child shall put his hand on the adder’s den.

9 They shall not hurt or destroy

in all my holy mountain;

for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord

as the waters cover the sea. (Isaiah 11:6-9)

Between this beginning and this end the Bible of course refers to animals many other times. But as a consequence of the fall our relationship with the animal kingdom is far from what is described of Eden and the New Jerusalem. Into the midst of this man-made mess comes Christ. The turning point of history is the incarnation of God in Christ. The focus of this has naturally been the redemption of the human race. But because we live in this world and we are supposed to be earth’s carers, this redemption implicitly involves our relationship with animals.

Unsurprisingly, the icon of Christ’s Nativity depicts animals: an ox and an ass in the manger, and sheep with their shepherds. These creatures play an important role in the icon’s depiction of the divine drama. Of all the created beings in the icon, it is the ox and the ass that sit closest to the Christ Child. These two animals are included not just because Christ was born in a manger, but also to illustrate Isaiah’s prophecy:

The ox knows its owner,

And the donkey its master’s crib;

but Israel does not know,

my people do not understand. (Isaiah 1:3)

Both the icon and the Orthodox liturgical texts for the Nativity suggest that at the incarnation God began to restore paradise, and thus to heal the broken relationship between God, man and animals:

Bethlehem has opened Eden; come and let us see. We have found joy in secret: come, let us take possession of the paradise that is within the cave. There the unwatered root has appeared. (Ikos, Canon of Matins)

Some commentators say that the ox and the ass stand close to the Christ Child not just because they recognize their Creator, but also because they are warming the Christ Child with their breath! According to the creation account in Genesis, animals are helpmates for us, and here they are being just that.

It is surely significant that of all the Jewish people God chose shepherds to receive the revelation and to greet the new-born Child. A shepherd cares for his sheep, knows them all by name, and will even risk his life to protect them. It is perhaps this nurturing relationship with God’s lesser creatures that prepared the shepherds to receive the astounding news of Christ’s birth. God even invited them directly through angels, and not through a dumb and distant star as He did for the worldly wise Magi.

So, in one way or another, our destiny as humans seems linked to animals. God created us on the same day that He created the animals, so you could say that we are neighbours, and indeed, that we are related.

The icon’s design

In the Orthodox Church, icons are images of people or sacred events to be venerated. Icons are, in the fullest sense of the word, personal, and not just a cerebral illustration of an idea or a system. So Christine and I didn’t want the triptych to be merely a didactic tool. It had to be an icon of a person or sacred event that could be venerated in church. September 1st provided a liturgical celebration that is directly concerned with creation. This day was established by Patriarch Dimitrios I as an official commemoration of prayer for all creation. So this set the liturgical scene for such an icon. It could be legitimately used for veneration in church on that day.

There was also the feast of the Resurrection. Christine had originally suggested that the triptych could be a variation of the Resurrection icon, with Christ delivering not just people from the bonds of Hades but also animals. But this was problematic. It would have raised the thorny, and ultimately unanswerable, question of whether or not animals had eternal souls. It would have based the case for non-cruelty to animals on the answer, and therefore undermining it if the viewer believed animals to be soulless.

The argument had to be more secure: animals are to be cared for simply because God created them, soul or no soul. Full stop.

But we still wanted to show Christ actively liberating animals from cruelty. The Resurrection icon remained an obvious starting point, but the design had to be more subtle than simply adding animals to the dark abyss of Hades.

So the challenge remained how to express Christ’s redemption of animals from cruelty and oppression without the icon merely illustrating an idea – albeit a very important one. I decided to set our relationship with animals in the context of God’s intention for humankind by signifying the three principal “epochs” described above: Paradise, the incarnation, and the New Jerusalem. Why such a grand scope?

Paradise and the Incarnation

We write the story of history with our deeds. If we have ‘lost the plot’ in our relationship both with God and with the rest of creation it is because we have forgotten our story’s beginning, middle and end. “Where there is no vision, the people perish”, we read in Proverbs 29:18. In these three nodes of history God is the writer and the initiator. But it is we who write what happens in between. We can write our lives either contrary to or in alignment with God’s intention. To retell the full story in one image was of course impossible, but the icon could at least hint at these three points in the economy of salvation and thus help to set us back on the right plot.

How does the triptych express these key epochs in the divine-human story? The icon suggests Paradise by the inclusion of trees, sea, grass, bees, birds, fish, snake and lizard, all of which look healthy.

