Similar Posts

The Holy Ascension choros, which was completed Pascha 2012, has been a project eight years in the making. In 2004, my wife and I were on our way to Charleston, SC for my first job out of architecture school – to design Holy Ascension Orthodox church. On our way, we stopped in New York to visit the marvelous show at the Metropolitan Museum, “Byzantium, Faith and Power.” The treasures displayed there changed my life in many ways, but none more so than the great 13th-century choros, on loan from a museum in Munich. That choros consists of over 1100 bronze and glass parts, a delicate 12-sided ring supporting 72 candles and hung with a myriad of pendant lamps. The fixture was hung low and filled the space of the room with its crystalline forms, a crown of triumph and joy and absolute pure beauty.

That show at the Metropolitan changed the lives of many people. I remember seeing a woman, apparently secular, collapse to her knees in tears upon seeing the life-sized icons by Andrei Rublev. She and her friend were dumbfounded by the experience. I saw similar scenes of emotion and epiphany throughout that day. Never was an art show better named, for the works there embodied a power to affect faith to which modern people are unaccustomed and unguarded. For me, it was the choros that wounded my heart with joy.

When I began designing Holy Ascension Orthodox Church, I knew that it must have a choros like the one I saw. It appeared in the earliest sketches, and to my delight the congregation agreed that it must be so. Our budget was such that it fell to me to personally to make many of the decorative fittings for the church. I knew that the cost of large bronze castings was prohibitive, so I found another way to make metal chandeliers. I liked the dark patina of the Munich choros, and found I could very closely imitate its fretwork panels with steel. I draw the parts in AutoCAD and sent them to a robotic plasma cutter to cut out of a steel plate. I figured out how to make candle holders and chains and weld them on, and I developed an oxidized patina that resembles old wrought iron. Using these techniques I made several small chandeliers for the church. But the funds for the choros were not to be found at that time.

After eight years of waiting, the parish was offered a generous gift in memory of longtime parishioner George Boras, and it was agreed that this gift should go to make the choros. As I set out to draw the detailed design, I felt that I could in some ways surpass the ornamentation of the Munich choros. Typical of Byzantine metalwork, the fretwork designs in that fixture are simple, consisting only of a repeating centaur and foliage motif. I was more attracted to Medieval Russian metalwork, which was more elaborate, often incorporating paradisiacal beasts, interlace, and beautifully lettered text.

