Similar Posts

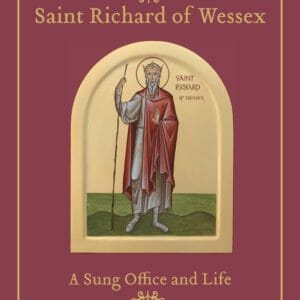

Panel icon of St. Richard of Wessex by Brian Whirledge.

Overview: On the evening of 6 February 2022, Dormition of the Virgin Mary Greek Orthodox Church in Somerville, Massachusetts celebrated an All-Night Vigil (full festal Vespers, Orthros, and Divine Liturgy served consecutively) for Saint Richard of Wessex (7 February, +722 A.D.). At the altar were three priests:

- Rev. Fr. Anthony Tandilyan, proistamenos of Dormition

- Rev. Fr. Dr. Romanos Karanos, Professor of Byzantine Music at Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology

- Rev. Fr. Dr. Costin Popescu, proistamenos of Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church in Newburyport, MA and Spiritual Advisor for the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Boston Choir Federation

Antiphonal Byzantine choirs comprising cantors and singers from around the country sang the service. While not everybody was able to stay for the entire Vigil, both left and right choirs had as many as 11 people each throughout the evening. The choirs included:

- John Michael Boyer and Photini Downie Robinson, protopsaltis and lampadarios respectively of Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Portland, Oregon

- Constantine Kokenes of St. Philothea Greek Orthodox Church in Athens, Georgia

- Brian Matthew Whirledge of St. Mary’s Antiochian Orthodox Church in Goshen, Indiana

- Charlie Marge and Teri Stevens Marge of St. Mary’s Antiochian Orthodox Church in Cambridge, MA

- Dina Marinakos of St. Nektarios Greek Orthodox Church in Charlotte, North Carolina

- Dn. Michael Abrahamson of St. Michael Ukrainian Orthodox Church in Woonsocket, Rhode Island

- Kamal Hourani of Sharon, MA, and others.

At the Lity, the clergy processed with a new panel icon of St. Richard, painted by Brian Whirledge in egg tempera and gold leaf. In attendance were Dormition parishioners and other visitors.

The office for Saint Richard employed in the Vigil was a new English-language composition that I wrote over the last three and a half years. In addition, I composed the doxastikon for the saint at Lord, I have cried. An array of some of the best living chant composers for English set the doxastika for the Aposticha and Lauds, as well as the Lity idiomela and the post-Psalm 50 idiomelon at Orthros, including:

- John Michael Boyer

- Gabriel Cremeens

- Fr. Seraphim Dedes

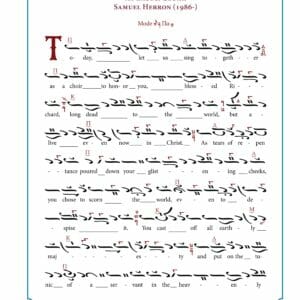

- Samuel Herron

- Chadi Karam

- Phillip Carl Phares

- Nicholas Roumas

- Jessica Suchy-Pilalis

The service order we followed may be found here, and the parish’s archived video of the livestream may be viewed here:

How and why did three clergy of the the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese, originally from Armenia, Greece, and Romania, as well as several experienced and capable cantors and singers from multiple jurisdictions around the country, come to a GOA parish that is home to fourth-generation Greek-Americans in the Boston metro area, to celebrate an All-Night Vigil for an obscure eighth-century English saint who never had an office in the Byzantine rite until a 21st century American layperson wrote one?

This is a story with multiple dimensions – personal, spiritual, musical, artistic, liturgical, historical, cultural, philological, ethnomusicological, and sociological, at least. For present purposes I will focus primarily on the personal, musical, artistic, and liturgical aspects, but I will at least nod in the directions of the others as appropriate.

Background and composition: In February 2005, by the grace of God, I was received into the Orthodox Church. During the two year course of my instruction in the faith, the question of a “proper saint’s name” arose. Many of the converts I had met who were not already named some form of Paul or John or Mary had taken names such as Photios, Nektarios, Maximos, and so on. These are all great saints, of course, and it would be a great privilege to have the prayers of any one of them as my patron. At the same time, I was, and remain, of the conviction that names are more properly given than taken, and I have always intentionally introduced myself as “Richard” rather than any of the name’s derivatives (save for a brief period in elementary school when I was “Rich”).