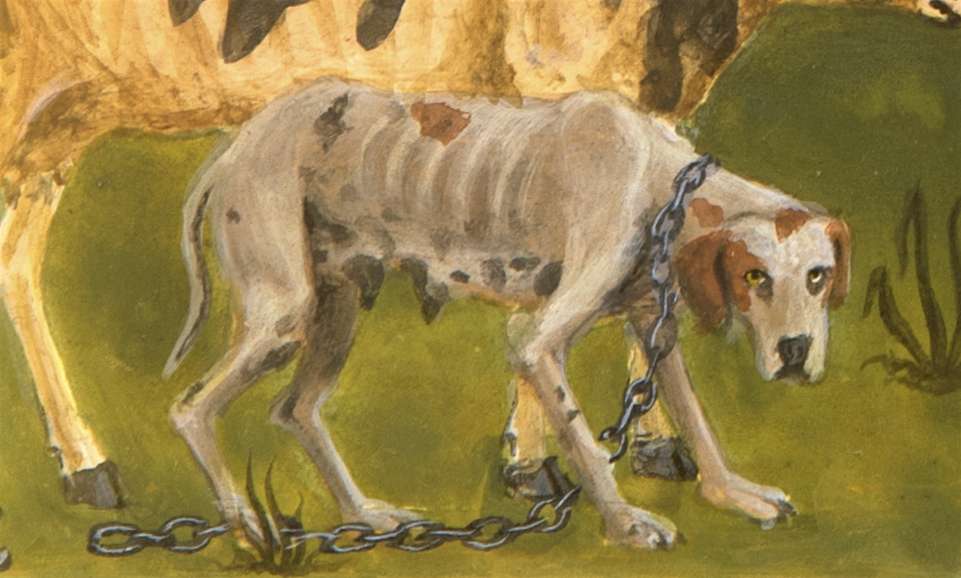

These creatures, and Saints Irenaeus and Isaac, face or move towards Christ, acknowledging Him as their Creator and Sustainer. By looking out at us, the dog draws us into the event, as though inviting us to partake of this liberation. This attitude of praise and thanksgiving lies at the heart of Edenic life, just as ingratitude lies at the heart of a hellish life.

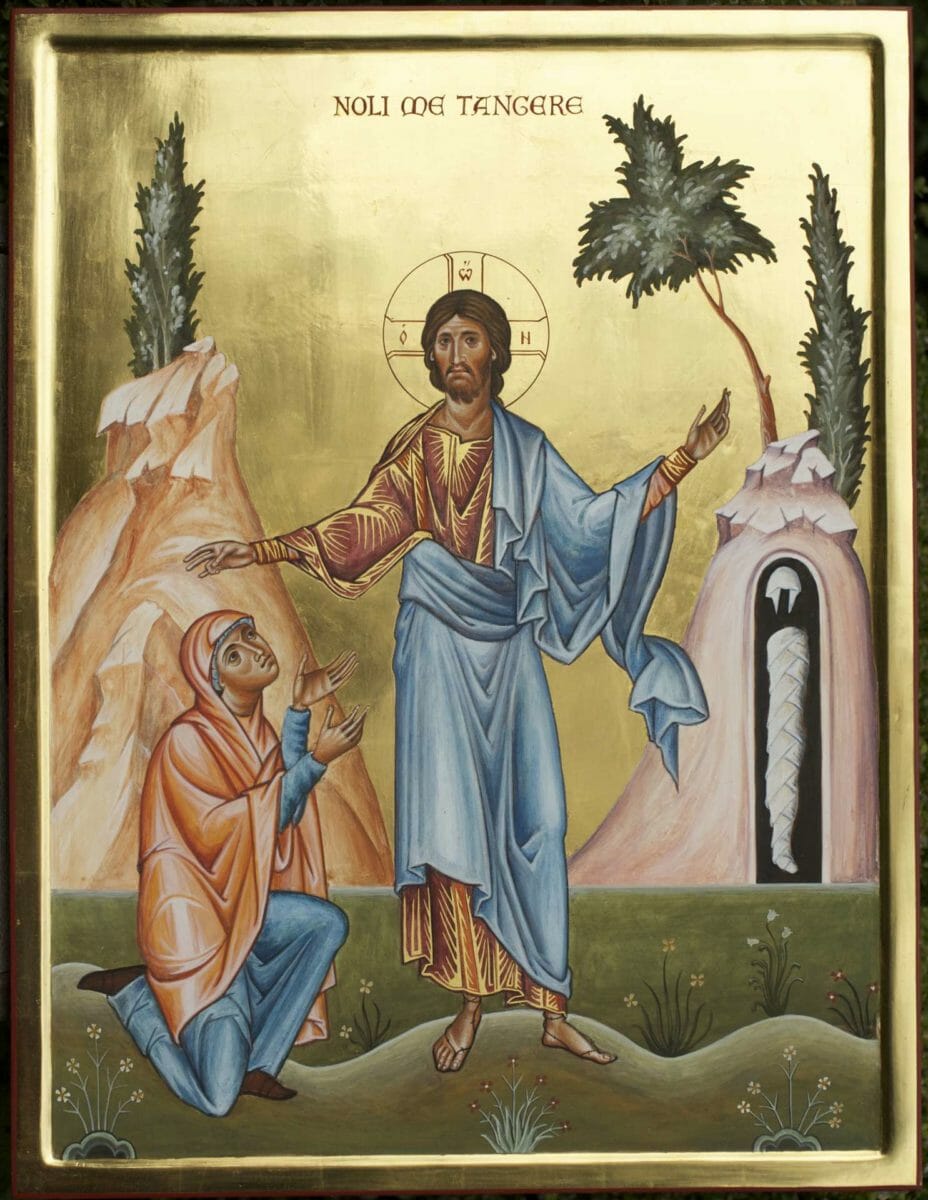

Sometimes the Bible describes a blunder that proves to be a prophecy. Such is the case when Mary Magdalene mistook the risen Christ for a gardener.

