Similar Posts

Gould: You’ve only recently started making icons using chasing and repoussé, yet your first projects are nothing short of magnificent. Can you tell us something about your background, to put this work in context?

Wilson: I am a married father of two young sons, living on the outskirts of Austin, Texas. We attend Transfiguration Greek Orthodox Church.

I have been metalworking for over a decade, specializing in forged iron, bronze, and copper. For the past five years I’ve enjoyed the privilege of working as a full-time commissioned artist, designing and producing both utilitarian and artistic metalwork for churches and homes.

Prior to this chapter of life, I spent ten years in charity work – three years teaching in rural Afghanistan with a small Swedish organization, and seven in Austin leading a woodworking and blacksmithing program that offered therapeutic craft and dignified income opportunities to chronically homeless men and women.

Making art in the metal studio is a continuation of the spiritual path, rich with incarnational metaphor and opportunities for silence, contemplation, struggle, and prayer.

Gould: What made you want to start making repoussé icons?

Wilson: As a blacksmith working in solid three-dimensional material, I have typically made sculptural artwork that may not readily lend itself to liturgical use in the Eastern rite. Chasing and repoussé in semi-precious sheet metal offers an opportunity to use my tools and techniques to contribute relief iconography that remains true to the tradition.

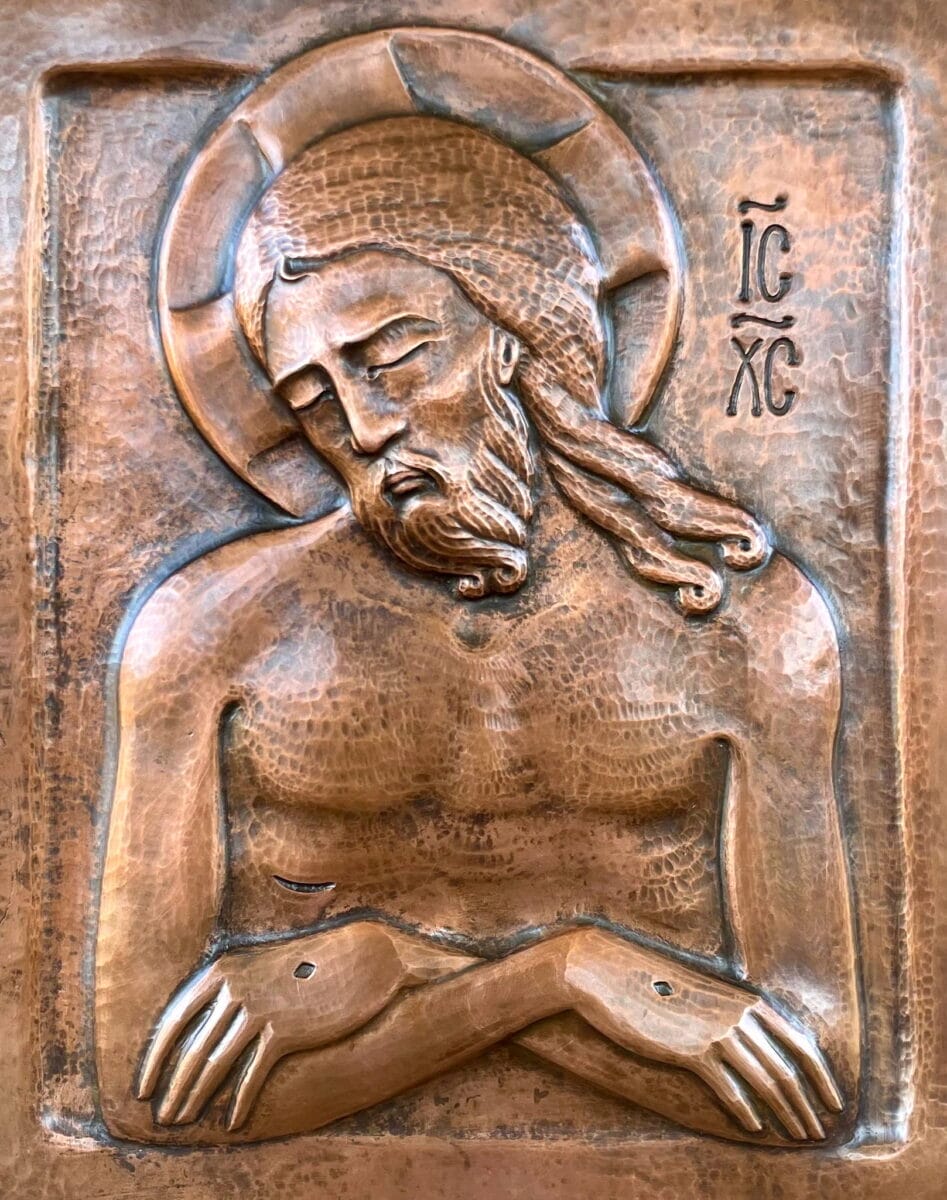

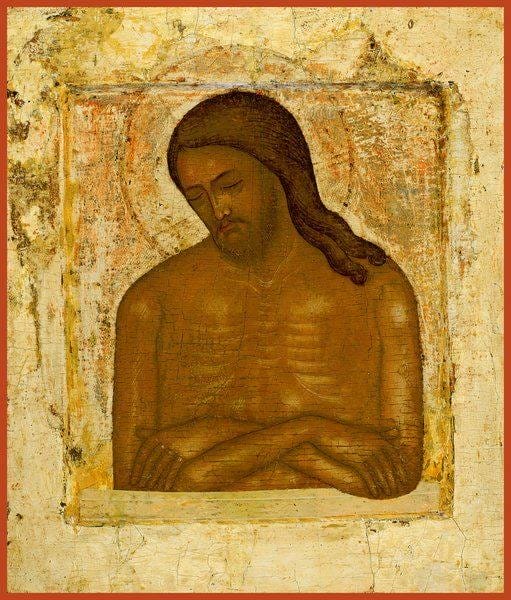

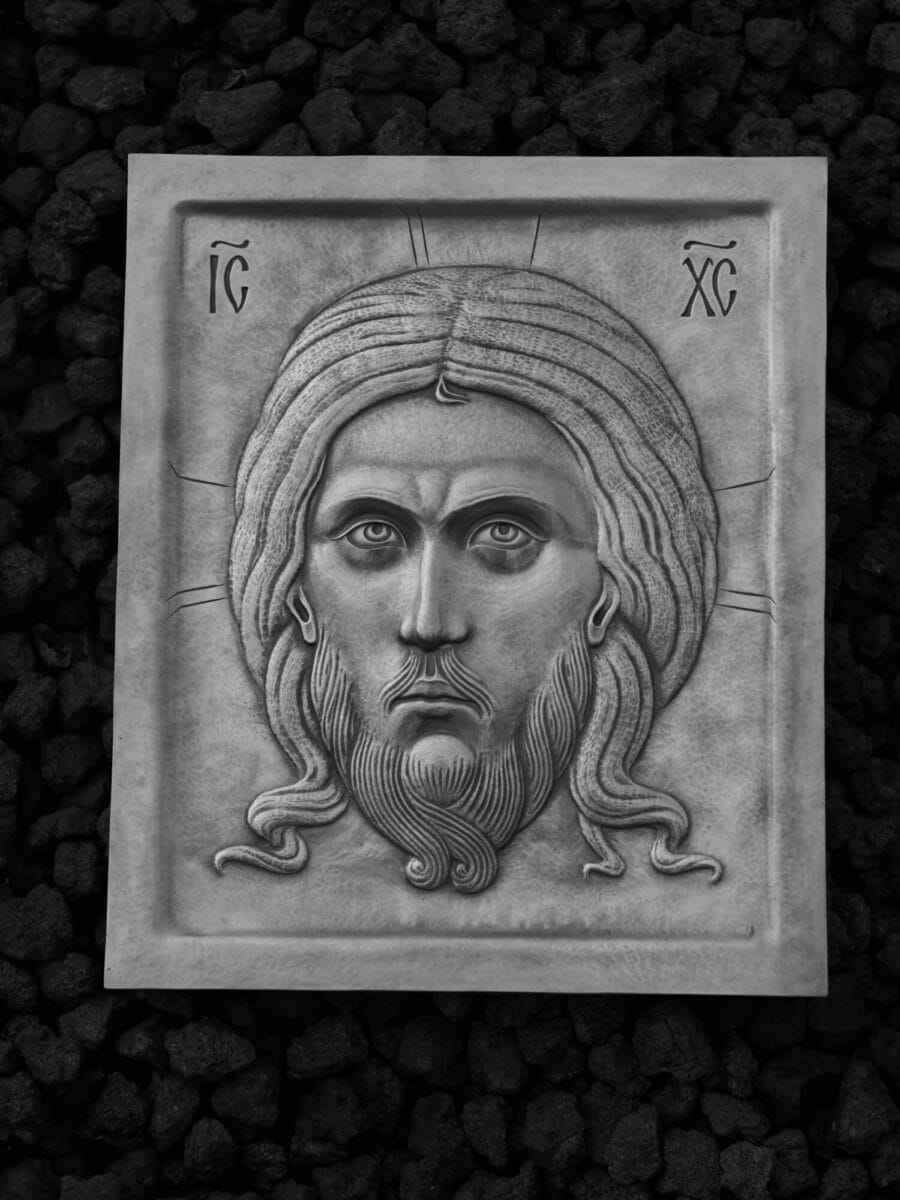

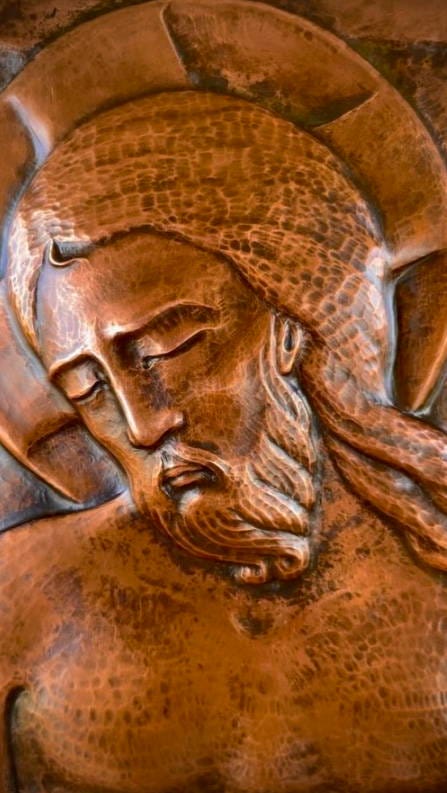

At this stage the endeavor is a speculative practice and I am curious to receive feedback on the work. Fitting time in around commissions over the past few months, I have thus far made two icons, the first being a streamlined version of the Mandylion in bronze, the second an Extreme Humility in copper.

Gould: Can you describe the process?

Wilson: From a technical standpoint, the process starts with looking through prototypes and then developing a line drawing. Once my line drawing is suitable, it is printed out in reverse and transferred to the metal using acetone.

The metal with applied drawing is pushed down into a bed of molten pitch, which is contained within the raised edges of a wooden panel. This pitch board is then mounted to a support instrument fabricated especially for this work: a hemispherical bowl of curved steel round bars topped with steel slats to which the pitch board is fastened with bolts.

The bowl, which sits on a thick wooden ring clamped to the workbench, can be freely rotated and tilted to extreme angles during the chasing and repoussé process, allowing vertical working access to oblique facets of the icon while keeping a comfortable working posture. It also allows for frequent assessment of the icon’s performance under different light-source conditions by simply repositioning the bowl under the fixed lighting of the workshop.