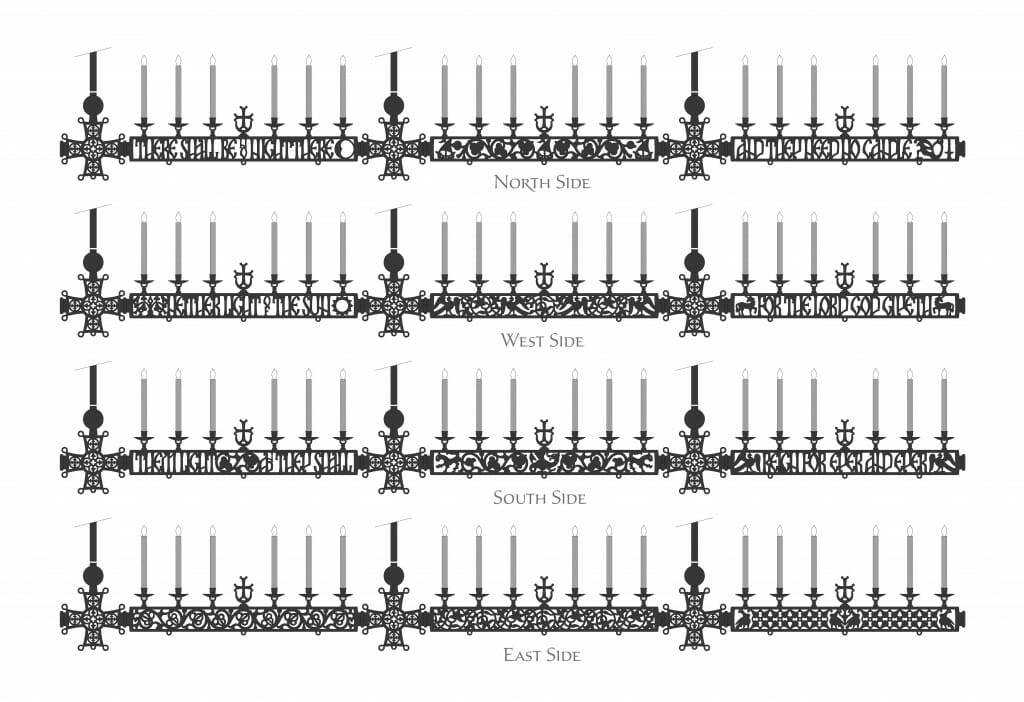

After much research, I decided that the most lively design would include a roughly equal balance of text and ornament. The text and several different patterns of foliage should alternate with a somewhat irregular and unexpected rhythm, a scintillating play of light and shadow. I had to begin by designing a new style of lettering, a stencil-like English alphabet that would capture the verticality of Old Slavonic. Then I searched my photos of Russian metalwork and found old fragments with fret-cut patterns that I could adapt for my design. An ancient rooftop cross from a 12th-century church in Vladimir served as a particular inspiration. I traced these designs in AutoCAD, careful to follow the irregularities of the originals and not kill them with the perfection of a computer drawing.

Once the pieces were cut, I welded on 168 steel hinges and 72 candle-holders. The candles are electric, fitted with beeswax-colored hand-dripped sleeves and 7.5 watt miniature bulbs. They give a light astonishingly similar to real candles. Hanging below are 48 hand-formed glass lamps, which I modeled on the ancient Byzantine-style lamps still seen in all Turkish mosques. We place vigil candles in these hanging lamps on great feasts. I installed the choros in time for Palm Sunday using a 40-foot ladder and a laser level to keep the 12 chains exactly aligned.

Originally, Byzantine churches did not have a single large fixture. They were typically lit with a many small polycandelon (polyeleos) lamps. It is known that Hagia Sophia had forty such lamps hanging from the perimeter of the dome, a corona of light encircling the nave. Beginning in the 11th-century, the lamps were connected as a single chandelier. Given the narrow vertical proportion of late-Byzantine churches, these choroi were typically small in diameter with extremely long chains. One such original choros is still in place at Decani Monastery, Kosovo. Decani is also a rare example of a church that did not subsequently install a western-style chandelier in the center of its choros, thus preserving the truly beatific vista that one can enjoy standing under the choros and looking up through it to the Pantocrator.

Interestingly, western churches were hung with somewhat similar chandeliers during the same period. The oldest surviving is the corona at Hildesheim cathedral, which dates from the mid-11th-century. It is a rigid ring with twelve miniature gate towers. The interpretation of this design is demonstrated by another German corona, that of the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, which was made in 1168. It bears a lengthy inscription around its perimeter. The text is from Revelation, and describes the New Jerusalem, a city with 12 gates, “and I saw no temple therein… for the glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light thereof.” (Rev 21:22-23) Thus, the western corona was understood as a model of the New Jerusalem – it hung from the ceiling in recollection of Saint John’s vision: “And I John saw the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband.” (Rev 21:2)

The symbolism in an Orthodox church must be somewhat different, because in Orthodoxy the entire temple represents the New Jerusalem. The meaning of the fixture in an Orthodox temple is complex, and can best be understood by examining the word ‘choros’. In ancient Greek, it was the word for a circular clearing in the forest, a meadow. In classical mythology it is the place where lovers gather secretly for trysts, where satyrs and nymphs dance to the pan flute. Churchmen boldly adopted this word to denote the circular liturgical space under the dome, a sunlit clearing in the forest of columns. Here God and man meet for their lover’s dance, and couples hold hands and walk in circles to be married, like the pagans of old. The chandelier is called choros after the circular space that it adorns. It is the wedding crown, an ornament of pure joy to celebrate the union of God and man, like the flowers and birds that ornamented the forest clearing.

The surviving Byzantine choroi do not include inscriptions, so for our choros we had to choose a text of our own. In consultation with the donor, we settled upon Revelation 21:5 “There shall be no night there; and they need no candle, neither light of the sun; for the Lord God giveth them light: and they shall reign for ever and ever.” This verse is similar to the inscription on the Aachen corona, however it does not describe the architecture of the city, but only the quality of light, and the eternal triumph of the blessed. It is a verse fitting to the role of the Orthodox choros—an instrument of illumination at the center of a temple which is itself the Heavenly City.

See more pictures of the Holy Ascension Choros on Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/andrewgould/sets/72157629868317197/