Additionally, I also believed, and believe, that being an Orthodox Christian of Anglo-European heritage in a context of 21st century North America was already a sufficient exercise in self-consciousness without adding the extra layer of a name that was very obviously not what my parents named me. Previously I had been aware of the thirteenth-century Saint Richard of Chichester, but as he seemed to be rather too late of an English saint for Orthodox consideration, he could not be the basis for any claim that I already had a “proper saint’s name.”

Then I found an icon for Saint Richard, King of Wessex, celebrated on 7 February, previously unknown to me. He reposed in 722 AD, certainly early enough for Orthodox purposes, even if the tradition around him did not exactly appear to be robust. On the back of the icon was the text for a “troparion” of unclear provenance, but it was clear enough otherwise that there was no real liturgical practice of commemorating him in the East. It was a starting point nonetheless, and I was received with Saint Richard as my patron.

Over the years, I collected such data as I could find about the saint, which truthfully were not exactly plentiful. The basic narrative was that he was an English pilgrim traveling to Rome and the Holy Land with his sons; he fell ill and reposed in Lucca, Italy, where he was buried at the church of Saint Frigdian (San Frediano); his relics were reported to be miraculous, and thus a tradition of veneration arose. More details seemed to be reported about his remarkably holy family than him; his children were all saints (Saints Willibald, Winnebald, and Walpurga), his wife was a saint (Saint Wuna), and his brother was the much-renowned Saint Boniface, the Apostle to the Germans.

Curiously, some reports emphasized that certain sources did not even name him or call him a king; of course, I had known since I was child that “Richard” meant, roughly, “powerful ruler” or “king,” so “Richard the King” was, in a way, functioning as an emphatic rather than a name. In any event, “Richard” is semantically equivalent to the Greek Βασίλειος, Saint Basil (and in certain Greek ecclesiastical contexts I refer to myself as Βασίλειος or Βασίλης simply for expediency).

Eventually, I started pondering how I might advocate my patron’s liturgical commemoration. The aforementioned troparion on the icon was clearly an insufficient argument for any kind of service, and while Vladimir Moss has done groundbreaking work with his service for All Saints of the British Isles, even that makes no mention of Saint Richard. Similarly, the following reference to him in the 7 February Synaxarion is the entirety of his recognition in Holy Transfiguration Monastery’s Menaion:

+ On this day we commemorate the holy Sovereign Richard of Wessex.

Man’s wit wotteth not what awaiteth King Richard,

Richer than a king in the love of Christ Jesus.

Again, this is hardly adequate. I considered the project of writing a rather self-consciously archaic full-length kontakion, but I couldn’t overcome my own internal objection that there was no living tradition for the form that could support such an effort, not without turning to the later Slavic development of the “akathist” genre, which did not seem to be quite what I was after.

If my objective was to forge a path to popular liturgical commemoration of my patron saint, then it seemed to me that a service was needed that would be intelligible to English speakers and compatible with existing musical repertories. In other words, if I wanted Greek and Russian churches to celebrate Saint Richard of Wessex, there needed to be a text that they could use to do so in a way they understood. Αt the same time, if I wanted English speakers to celebrate Saint Richard of Wessex, then the hymnography needed to be composed in English for English speakers. It needed to be singable by everybody, while still being comprehensible in the source language. To offer a counterexample – the OCA’s service for All Saints of North America, while easily usable in Slavic liturgical environments, is challenging at best to employ in a Byzantine chant context, and would require extensive metering work to achieve the kind of mutual intelligibility I mean.

