Similar Posts

Leonid Ouspensky, from his apartment/studio in Paris taught many young artists and created some of the finest iconography and iconographers of the 20th century. Recently, one of his pupils, Joris (George) Van Ael, came to my attention. Van Ael’s style is strongly reminiscent of others of the Ouspensky school like Fr. Patrick Doolan and Matushka Anne Margitich. These and other disciples of Ouspenky are among the very best iconographers of our times. What makes Van Ael stand out among this group is his application of his talents and training in a unique way.

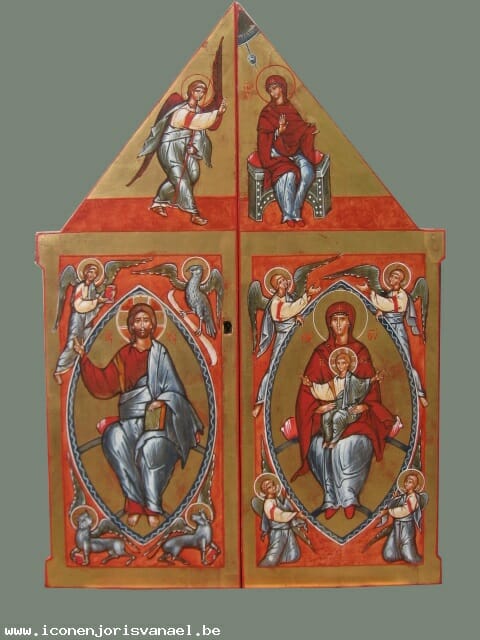

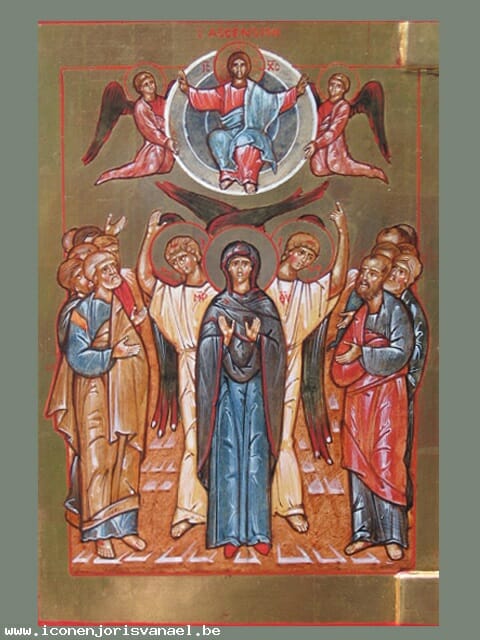

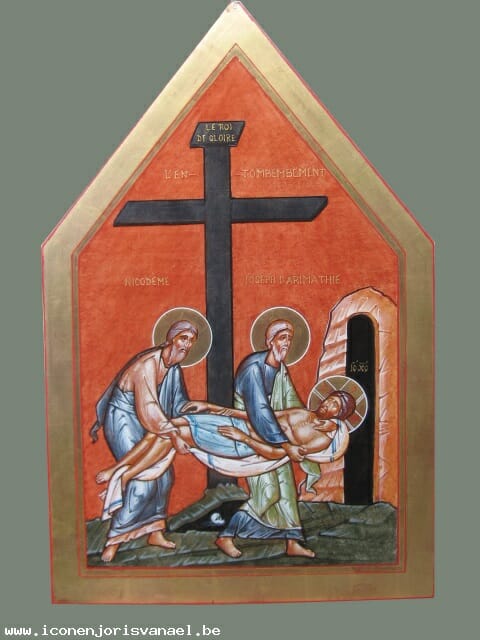

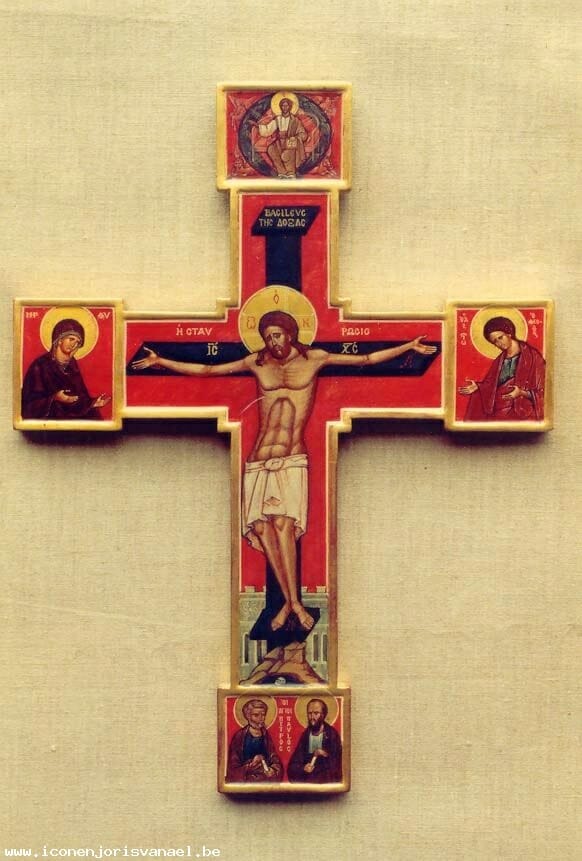

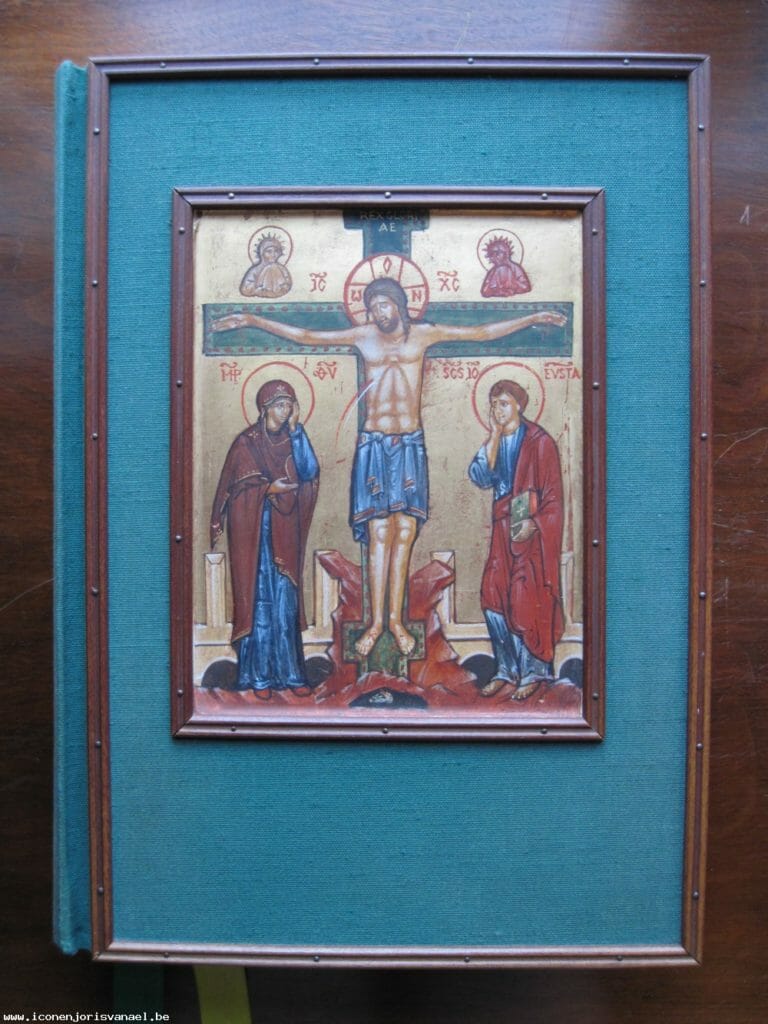

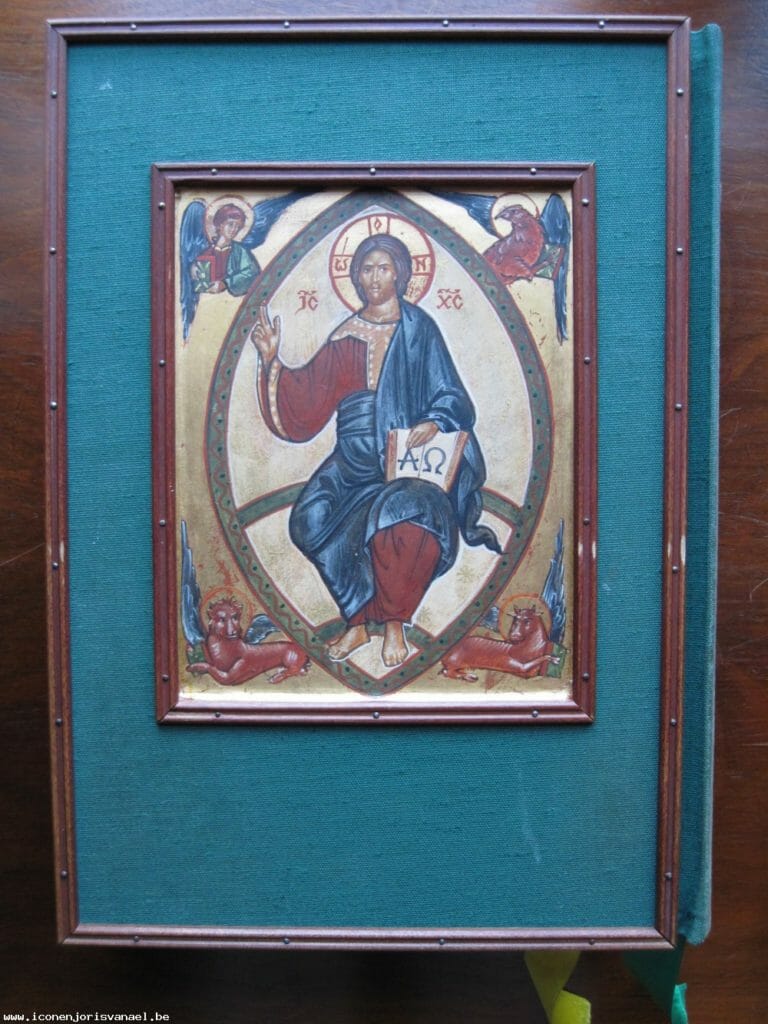

Most interesting among Van Ael’s portfolio are his liturgical implements – tabernacles, altar crosses, and Gospel Covers – designed for Roman Catholic use. These are beautiful additions to the liturgical life of the monasteries and parishes in which they now reside. Moreover, by form and function, they hearken back to medieval Europe’s finest Romanesque and Gothic liturgical art. But with their “Russian” iconographic depictions, these are a deviation away from western precedents, a twist on an old theme and the start of something new.

The outside of the tabernacle doors: The Annunciation – Top, Christ Pantokrator and Evangelists – left. Mary the Seat of Wisdom – right.