He is in fact the archetypal gardener, the second Adam who nurtures creation, tilling and keeping it with love and reverence in a way that the first Adam failed to do. This triptych shows Christ in the midst of creation, like a second Adam in paradise. He blesses with it His right hand, and directs it with His left. He is the prophet, priest and king of creation.

What of the predicament of our current age? The icon depicts the tiger, cow and dog as emaciated, victims of human neglect. But it also shows Christ blessing and liberating them, the tiger and chicken from their cages and the dog from its chains. Christ has come to set not just humanity free, but all creation.

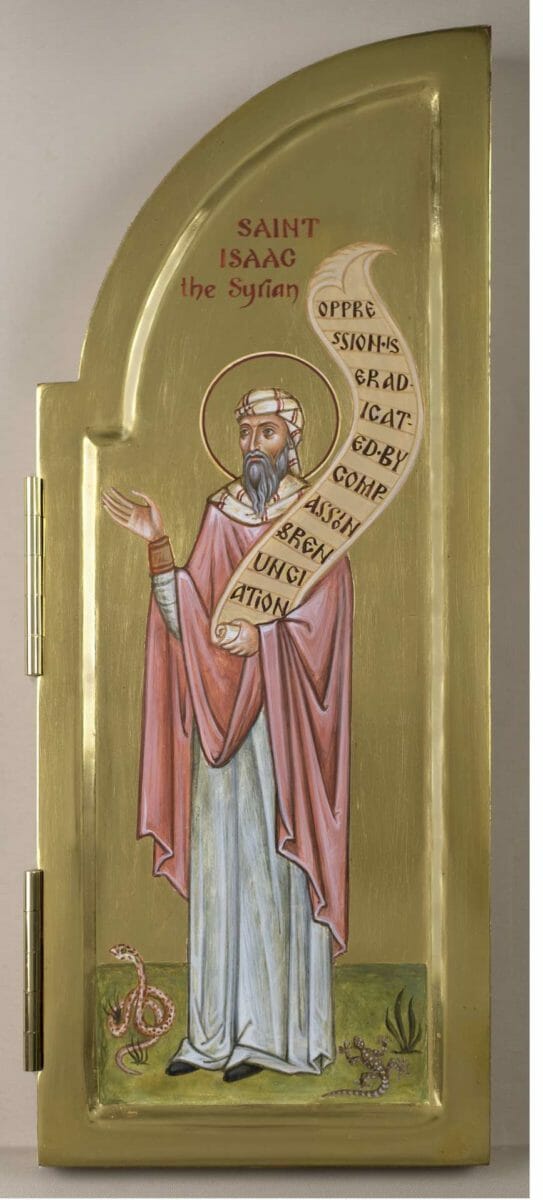

The quote on Saint Isaac the Syrian’s scroll suggests that oppression of animals is the result of lack of compassion, lack of virtue: “Oppression is eradicated by compassion and renunciation.” The compassion that makes us feel for our fellow humans is the same virtue that impels us to empathise with the suffering of a fellow animal. Although we humans are more than just animals, we are at least animals. In our physicality we are related to the animal kingdom. To mistreat them is by extension to mistreat ourselves.

All this is not to say that the icon is promoting vegetarianism. But it is asserting that cruelty to animals is contrary to God’s intention; that we are to care for them and respect them, even when our survival requires killing them for food. I was very impressed by a documentary I once saw that followed the life of some traditional African San bush people. The men were hunting a gazelle, the main source of food for their tribe. They had only spears, so the only way to kill it was to chase it on foot for many miles, until at last it had to stop and surrender, exhausted. Before killing it, the one hunter who had managed to endure the marathon up to this point spent time to give thanks to the animal for offering itself. There had been a struggle of equal strength, and this time the hunters had won. Other times they would lose. The bushman thus believed that he was not taking the gazelle’s life but receiving it. The gazelle was offering itself for the sake of his life and his family’s life.

Care for animals in our charge is a theme of the Gospel passages whose references are inscribed in the central panel:

Then the Lord answered him, “You hypocrites! Does not each of you on the sabbath untie his ox or his ass from the manger, and lead it away to water it?”

(Luke 13:15)

And he said to them, “Which of you, having a son or an ox that has fallen into a well, will not immediately pull him out on a sabbath day?”