I eventually decided on a complete office — a full Vespers and Orthros, along with the necessary variables for Divine Liturgy — with prosomoia and a canon written to be sung to the model melodies of Byzantine chant, with through-composed idiomela for the Doxastika, Lity, and so on. This was to be a different beast altogether than metrical translation; these would be new English hymns composed for those melodies from scratch. The text would be poetic while still striving to have reasonably straightforward syntax, so that it could be sung in the various Slavic chant systems that do not require such strict metrical consideration without sounding too self-conscious. With these matters in mind, and with an eye towards the semantic equivalence between Richard and Basil, I sketched out an apolytikion using the standard Greek version of Saint Basil’s apolytikion, Εἰς πάσαν τὴν γὴν, as the model melody.

Apolytikion. Mode I. Εἰς πᾶσαν τὴν γὴν ἐξῆλθεν ὁ φθόγγος σου.

Renouncing your reign, you left for Jerusalem, * in saintly fellowship with your kin. * In Lucca you departed your earthly life; * your children thus laid you to blessed rest. * You proved your regal spirit by your miracles, fulfilling the promise of your name. * Holy Father Richard, king who in death revealed our God, * beseech our Savior Christ that he will save our souls.

Quickly, however, I ran into two problems — or rather, a new problem arose while an old problem continued to be a nuisance. The new problem was that offices generally follow precedents according to the type of saint commemorated. There are martyr saints, ascetic saints, confessor saints, and so on, and these categories generally guide the selections of readings, automela, heirmoi for canons, and so on. Saint Basil was not entirely helpful in this regard, since he is a different class of saint and much of the hymnography for 1 January is for the Feast of the Circumcision of Our Lord. There are also not many king saints in Byzantine liturgical practice; Ss. Constantine and Helen, for example, are commemorated as Equals-to-the-Apostles, not as royalty. The Russians have many, but those services are largely composed with different considerations in mind than what I was aiming for. Eventually I found a useful Greek precedent, Saint John Vatatzes the Merciful King, who had not one but two extant offices.

The second issue was more vexing: there was still a paucity of any kind of tradition surrounding Saint Richard that could serve as source material for all of the hymnography. I drafted a small handful of prosomoia with what I had, but it was going to be a tremendous challenge to fill out Vespers and Orthros.

Thanks to my godson Fr. Lucas Christensen, I was able to access an article that traced the development of Saint Richard’s veneration and collected a great deal of his Latin hagiography, including an antiphon (Coens, ‘Légende et miracles du Roi S. Richard’, Analecta Bollandiana, 49 (1931), pp. 353–97). This was a treasure trove, and without it, there would have been no way for me to write any version of the office that did not devolve irretrievably into solipsism (arguably already a danger for somebody presuming to take it upon himself to write a festal office for his own patron saint). By the grace of God and with Saint Richard’s prayers, I finished a draft of the hymnography in November 2021, and after harmonizing and abbreviating the Latin versions of the life, I had a complete working draft of the office for purposes of an All-Night Vigil on 3 January 2022.

Themes: It has to be acknowledged that Saint Richard is not a saint of great theological output or complexity, unlike Saint Basil; the hagiography consists of a straightforward, if interrupted, pilgrimage story, beginning with the king renouncing all worldly possessions and trappings after the fashion of Saint Anthony, accompanying his sons on pilgrimage to the holy places of Rome and Jerusalem, and then dying in Lucca, where miracles occurred at his tomb.

Nonetheless, the fuller accounts collected by Fr. Coens contain wonderful themes for the Christian to take from Saint Richard’s life. In the lives, we read about a man of worldly authority, rank, and privilege, and at least nominally observant as a Christian – enough to raise his children in the faith – whose own children convict him of not doing enough. The trappings of wealth and power are, rather, a trap for Richard’s soul, and he must escape so that he may love Christ fully with his whole heart and set the proper example for his family.

The upside-down nature of the Kingdom of Heaven is also a running theme. The hagiographers paint an image of Richard receiving his children’s loving rebuke with tears of humble repentance streaming down his face, moving him to cast off his throne, crown, sceptre, and robes, putting on rather a pauper’s cloak and picking up a wanderer’s staff. The world’s images of status are reversed, and no longer a king with his own realm, he sets out to see the holy places far from his own island. Richard’s death is also itself a reversal; in dying before he reaches Rome and Jerusalem, surely there is an echo of Moses not reaching the Promised Land (and I acknowledge that in one of the kathisma prosomoia). Even more significantly, however, while he does not reach the earthly shrines, the pilgrimage brings him rather to the heavenly kingdom, where he is now a servant among servants, and an instrument for God’s miracles here on earth. Richard’s upside-down journey from worldly king to a saint is complete.

