Similar Posts

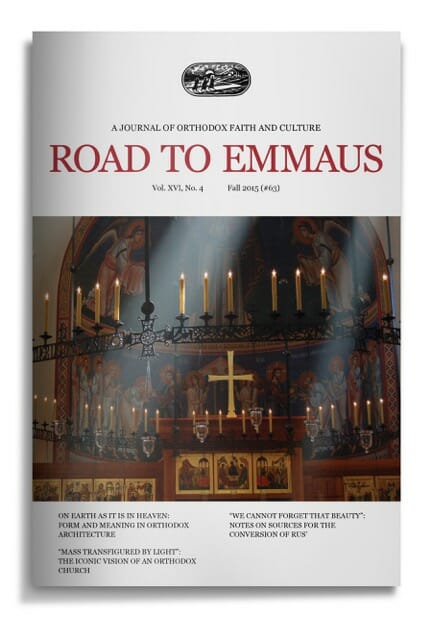

I have had the great honor of being interviewed for the Road to Emmaus Journal. In June of this year, I spent a week with editor Mother Nectaria (McLees), discussing the art and architecture of the Orthodox Church. It was a marvelous and fruitful experience, and I am truly humbled that my words were found worthy for such an estimable publication

Our discussion will be featured in two consecutive issues. The first issue, being mailed out to subscribers this week, can be ordered here.

The issue begins with the republication of an essay I wrote in 2007, On Earth as it is in Heaven: Form and Meaning in Orthodox Architecture. This essay offers historical and theological interpretations of the architectural patterns of traditional Orthodox temples. It is probably the first such essay in the English language.

The issue proceeds to the first half of our discussion, titled “Mass Transfigured by Light”: The Iconic Vision of an Orthodox Church. Here I revisit the ideas in my essay, building upon them in much greater detail. In particular, we speak at length about the importance of the iconostasis, the modern history of medieval-revival architecture, a practical Orthodox understanding of beauty, and what we can learn from regional variation in liturgical art.

The following are some brief excerpts from the current issue.

On the emissaries of St. Vladimir:

In Islam they build mosques that have the quality of jewel boxes. They are ornamented with a tremendous richness and regal splendor, but are completely devoid of anything iconographic, anything representational. They seem like abstract spaces, as does the Muslim worship within these spaces — the bowing down toward a mihrab, which is, in and of itself, nothing, but only an abstract architectural gesture that indicates the direction of Mecca. And of course, the Islamic faith emphasizes that man is very low and that God is very high, and that, really, the two do not meet; they surely do not meet in the sense that they meet in Christianity. So regardless of how beautiful a mosque may be, mosque architecture has never sought to convey an impression that God is within the mosque. It only conveys the impression that man has attempted to dignify himself by beautifying the mosque to an extent that man might be found worthy to kneel before God (because, of course, one only kneels in a mosque). So, if it is true that the emissaries of St. Vladimir attended services in an Orthodox Church, a Catholic Church, and in a mosque, I think it’s very appropriate that they would have observed that only in the Orthodox Church does it seem that God dwells with men. The very specific and deliberate attempt of Orthodox liturgical art is to convey that impression, and this is, of course, the fundamental gospel of Christianity.

On the iconostasis:

The question of whether an iconostasis should be transparent or opaque is almost the same as asking whether the altar should be holy or not, because holiness, sanctity, simply means being set apart. Because we are Christians and not pagans, we do not believe that holy things have intrinsic holiness due to magical qualities, that is to say, we don’t make an idol out of the altar and believe that God actually lives in there, the way primitive pagans might. We know that the altar is simply a table like any other, and therefore the only thing that makes it holy is that we set it apart for holy use. In an architectural sense the way we set it apart is by putting it behind a wall. The wall doesn’t only set the altar outside of our space, but also outside of ordinary life by dignifying it with a gilded and divine beauty. The iconostasis looks like the very gate of heaven. The altar appears holy to us in proportion to the intensity of these architectural gestures…

This modern war on iconostases, where people pass judgment on these screens as some kind of pastoral or pedagogical hindrance to observing what is going on up at the altar, is a tragedy and an embarrassment. We should really step back and consider this exchange we are making. We are saying that the act of observing the priest and the altar boys shuffling around behind the iconostasis and moving the vessels on and off the table and doing what little physical role they have there – that the mere act of observing this, and the marginal amount of pedagogical or pastoral value that may have — is more important than the vision of divine splendor in the fully-developed iconostasis, which gives us a glimpse of the very energy and divine fire that surrounds the throne of God. It’s a great shame upon modern people that they would look upon that as some kind of fair trade.

On the quality of light:

A good modern building flooded with white light can be beautiful and people will often call such a building uplifting or inspiring. But we need to remember that the purpose of liturgical architecture, of an Orthodox church, is not to uplift and inspire but to make us mindful of the presence of God and the saints. Traditional architecture does this iconographically by revealing the beauty of the uncreated light shining through the saints, through the icons, and by suggesting the veil of mystery and the cloud of witnesses around the altar. For this iconographic technology to be effective requires a certain dim and mysterious light so that the reflections of light off of the gilded icons can be seen as brilliant and even supernatural in the setting of a dark church. A church that is flooded with natural light robs the icons of their ability to shine more brightly than the sun.

The complete issue can be ordered here. If you do not already receive the Road to Emmaus Journal, I highly recommend a subscription. I have personally found RTE to be among the most inspiring expressions of Orthodoxy I have ever encountered.

Andrew Gould

Dear Andrew,

I look forward to reading your article. However, as the priest of a Western Rite parish, I would note that you shouldn’t overlook the thousand years of Western Orthodox church architecture, which developed differently from the East. In fact, St. Vladimir’s emissaries didn’t visit an Orthodox church and a Catholic church; they visited two Orthodox churches, one Eastern and one Western.

Fr. David Kinghorn

St. Cuthbert’s Orthodox Church, Pawtucket, RI

Hi Fr. David,

You’ll be pleased to see that I talk about Western medieval architecture quite a bit in this issue – especially with regards to the 19th century revival of medieval church architecture. In the next issue of RTE, we have a discussion of stained glass in Western architecture.

Of course, you’re correct that in the 10th century the Church was united, but I think that even at that time one would have perceived a difference in liturgical ethos and emphasis – a growing ecclesiastical extroversion in the West, and a preference for liturgical introversion in the East. These differences manifest themselves clearly centuries later when we see the West building the great Gothic cathedrals and at the same time the East building the tiny mosaic-encrusted churches of the late-Byzantine period. I place no value judgement on these differences. (No one loves western medieval architecture more than I do.) But I think the Russian emissaries could have perceived a spiritual and cultural difference there, and understood that the introspective liturgy of the East was a better fit for the Russian people.

The Primary Chronicle records they visited a German (“Western”) church (?) and those of “the Greeks”:

Reminds me of this from Iconostasis:

“[T]his material iconostasis does not conceal from the believer (as someone in ignorant self-absorption might imagine) some sharp mystery; on the contrary, the iconostasis points out to the half-blind the Mysteries of the altar, opens for them an entrance into a world closed to them by their own stuckness, cries into their deaf ears the voice of the Heavenly Kingdom …” —Pavel Florensky