(Luke 14:5. NOTE: Other ancient authorities read an ass instead of a son)

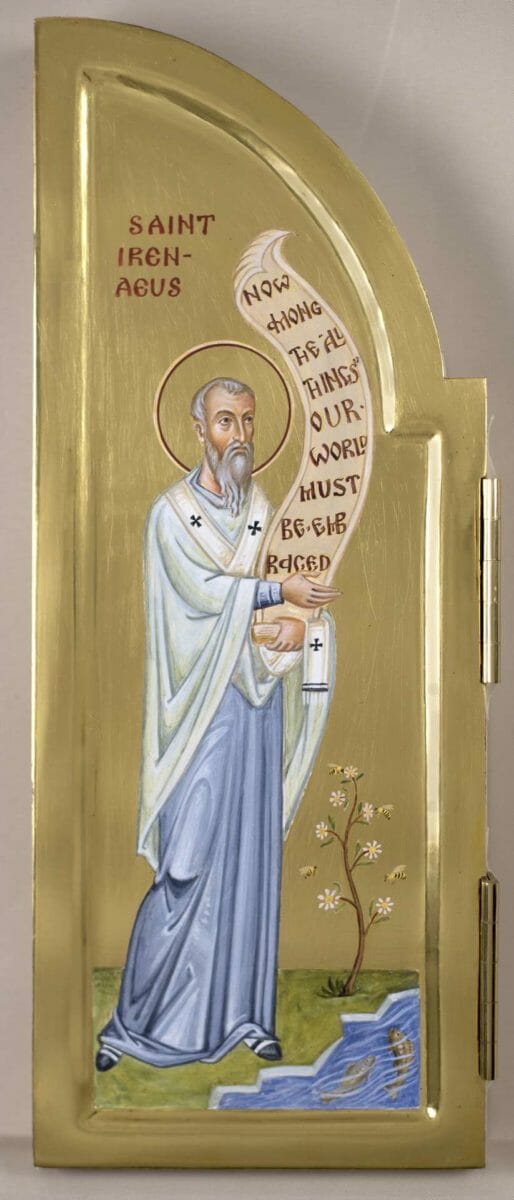

Saint Irenaeus’ quote on the left wing continues this theme of Christian love and kindness towards all God’s creation: “Now, among the ‘all things’ our world must be embraced.” By itself this text is somewhat opaque. It makes more sense in its context, even in the somewhat antiquated 19th century translation found in the Ante-Nicene Fathers series:

…as John, the disciple of the Lord, declares regarding Him: ‘All things were made by Him, and without Him was nothing made’ [John 1;3]. Now, among the ‘all things’ our world must be embraced. It too, therefore, was made by His Word, as Scripture tells us in the book of Genesis that He made all things connected with our world by His Word.

(Against Heresies, Book 2, II:5,6) [1]

St Irenaeus is telling us that all things are made by God, from stone to animal to angel, and as such are to be honoured. He was countering a Gnostic heresy current in his time, which asserted that the material world was not created by God but by a demi-god, and that it entrapped the soul. Irenaeus refutes this by showing from the Scriptures that the universe is created by God, and is a means of union and communion with Him and not an impediment. Although it would be difficult today to find many people who adhered to Gnosticism in this raw sense, surely a Christian is not far from this heresy when he or she lives as though the animal kingdom were of no consequence to their spiritual life, apart from being a source of food.

One element of Christ’s Nativity that the Church’s liturgical texts emphasize is that the incarnation inspires all creation to offer Him thanks. The Incarnation initiates the beginning of a new creation. In this renewed paradisical life creatures receive life with thanksgiving, instead of grabbing it and turning from God as did Adam and Eve. Each thing and being offers thanks according to its nature. As a hymn of Vespers so beautifully puts it:

What shall we offer you, O Christ, because you have appeared on earth as a man for our sakes? For each of the creatures made by you offers you its thanks: the Angels their hymn; the heavens the Star; the Shepherds their wonder; the Magi their gifts; the earth the Cave; the desert the Manger; but we a Virgin Mother. God before the ages, have mercy on us.

(Great Vespers of Christmas. Translation by Archimandrite Ephraim Lash)

In the icon not only do the Edenic creatures face Christ, but also the liberated cow, dog, chicken and tiger. Christ frees them not just from physical oppression, but also so that they can attain their fullness as participants in the cosmic liturgy of praise.

Just as a sunflower turns its head throughout the day to follow the sun, so all creatures are created to live in adoration of their Creator, each according to their nature. Cruelty to animals therefore not only causes physical suffering to the victims but also introduces a tragic dissonance to this cosmic hymn. Such behaviour is a sin not only against the animals, but is also a failure of us humans to be conductors of the eucharistic choir.

When we separate our treatment of animals from our worship we are like the priest and the Levite in the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37). When they saw the man beaten up by robbers, in their haste to worship in the temple they crossed to the other side of the road to avoid caring for him. I wonder if God accepted their worship when they reached the temple?