While not centering on arguments about the nature of the Trinity or visions of the third heaven or graphic martyrdoms, surely Saint Richard’s example is one all we Christians, regardless of heritage, would benefit from hearing regularly and having it reinforced through incorporation into the normal liturgical cycle.

Context: To speak briefly about the wider cultural context of this service’s composition – as I suggest above about the experience of converting, there is an irreducible and unavoidable amount of self-conscious anachronism, as well as anatopism, and perhaps even presumption, involved in the exercise of an Anglo-Danish American writing a Vigil office for the present-day Byzantine rite using early medieval Greek poetic forms in modern English for the eighth century English saint who is the would-be hymnographer’s patron.

One might even suggest in this day and age that there is no minor whiff of cultural appropriation here. This is a fair concern, to be sure. I am a white American Anglophone man with no ties of heritage to any Orthodox Church, only those of choice in America’s religious “free market,” taking it upon myself to invent a devotion within a specific form with a particular cultural history for a saint who also does not come from that culture. I am also doing so in a language which has an asymmetrical power relationship to the historic language of the form, and to the extent that English has a history with this form at all, it is recent at best, and only then in the context of translation, not creation.

There might also be parallel concerns going the other direction. Why does worship of a Western, specifically English, saint need to conform to Eastern, specifically Greek, norms? Even if the service is conceived of and composed in English, is this not a square peg/round hole kind of exercise, forcing the expression of devotion into non-native forms, effectively doing little more than dressing up Saint Richard in culturally inappropriate Byzantine drag? Is this not in some way denying that Anglophone Orthodoxy can and should have its own native expression, one that must be conceived of as going beyond jamming English syllables into melodies conceived for Greek meter and syntax? Is this not a form of liturgical colonialism?

These are all important, ongoing issues to which there are no easy resolutions for anybody. What I will offer is this: fundamentally, Orthodox Christianity sees itself as universal, not exclusive to people of a particular set of ethnicities only. It may be culturally specific, but it is by no means culturally exclusive. As a core musical repertory, Byzantine chant is also not limited to Greek; it is a form of sacred musical expression that speakers of Arabic, Russian, Romanian, Armenian, Finnish, Estonian, Georgian, Albanian, Turkish, French, German, Italian, and Spanish (and more!) have adopted for worship in their Orthodox churches. From the ecclesiastical perspective of the Byzantine rite and its music as a form of worship for a Church with an evangelistic mission, composing an office for a local saint in the local language and doing so according to the norms of the church venerating that saint should be a mostly-unremarkable activity. This is the heavenly reality, let us say; the ideal that we strive for.

At the same time, to leave it there would be too facile, and would also be to disregard earthly realities of power asymmetries between cultures, particularly in diasporic contexts such North America. (I am aware that “diaspora” is a word some find distasteful when discussing Orthodoxy in North America; would that it were a simple matter to dismiss it altogether. I use it here to acknowledge a technical reality as well as the lived experience for many Orthodox Christians here.)

We must acknowledge multiple things as being true: Orthodox Christianity properly has an evangelistic mindset, and the Orthodox Churches that exist in Anglophone contexts have complex histories stemming from immigration, acculturation, religious renewal movements, and so on. In this context, English language worship – let alone liturgical creation in English – within some Orthodox communities is hotly contested, and there are substantial reasons for why it is contested. I have experienced the implications of this firsthand on an individual level, the parish level, and the higher administrative levels of diocese and archdiocese. While there is a heavenly reality to which we aspire, there are obstacles here on the ground that we must acknowledge and grapple with.

To that end, while this is not the appropriate place for my curriculum vitae, I will nonetheless offer the following: I am a practicing Orthodox Christian and an active cantor, and I have spent several years within various linguistic, musical, liturgical, geographic, and cultural contexts of Orthodox Christianity. I took on the effort of writing Saint Richard’s office with seriousness, and only after much formation within those contexts.