With the metal embedded in the pitch (which hardens as it cools to room temperature) the line drawing is “chased” into the metal using a small hammer and a dull, narrow chisel. The metal is then excavated from the pitch to be worked from the backside.

Because these metals work-harden when hammered, the piece goes through the following process: it is heated to glowing red with a torch (which softens or “anneals” the metal), and then is quenched in water, cleaned in mild acid, rinsed in water again, and air-dried. For short, I call all these steps put together a “round of annealing.”

After annealing, the pitch is melted again and the metal pushed into it – this time facedown, so that it can be worked from the back (the “repoussé” portion of the work). The chasing work in the previous step transmits a faintly raised outline of the image onto the back of the piece, serving as a guide for hammering down (that is, pushing forward) the overall volume of the form. The bulk of the repoussé is done with broad, pillow-shaped punches that move a generous amount of surface area at once, which the force of a heavier hammer helps to accomplish.

Once the repoussé work is completed, the piece goes through another round of annealing and is placed back into the pitch, with the front side up again. What follows are many hours of chasing the somewhat vague voluminous form into a precise image with appropriate relative topography in terms of its relief. A lightweight hammer and a few dozen shop-made steel chisels and punches are used to slowly develop the form, details and texture of the piece. As need for new shapes arises, new tools are made and added to the lineup.

Inevitably, multiple rounds of chasing and repoussé from front and back — each with its own round of annealing — are required to fully develop the image. Depending on the complexity of an area, some of the repoussé work can be done over a folded up sweatshirt or a clean block of wood rather than in the pitch; if it’s a simple adjustment, anything that will provide yielding support, without scratching the soft metal, can work.

Once the image is complete, lines are laid out and the sheet is trimmed to accommodate the formation of what amounts to an open-backed box. I score deep lines on the backside of the piece, such that the outer perimeter can be sharply bent back at a right angle to form a thick edge. The joints at the corners are then silver-soldered from the inside.

At that point, with the metal work done, the icon undergoes one more cleaning and rinsing cycle followed by a final finish. The Mandylion received a lightly patinated and polished treatment and is sealed with beeswax. The Extreme Humility has a darker, antiqued finish, and was sealed with lacquer and beeswax.

Gould: What surprises have you encountered?

Wilson: One surprising aspect of relief work, which seems obvious in retrospect, is how much of an effect the light source can have on the image. As the Mandylion icon neared completion, I was struck by how different the expression of Christ seems when lit from different directions.

Gould: What difficulties have you found, and how did you overcome them?

Wilson: The primary difficulty thus far was in the drawing stage – not so much the drawing itself, but ensuring that the image drawn is firmly within the tradition. For that, local Austin iconographer and OAJ contributor Baker Galloway generously gave me his time and attention along the way, offering a tremendous amount of detailed feedback, guidance, and encouragement throughout the process. I am grateful for Baker’s eye and willingness to share his knowledge and insight.

I imagine drawing will become difficult from a technical standpoint when garments come into play. These two icons offered work just far enough outside my comfort zone to allow for growth at a pace I can handle, keeping to faces, hands and the human form.

Gould: How do you see these icons being used? Is there a market for them?

Wilson: I see a wide range of potential settings for relief icons in semi-precious metal. One of the more unique applications is in exterior installations, as copper, brass and bronze endure weather for many generations without suffering any substantial change. Long-lasting outdoor icons could be of interest to parishes, monasteries, or households who wish to establish exterior places of prayer. Being lightweight, they could also be made for applying to exterior church or chapel doors.

In an outdoor context, the bright finish of a metal icon could be maintained with an occasional application of a little beeswax on a soft cloth, or it could be allowed to naturally patina in the elements, resulting in a surface like outdoor bronze statuary.