The last three Psalms of the Bible, collectively called the Praises or Lauds, are sung at the end of every Matins service. They are the culmination of all that has gone before and, together with the Doxology “Glory to God in the highest”, are the precursor to the Holy Liturgy or Eucharist that follows:

1Praise the Lord!

Praise the Lord from the heavens,

praise him in the heights!…

7Praise the Lord from the earth,

you sea monsters and all deeps,

8 fire and hail, snow and frost,

stormy wind fulfilling his command!

9 Mountains and all hills,

fruit trees and all cedars!

10 Beasts and all cattle,

creeping things and flying birds!

11 Kings of the earth and all peoples,

princes and all rulers of the earth!

12 Young men and maidens together,

old men and children! …..

(Psalm 148:1, 7-12)

This is not just a call for us humans to praise God, but also all creatures, and even the inanimate kingdom. Our destiny and calling is inexplicably tied up with all creation.

Christ’s Second Coming and the New Jerusalem

We have discussed how our triptych hints at Paradise and Christ’s incarnation and resurrection. What of His Second Coming and the New Jerusalem?

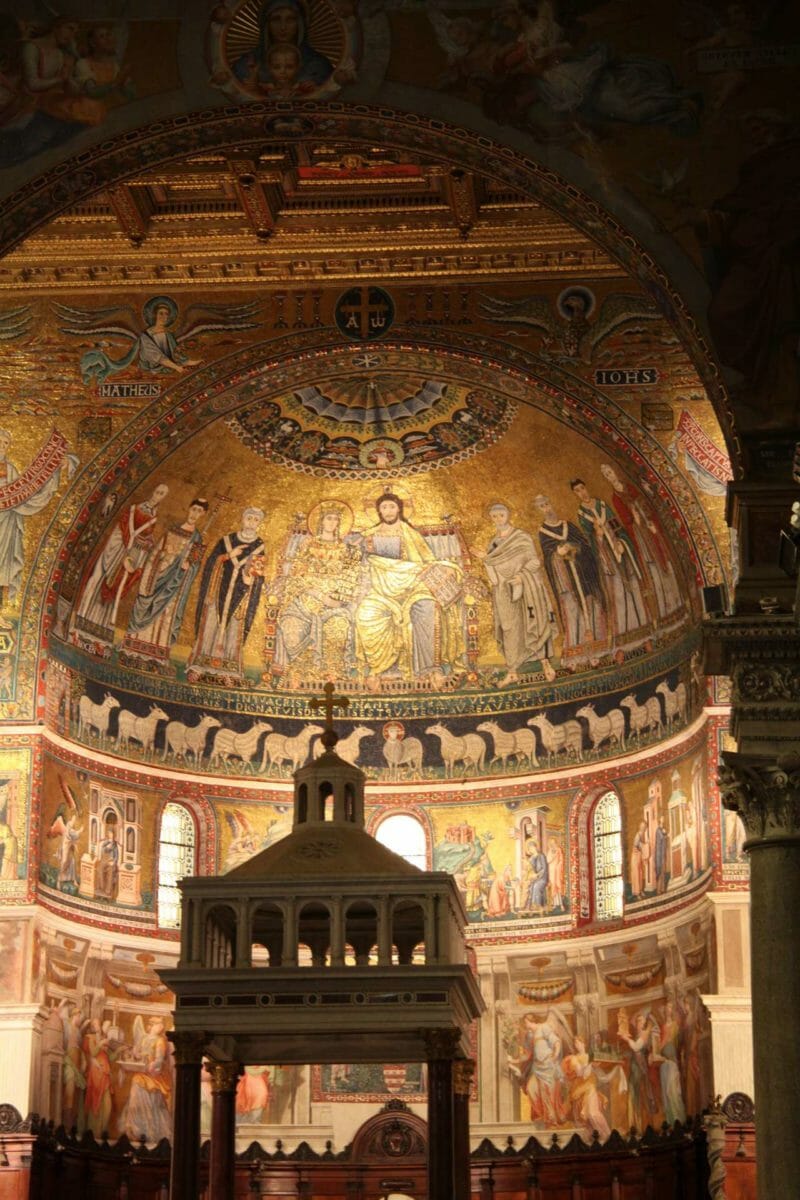

Roman mosaics offered a solution when I was looking for ideas. Rome is home to numerous apse mosaics dating from the first millennium. Some of them show Christ in the midst of brightly coloured clouds. Examples are found in the churches of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Santi Cosma e Damiano, Santa Constanza, Santa Prassede, and Santa Maria Trastevere.

What do these clouds represent? They are clouds of a sunrise, and thus indicate Christ’s Second Coming in glory:

…then will appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn, and they will see the Son of man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory… (Matthew 24:30)

Most of these apses also bear a cross at the apex. This is the “sign of the Son of Man” that will appear in the skies at Christ’s coming, a sign traditionally understood by the Orthodox Church to be the cross. The stars that surround our cross in the triptych represent the host of heavenly angels that will accompany Him.