As for concerns about Byzantine liturgical colonialism, all I can offer is that my normative liturgical experience as an Anglo-Danish American Orthodox Christian is within the context of the Byzantine rite, with Byzantine chant as the predominant musical idiom, sung in both Greek and English. Given the wider linguistic context of Byzantine chant and hymnographic forms outside of Greek, I fully embrace the idea that model melodies and musical patterns of Byzantine music can be applied appropriately to English. To lay my cards fully on the table, I take it as a given that this is so, and that this should be considered normative (even if its fullest expression will require an iterative process over time). As far as the Byzantine rite itself, I will note that Orthodoxy’s adoption of the various forms of the Western rite has not been universal by any means, and in any event I do not have anywhere near a sufficient level of experience with any form of the Western rite to be able to create a service for it.

Is that sufficient to quell such concerns as may be had? It is ultimately not for me to say. In 2019, UNESCO added Byzantine chant to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity; as part of their definition of “intangible cultural heritage,” UNESCO includes the characteristic of “community-based” – that is, “intangible cultural heritage can only be heritage when it is recognized as such by the communities, groups or individuals that create, maintain and transmit it – without their recognition, nobody else can decide for them that a given expression or practice is their heritage.” Whether or not this effort will be embraced by the Orthodox community at large is for that self same community to decide, not an individual; it would be silly on its face for me to lay claim to any control over that.

Regarding the text: I had several objectives in writing the text. First and foremost, I set out to write an English-language office that would follow the conventions of a festal akolouthia that were common to Greek offices, so that the service would be mutually intelligible for both English speakers as well as Greek cantors, with neither language nor hymnographic form serving as a barrier. The intent was to show that it could be done, that the metrical conventions for Byzantine prosomoia and heirmoi do not have to be antagonistic to reasonably straightforward – if elevated – English, that English texts composed in this context do not necessarily result from a series of more or less bad compromise choices, and that good Byzantine chant can be composed using such texts as the basis.

Generally speaking, I have employed a modern register of English. This is the express preference of the jurisdiction to which I belong (Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America), and it is my native dialect. It would not be possible for me to compose in the neo-Jacobean approach to English that some euphemistically refer to as “hieratic” (and which Archimandrite Ephrem (Lash) of blessed memory once called “hyper-Cranmerian”), at least not without it being a clumsy affect at best coming from my pen. That said, “modern” need not equate to “street level.” I believe there are sufficient models in 2022 of what reverent modern English can look like, and in no way do I consider this a deficiency option.

Nor does “modern” need to mean “flat.” Upon first meeting me and hearing one of my frequent, room-clearing puns, Fr. Seraphim Dedes (now the chief liturgical translator of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America) asked me, “Can you put that skill to use for good and become a hymnographer?” The great Byzantine hymnographers all used wordplay extensively, and with Fr. Seraphim’s encouragement in mind, puns, alliteration, “quaint” word choices, and so on are all tools I have felt free to keep at the ready. Other devices common to Byzantine hymnography are paradox and contrast, and I found I could easily apply them to the themes of reversal in Saint Richard’s life that I discuss above.

The canon, which has the acrostic “RICHARD THE SINGER’S HYMN FOR ST. RICHARD,” employs many such devices. Consider this troparion in the ninth ode:

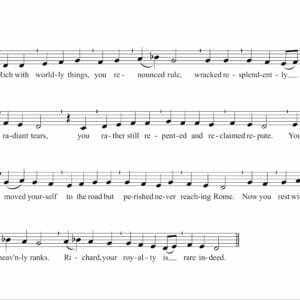

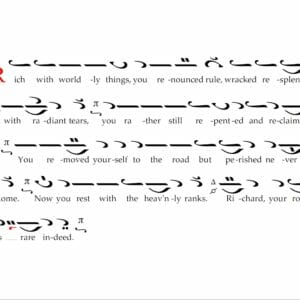

Rich with worldly things, you renounced rule; * wracked resplendently with radiant tears, * you rather still repented and reclaimed repute. * You removed yourself to the road * but perished never reaching Rome. * Now you rest with the heavenly ranks. * Richard, your royalty is rare indeed.