This work has a beautiful stylistic blend. The tabernacle is exceptional.

My opinion is that Joris Van Ael ought move away from the Russian style for Roman Catholics and instead use a more pure Italian form of iconography from duecento and earlier – before giotto, circa 500 AD – 1270 AD.

There is no doubt in my mind that Italy is the ideal model that is universally appealing to Roman Catholics and is distinctinctly different from that 16th c. post-byzantine and russian styles of the last 500 years, even while retaining a basic harmony and shared vocabulary with them.

For examples of a more “pure romanesque/italo-byzantine/late antique” form:

Church of (Chiesa di) San Pietro al Monte, Civate, Italia (10-11th c.)

Chapel of SS. Eldradus and Nicholas, abbey of Novalesa, Italy (11th c)

Church of Sant Quirz de Pedret, Catalunya, Espana (12th c.)

Chapel of St. Sylvester, Quattro Santi Coronati, Roma, Italia

Manuscript – Hortus Deliciarum, (late 12th c.), Herrad of Hohenburg

The Codex Benedictus, various Monte Cassino MS. Exultet rolls, and surviving frescos .

Visit all the medieval art museums in Italy to get an idea and stay away from post 13th c. work, after than humanist creativity took it’s toll.

The Oratory of S. Gregory Nazianzen – late 12th c. – Vatican 2009

Coppo di Marcovaldo’s works, such as the image of S. Francis – wth two angels and 20 scenes of his life.

While the work is quite lovely, and a vast improvement over much of the iconoclasm and modernism pervading the post-vatican II era – it would not have been permitted to be done precisely in that manner before the 1950’s. Certain elements are out of place. The Latin tradition is very distinctive, it must worked within the tradition rather than outside it. The earlier pre-14th c. byzantine style is more harmonious with the latin church tradition. Ecumenism has it’s limits. I hope you don’t think my views too harsh.

Although I can understand the comment made and appreciate the logic behind it, I think there is a necessary buffer which will appear as Catholic artists rediscover a fuller Western tradition. Because traditional Western art has been so affected by historical developments since the Renaissance, many Catholic iconographers are learning from Russians in a manner that is a truly living transmission of tradition rather than what we could call a historical/archeological approach. It is not just to copy a style that was done 600 years ago, but to learn a sacred language. Therefore I think in time a truly integrated Western art can appear, but to rush things artificially would harbor the danger of pastiche. Even in the work presented here, although we sense the Ouspensky/Krug influence, one can also see the mandorlas with color and motifs in them, the Holy Virgin in a mandorla, a “lamb of God”, all of these are Western motifs. I think it is a slow, healthy approach.