Why should we include the theme of the future New Jerusalem in an icon about animals? Churches traditionally face east, towards the rising sun, towards Christ’s coming again in glory. Consciously or unconsciously, every individual and every culture lives the present in the light of their belief about the future. When driving a car, we tend to steer in the direction we are looking. Our actions tend to follow our gaze, follow our vision of the ideal.

John’s description of the New Jerusalem is highly symbolic, and is not intended to provide lots of detail to be taken literally. But the essence of what he is saying is that God will be pleased to dwell among us, because all His creatures will be living in harmony with one another. There will be no sin or cruelty, and therefore no death, crying or pain.

We do not know for certain what place animals will have in this community of the New Jerusalem, but if we are to take at face value Isaiah’s words quoted at the beginning of this article, there will be lots of them and we will all live in unity. If the destiny of human and beast is not to “hurt or destroy in all God’s holy mountain”, why not begin to live like this now, inasmuch as it is possible? Hopefully this little icon will help a few of us to begin.

[1] (Against Heresies, Book 2, II:5,6, translation in “Against Heresies, by Irenaeus, ed. Philip Schaff, Eerdmans, 1885. Page 85 in Woodstock, Ontario, 2017 edition.

I’ve recently been reading Ask the Beasts: Darwin and the God of Love by Elizabeth Johnson. This article is remarkably similar. Good things are happening on our Planet despite the apparent clouded darkness. Great article.

Very nice. I was skeptical at first. I am an animal lover but a convinced traditionalist as well. Glory to God.

This is a beautiful work and I applaud the chosen topic! Hosea 2:18: “In that day I will make a covenant for them with the beasts of the field and the birds of the air and the creatures that move along the ground. Bow and sword and battle I will abolish from the land, so that all may lie down in safety.” If God has made a covenant with the animals, no one will ever convince me they are soulless and incapable of eternity in Heaven.

Thank you for reminding me of this passage from Hosea – perfect apt!

Sorry, I am not convinced. I can sympathize with the theme but not the extreme emotion-provoking presentation of the animals on the icon. I think the way their expressions are rendered will take a viewer far away from an attitude of veneration to one of anger.

Designing this commission to “advertise” a new ministry seems slightly akin to having a point in mind for a sermon, then searching for verses to back up the point you’ve already decided to make.

You make a valid point, but the history of iconography is chock-full of examples of patrons choosing subject matter to promote their political agenda. This includes the many of the beloved mosaics in Ravenna, which have overtly royalist themes and illustrations of contemporary court life. It may sound problematic, but it’s not that different from monasteries promoting their agenda by emphasizing pro-monastic figures like St. Gregory Palamas.

Even when it comes to painting ordinary parish churches, I happen to know that artistic diversity emerges largely because priests request subject matter that promotes their theological ‘pet’ interests. I don’t see anything wrong with this, because otherwise, we’d just be painting everything exactly the same. It seems to me that developing new icon compositions that speak to contemporary concerns is one of the most natural ways for iconography to remain a living art. But as with any new icon, it will take time for the church to decide whether to accept this image as helpful, and paint more versions of it, or to leave it obscure and at the margin of the tradition.

Hello Michael. Thank you for your response. A new icon like this is always going to be a work in progress, so frank reactions are very welcome. I agree with you, that the animals could have been rendered better. If I could paint the icon again I would do them less naturalistically – still being released from some form of bondage, but without the extreme emotion. Having said that, there are some examples of traditional icons where people are expressing very strong emotion, such as the Mother of God (and sometimes the other Marys) in the Crucifixion and in the Deposition.

Although the newness of the theme does run the risk of making the icon appear as an advertisement, I have to disagree with your point about an icon being used to “back up” a theological assertion. Surely all the festal icons do just this, interpreting and elucidating a truth also expressed in the Church’s hymnography and writings? Such icons do not merely repeat, but, being a different medium from the word, can offer distinct insights on a sacred event, or at least, touch a different part of our being than can words.

Andrew Gould, I’ve long ago noticed that you can not make a difference between the icon as a sacred object and the wall painting that has no such qualities. You arbitrarily mingle topics that have no place in true icon painting.

And what is your evidence that there actually exists such a difference? Where, in the historical record, can you find an argument that icons are sacred objects and that wall paintings are not? On both you will find paintings of saints, and on both you will find paintings of non-saints. Both are called hagiography by the Greeks. I have seen all sorts of strange things on antique panel icons that it is hard to imagine venerating (angels of the apocalypse, Holy Wisdom, the Magi, demons pulling monks off the Ladder of Divine Ascent). So who is to say that the tradition requires panel icons to depict only sacred subjects that one can venerate?

Not that that’s specifically an issue with Aidan’s icon here. It is clearly conceived as a sacred object where the figure of Christ can be venerated. I’m just saying that despite the assertions of certain 20th-century iconologists, the historical record does not really support the idea that panel icons are held to a different standard of subject matter than wall painting.