- Ode 9, Troparion 4, staff notation

- Ode 9, Troparion 4, Byzantine notation

Alliteration on the “R” sound is a device I use throughout the office, especially in the canon troparia that begin with it. As a quick, short, syllabic troparion, this isn’t really the place to develop a big idea but rather to recap, and that quickly, so alliteration allows for some distinction and variety even with narrative content that is by this point in the service familiar.

Another example is the fourth idiomelon of the Lity:

O blessed children, Saints Winnebald, Willibald, and Walpurga, you saw that riches and royalty risked the ruin of your father Richard’s soul among the wrecks of unrepentant rulers. You loved your father dearly, and spoke the truth to him with perfect purity: “Sweetest father, you dedicated us to Christ, but you devote yourself to the world all too eagerly. You are dividing your own house faithlessly, dearest father; and yet, Noah, with faith in God’s command, built the ark and embarked with his sons, and our Lord went before his apostles to the Passion. Trust your children, listen to your God, and renounce all your riches. Hear God’s truth from our lips, and set the godly example for us to follow.” Holy children, you are beloved by God your Father in heaven, and Saint Richard, the earthly father to whom you spoke truth in love. As we now sing in celebration of your family’s holy memory, intercede for us.

The text is in three sections: first, an alliterative sequence on “W” using the names of Richard’s children, followed by an alliterative sequence on “R.” The next section is an extended speech from Saints Winnebald, Willibald, and Walpurga, which adapts a quotation from the Latin hagiography, and employs parallel constructions such as “you dedicated us to Christ, but you devote yourself to the world all too eagerly.” The final section is a petition to the saintly children on the part of the faithful.

I composed prosomoia and the canon troparia for the model melodies common to the Byzantine chant system, with the idea that the cantor who knows those melodies will be able to sing the office whether or not they are an English speaker – much as those same melodies make it possible for non-Greek speakers to sing Greek prosomoia. In addition, the use of the common melodies can facilitate choral and congregational singing, if desired. To the extent possible, I referenced the standard versions of these melodies as published in Regopoulos’ edition of the Heirmologion of Ioannis Protopsaltis (keeping in mind that certain melodies represent a “collective wisdom,” so to speak, rather than a reliably strict model). Not all heirmoi I needed for the canon are published in Ioannis, however, and in some cases do not appear to be published at all. The Neon Heirmologion of Apostolos Papachristos, as well as the recordings found on the Greek Liturgical Texts online resource of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America served as additional references. For consistency and ease of use, where available I cited Fr. Seraphim Dedes’ English-language incipits of the automela and heirmoi as references on the score pages.

Even while composing for the meter, I nonetheless endeavored to keep syntax straightforward as much as possible. I think that English has a higher tolerance for poetic syntax in hymnography than others might; I’m not sure how one could pick up even the 1982 Episcopal Hymnal, let alone sing any of the traditional Christmas carols, and think otherwise. Regardless, my hope is that this office will be usable for singers in other repertories, and I am aware that poetic syntax is seen by some as a stumbling block in non-metered chant systems.

One point where I did not adhere to a specific choice consistently: “Sanctus Frigdianus” could be rendered any number of ways (indeed, it appears in Latin with various spellings), and it is not clear to me that there is a consistent enough English tradition to offer clear guidance. I mostly used “Saint Frigdian,” although when referring to his church in Lucca as a location, I referred to it as with the modern Italian “San Frediano.”

I preserved the Latin antiphon from Fr. Coens’ article as part of the office text, albeit in an altered form. The Latin text shifts sharply halfway through, which suggested to me the possibility of repurposing it as two separate idiomela. Thus, the first part is presented here as the idiomelon after Psalm 50 at Orthros, and the second is the Mode III Lity idiomelon, set respectively by Jessica Suchy-Pilalis and Fr. Seraphim Dedes. I have reworked them considerably from the initial literal, word-for-word translation so that they are more fitting for the current context.