The Extreme Humility icon was recently purchased for private devotional use, presumably indoors. In that context, or in the narthex of a church, the finish would need no special maintenance and is more or less permanent — with the caveat that frequent veneration could add an extra bit of polish to certain areas over time.

Encouragingly, Aidan Hart shared with me that the metal relief icon was paramount for about three centuries after the fall of iconoclasm, which I did not previously know. Given the prominence of the painted icon today, it is unclear to me how institutions and individuals may see my work. Regardless, making these icons has been spiritually and artistically gratifying.

Gould: Absolutely. Hammer-crafted icons are very much of the iconographic tradition and have been used on metal liturgical implements in all times and places. In Georgia, they’re even more central to the tradition. In Georgia, one often sees important ‘cathedral sized’ icons completely in repoussé – both medieval and contemporary examples.

Also consider the more recent history of the metal oklad or riza, which was so often placed over a painted icon. In the 18th and 19th centuries, icons would be mounted with a repoussé riza covering everything but hands and faces. These rizas had the advantage of protecting the painted surface from damage due to kissing – a serious concern in recent centuries through to today, when kissing icons has become a ubiquitous pious practice. Painted icons simply cannot stand up to constant kissing, and painted icons on an analogion need to be behind glass.

In my opinion, your repoussé icons could serve a real need here – as the “kissing” icons presented on the icon stands in a church. They won’t need to be behind glass, and they’re easily cleaned. The tactile surface is appealing to touch (even for the blind). And if they’re made of copper or silver, the surface is anti-microbial. They would seem to be an ideal solution.

So, having completed these two icons, what do you plan to do next?

Wilson: Making “kissing” icons for churches as would be a wonderful opportunity. I welcome commissions and inquiries and hope to make more icons, whether for churches or domestic use.

The next project that involves iconography will be a collaboration with Martin Earle, to whom I was introduced a few years ago at an iconography seminar put together by Baker.

Martin graciously approached me to produce a gilded copper frontal for a stone tabernacle he has designed for a priests’ chapel at a retreat center for Catholic clergy. The doors will feature relief iconography of the Annunciation in a Romanesque style. They’ll be hung on a chased copper surround with twelve semi-precious stones in bezel settings, recalling the priestly ephod of the Old Testament.

This gilded and bejeweled project promises to take me far afield of the coal and iron of my blacksmithing background, and I am excited and honored by the challenge and opportunity to produce such a fine piece in collaboration with Martin.

Gould: I look forward to seeing that. Thank you, Evan, for sharing your beautiful work with us.

Wilson: Thank you for interviewing me, Andrew. It is an honor to have this selection of my work, small as it is, featured here on the OAJ.

Photos by Jordan Cass (black and white) and Evan Wilson (color)

Visit Evan Wilson’s website

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Congratulations, and so well done Evan. You give us just enough insight into your craft to educate and impress, but also to let us know that we can’t do what you do. Ha!

Thanks to you too Andrew for the feature and great questions.

Beautiful and sensible. I love how you capture the icon in a way that is both traditional and surprising.

The icons are so beautiful. Thank you for outlining the process, so interesting!

Gorgeous work! I can’t wait to see What more you make in the future! Glory to God!

Thanks Evan and thanks Andrew.

You both make the most beautiful things.

Evan just showed us his inspired crafmanship.

And I remember Andrew from joining his splendid Orthodox Balkan trip 2 years ago.

Peter NL

Great article, and beautiful work. I am eager to see you lean in to some Romanesque forms!

Wonderful chased work! The Mandylion especially is outstanding. You have certainly inspired me. Thank you Evan and Andrew.

Thoroughly beautiful and refreshing. The Mandylion in particular is breathtaking. What I find striking is the fluidity of form you are able to create in this piece of metalwork. You have gone beyond the self conscious iconographic representations of the Mandylion. When the iconographer ( thanks be to God) is able to create an image which draws one into prayer by communicating the form in such a way that the pray-er forgets the medium but sees the Face or faces of the holy ones represented, it is wonderful. Thank you for sharing your work.