I agree with Andrew. On Mount Athos we would often venerate wall pantings of saints (those low enough to reach!). Although it is true that the emphasis of wall paintings is different, this does not render them as not sacred, and worthy of veneration. What makes an icon an icon is not the medium, place, or even style necessarily, but that it bears the name of the sacred person.

In ecumenical spirit I recommend the poem ‘A Legend’s Carol’ by Francis Warner, inspired by a disagreement with C.S. Lewis over a passage in Plutarch where the death of Pan after the birth of Christ is discussed. I also recommend John Piper’s nativity window in Magdalen College Chapel. Both sprang to mind after reading this beautiful and thought-provoking piece.

I really wonder if we do need such an icon.

Especially the fact that its been commissioned by Constantinople makes me extremely weary about the spirit which animates it.

Certainly, Christ’s action is cosmic, universal in scope and God’s providence watches over every single creature, there is no argument in that. You also have Ps. 35 where it says that God will save man and beast and also in Solomon’s Proverbs (chapter 11 or 12) it says that the righteous man has mercy for his cattle.

So there is no argument in that.

However, we live today in a context when man’s love for his fellow man is growing cold and he is trying to compensate this for an exaggerated love for animals. I see more and more people who are almost indifferent to human suffering, but devote themselves to animal suffering. This is just one more sign of the times and the disorder in which we live. We are incapable of loving each other so we try to compensate by loving animals in a pathological way.

In this sense, I am very skeptical about this kind of theme. I don’t think that it is something we need.

This is very reasonable concern. While this icon serves a unique purpose for the organization that commissioned it, I too would be concerned if it became a ‘mainstream’ icon seen in other contexts. If that happened, its popularity could indeed be seen as a symptom of the contemporary pathology you describe.

Thank you, Mihai, for taking the time to reply. Putting aside whether or not the icon design itself is successful – I fully acknowledge its weaknesses – I don’t quite see the logic of your argument. First, what has Constantinople got to do with the subject at hand? Do you think only bad comes from this Patriarchate?

Secondly, your point about compensation. Indeed, some animal activists do get their priorities wrong, hating humankind and loving animals. But this is precisely what the theology behind the icon is trying to counter: it tries to place care for animals in the context of love for Christ their creator, and away from sentimentality, political agendas, or mere cultural preferences. Whether or not the icons works is another point, but its design is distinct from the theology that underpins it.

Our response to the problem of the love of man growing cold should not be to reduce care for all creatures, as though we have a limited amount of love. In fact, at least as children, we often learn proper behaviour towards people by first learning to treat the lesser creatures well. If a child learns that to kick cats is acceptable, they are surely more likely to mistreat humans? The only enduring basis for love of all creatures is that God created them. Saints such as St Paissius of Athos, with whom I spent time on a number of occasions, show us this by their gentleness towards all creatures – human and animals. The form of expression will vary depending on the creature, but the impulse is the same: to love God through love of his Creatures as well as through prayer and worship. Natural theology (perceiving God in all created things) is precursor to mystical theology.

I read with great interest your article and learned a lot from your explication. I offer some thoughts on the project.

Perhaps the triptych was not the better format. I have a vast collection of photographs of icons on my computer and I recalled having seen a contemporary icon from the creation narrative which covered the creation of the birds of the air and the beasts of the field. Indeed, representations of the animal kingdom are all over the image (you need more animals–lots more). This icon falls into a category of icons which I have been informed are properly called “didactic” or teaching icons and, as such, are not usually venerated. The well known icon of the Ladder of Divine Ascent is such an icon. Even though a tiny image of Christ God is way up in the corner (the presence of divine personages being otherwise worthy of veneration) exception is made for teaching icons. Thus, the icon of the Ladder is not venerated, particularly since icons of St. John Climacus are readily available.

There are, nevertheless, wonderful icons on single panels which illustrate not only a particular saint, centrally placed, but mini icons which surround the central image, which illustrate and teach about events in the saints life.

I say all this because I suggest the triptych format is more likely identified with sacred personages and them only. Perhaps a better format would have been the panel where several “supporting” factors such as images of saints with scrolls which attest to the singular importance of the central creation event could be included.

Having said all this, especially about the non-veneration of teaching icons, I can’t help but wonder how I might somehow “venerate” an event such as the creation which is undeniably sacred, coming as it does from the Lord of Creation and Him alone.

Forgive me if I ask for a moment more of your time to address another issue which arose in the comments and that has to do with the relationships animal lover have with their pets.

There are in fact people who have what are actually heretical views about the place of animals in God’s creation and this is revealed in their disparaging attitude towards humanity vis-a-vis the animal kingdom. Humanity is the crown of creation, not plants or animals, and it is to us that eternal life is offered. To assume that only a unloving God would deny immortality to a pet we loved is to assume that we know what the best outcome for our beloved pet would be and that if God does not agree there must be something wrong with Him. I submit to you that were you ever to discover what God’s plan was for your pet after it’s death you would be delighted with the outcome and yet ashamed that you didn’t trust God and instead tried to second-guess Him. Trust God. Be at peace. Everything will turn out better than you could have imagined. As Scripture tells us and as the above icon illustrates, the creation of the animal kingdom was the divine act of God. That He Himself called it “Good” is no small thing. Thank you very much for your time.