A Greek adaptation of this office is probably not for me to write. However, I included a brief synaxarion reading in Greek.

For Psalm texts and the Canticles, I referenced the excellent, albeit as-yet unpublished, Psalter of Nicholas Roumas (who also kindly set one of the Lity idiomela).

Music: My intent, at least for an initial presentation, was to make available a set of scores that would be high-quality enough to allow either an experienced lone cantor or a full complement of antiphonal Byzantine choirs to sing services. As mentioned above, the prosomoia and canons were all written to be sung to existing standard melodies in the usual editions of the Byzantine Heirmologion. I set two short syllabic chants, the Glory after Psalm 50 – “At the intercessions of the God-crowned…” – and the Matins Prokeimenon.

Nine idiomela thus remained as I wrote the office – the Doxastikon at Lord I have cried, five at the Lity, the Doxastikon at the Aposticha, the idiomelon at “Have mercy on me…” after Psalm 50, and the Doxastikon at Lauds. Wanting the musical output to be as broadly representative of the current state of the art of Anglophone Byzantine chant as possible, rather than approach one composer to do all nine (or to attempt them all on my own), I commissioned eight different composers to do one apiece (and wrote one myself). The end result was a multi-generational and cross-jurisdictional effort, as the coalition of contributors have collectively been active at parishes in the GOA, AOCNA, and OCA, with a span of birth years from 1954 to 1992.

As mentioned above, the texts were also conceived as being compatible with other musical repertories. While I am not in a position myself to arrange the scores for a Saint Richard Vigil sung by a choir that is accustomed to, say, Obikhod chant or any other polyphonic repertory, I invite all who are in such a position to do so freely (for liturgical purposes at least; please contact me otherwise).

Liturgical execution: In February 2021, my priest agreed, at least in principle, to hold services for Saint Richard in 2022 if I could have service texts ready. In July 2021, I contacted the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lucca, Italy and the Diocese of Eichstätt to inform them of my efforts, share the current state of the work, and to see if there might be some way to request a relic for an All-Night Vigil. Some months later I received a letter from a Byzantine Catholic seminary in Eichstätt thanking me for letting them know, but the inquiry about the relic was sidestepped altogether. Ah well.

In September 2021, friends of mine in the Byzantine chant community started suggesting that I should send out a save the date notice if I really wanted to do an All-Night Vigil, since surely it would be the kind of event that people would want to come to and make a destination of. I did so, and a number of individuals accordingly indicated their intent to attend.

In October 2021, I had the lion’s share of the service written, and I started showing it to people I trusted for feedback, as well as to the composers I had in mind. In November, my priest agreed to an All-Night Vigil; wanting to process at the Lity with something other than an icon print, and with no relic being forthcoming, I commissioned a new panel icon of Saint Richard from Brian Whirledge, and I also started distributing texts to the composers.

I spent much of December and January scoring the Saint Richard prosomoia and canons in both Byzantine and staff notation. Given the range of musical abilities on the part of the individuals who had said they would be there, I also had to transcribe as much as possible into staff notation. Once the Saint Richard office was scored, I began assembling, and transcribing, scores in both Greek and English for the rest of the service.

My friend and colleague Peter George was of tremendous help with the service order. 7 February falls within the festal season of the Meeting of the Lord in the Temple, which dictates certain considerations regarding the Typikon. Peter gave excellent advice about how to handle these issues, while also helping address the practical matter of needing to be done within six hours while presenting all of the Saint Richard material in full.

In January 2022, when my parish held its annual cutting of the Vasilopita, I was blessed to find the coin. This, along with the semantic link between the names Basil and Richard that I was already exploring in the hymnographic text, inspired an idea: again, if the objective was to promote popular commemoration of Saint Richard among today’s faithful, then perhaps introducing the custom of a festal food would also be a worthwhile effort. My first thought, again with an eye towards the semantic equivalence of Richard and Basil, was to bake a “King Cake,” such as is the historic tradition for Twelfth Night/Epiphany Eve in the West (and which is also popular for Mardi Gras in the Gulf Coast region). My wife talked me out of that idea for her own reasons, but seemed to think the impulse was likely right. We explored different options that would nod to various geographies represented in Saint Richard’s life – plum pudding for England, panettone for Italy, and so on.