Thank you, Gregory. I do take your point that some icons have a didactic emphasis, whereas most only represent the person to be venerated. I personally prefer to see didactic images kept more – though not exclusively – to the medium of wall painting, mosaic or illuminated manuscripts than to panel icons.

But would you not say that it is a matter of emphasis rather than essence? One could surely still venerate Christ, Ephraim and Irenaeus in this icon, since we are ultimately venerating them as persons and not the image itself, be the icon didactic or otherwise in emphasis? The presence of the animals would not preclude this veneration, anymore than does the representation of the bound devil in the resurrection icon preclude us from venerating Christ in that icon. Or again, the horse and dragon in St George icons.

I was somewhat hesitant to accept the task of designing an icon with such an obvious – and for the icon world – new didactic emphasis, but my love of a challenge got the better of me! If I painted it again I would integrate the animals better by painting them in the same, more “abstracted”, style as the figures. What draws our attention to them at present is the naturalistic way they are rendered as well as the novelty of their inclusion.

I like your summary of the situation regarding the immortality of animals. Things that are not clearly revealed are best left up to God, and us not to speculate too much about them!

What a wonderful exchange of comments concerning this icon. If nothing else, it has prompted an examination of what an icon is or can be. The heart of the issue is a conceptual one. Let’s be honest, Mr. Hart was asked to enlist Orthodoxy in support of a social/political issue (the issue may be worthy, but, nonetheless, that’s what happened.) This already sets the whole work on shaky theological ground. The result is that Christ is present in a supporting role- conceptually. In other traditional icons presented, God is the main character. He orchestrates creation, and all the creatures around Him testify to His glory. Mr. Hart makes Christ the central figure, larger and powerful of gesture, yet, His timeless portrayal contrasts unfavorably with the very timely presented animals. The result is awkward. It is not the fault of the iconographer though. Forcing the eternal into the temporal for any agenda results in the awkward. Oddly enough, if a Latin Catholic artist presented this concept/ issue, they would have used St. Francis as a “stand-in” main character…..Mr. Hart is a great iconographer, but his task here is unenviable.

Thank you, Mr Lucas. I agree that the animals are represented in too “timely” a way, by which I am guessing you mean too naturalistic, and this to a degree draws the eye down from Christ. I think however that this is also in part due to the novelty of their inclusion. I have noticed that one of the first things people not acquainted with icons tend to ask when they see the resurrection icon is: “Who is the man bound with chains at Christ’s feet?” But we Orthodox who are used to the icon and the devil’s inclusion don’t notice him so much, and concentrate on Christ.

Regarding the theological content of the icon, I think that Dr Christine Nellist who commissioned the icon would disagree that it she was “enlisting Orthodoxy in support of a social/political issue”. As I understand it, her thesis, due to be published, is precisely an exploration of what the Church Fathers and the Scriptures say about how we should treat animals. She concluded that there is ample patristic evidence to support a theological basis for mankind not being cruel to animals.

One of the really unique things about the practice of iconography is that the artist must work within parameters. Some see this as constricting, but I believe it to be the perfect forum for creative problem solving. Your icon explores those parameters, those of both appearance and message. It is to your credit, Aidan, that you are open to the opinion of others about those parameters. You do not back away from critique and you assess your work honestly. Tradition is loyal to prototypes. Perhaps you created a prototype here. Time will judge. Thank you for responding to my comments.

With respect for my teacher, I do have one comment to add.

I question the inclusion of bible verse citations on an icon, and I suggest the inclusion of them in this icon may consciously or subconsciously be the reason some of the commentators above experienced an uneasy sense of distrust for the depiction (‘are there ulterior motives at work here’). If ever possible I would recommend all iconographers to spell out the excerpted words of any referenced text, not just give the book, chapter and verse.

In the part of the world I live in (Texas, USA) and in other similar cultural contexts, many of us are familiar with being presented with bible citations on billboards, posters, apparel, pamphlets, athletic accessories, etc. In short, we are accustomed to being shown a bible verse citation in the context of advertising – this is our reference point. And this is often a distasteful use of the holy scriptures we have experienced. The holy words of our scriptures can in these contexts be used as weapons of political or social war, as weapons of shame, fear, or coercion in a campaign to proselytize. Contemporary iconographers must take great care that didactic icons do not drift towards proselytism.

Scriptural references can have tremendous power to enrich iconographic content in very positive and profound ways, and I do not want to limit that at all. But I would recommend finding creative ways to work in all the desired words, or else leave them out, but not use citations.

I ask your prayers and forgiveness,

baker