A St. Richard Pilgrim’s Staff

As with the hymnography, the imagery employed in Saint Richard’s life provided key inspiration – namely, his setting aside his royal sceptre for a pilgrim’s staff. This image led us to Hefestangen, a braided German bread sweetened with dried fruit. I modified this recipe slightly by mixing in candied fruit with the raisins and soaking them in rum, and then shaped it like a staff. The test loaf was promising, and I baked three staves that my priest decided to bless at the Artoklasia with the five artos loaves. They were distributed after the Vigil, and they were very well-received; my instinct appeared to have served Saint Richard well.

The service itself was almost the victim of weather. A major winter storm hit on Friday, 4 February 2022, causing O’Hare Airport to cancel all flights for the day. Miraculously, however, everybody arrived safely in Boston, and we assembled at Dormition with 11 people on each side in the choirs and three priests at the altar.

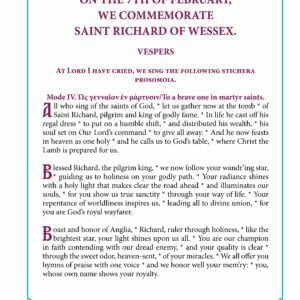

We began at 6pm with a censing of the church while the right choir sang a slow setting of Psalm 5:7 (LXX), “I will come into your house…” Vespers, with full Anoixantaria (the singing of the last ten verses of Ps103 with Trinitarian tropes and refrain), a slow setting of “Lord, I have cried,” all of the psalm verses (unusual in a Greek parish), festal Prophecies, Lity and Artoklasia with 7 idiomela, and a festal reading of the Saint’s life, took approximately two hours and fifteen minutes. Matins, with a brief setting of Ps134 for the Polyeleos, the complete canon for Saint Richard, slow settings of the katavasiae for Odes 1, 3 and 9 of the canon, and all of the psalm verses at Lauds (again, uncommon in Greek practice), was about an hour and forty-five minutes. Divine Liturgy, with proper concelebration rubrics for the Trisagion as well as a full Dynamis and Alleluiarion before the Gospel reading, was about an hour and twenty minutes, and the clergy were distributing antidoron by 11:20pm. The teamwork at the altar working in concert with choirs of attentive, experienced singers facilitated the flow of the services very well, and there were no dead spots. The one moment of uncertainty came in Vespers, when we were not clear ahead of time if the clergy would process to the narthex for Lity or simply return to the solea; at Fr. Romanos Karanos’ direction, we went to the narthex.

Clergy, choirs, and congregation in Dormition’s narthex during the Lity. The panel icon of St. Richard is on the analogion.

The non-Saint Richard material was balanced roughly half and half between Greek and English. The general rule at Dormition is for the choirs to pick up in whatever language the clergy leave off with, and this seemed reasonably instinctive to the choirs to follow, even with out of town guests.

The future: I am hopeful that an initial service at a neighborhood parish in Greater Boston represents a starting point rather than an endpoint for future veneration of St. Richard of Wessex. Whether or not that means the materials I’ve discussed here themselves have a life beyond 2022 is a separate question; surely it would not be difficult for a better hymnographer to produce something more fitting if they were so inclined.

That said, certainly Dormition in Somerville will have another All-Night Vigil for St. Richard in 2023, even if it doesn’t include the luxury casting in all of its particulars that we had this year. As well, there have already been individuals who have contacted me about serving this office, at least in some form, at their own parish, including somebody at an OCA parish who wants to arrange it for their musical repertories. May their efforts be blessed!

I am also currently preparing the St. Richard office and scores for publication. I have no details I can share yet about when it might be completed or available, but I can share some excerpts from the in-progress draft:

I also hope that eventually there will be a recording of the office chants that can serve as a reasonable model for execution; my ideal would be to reproduce the antiphonal mixed choirs that we had earlier this year, but we’ll see what might be possible.

In conclusion, I find it relevant that Saint Richard’s journey was intended to take him from the western edge of the eighth century world eastward to Jerusalem — what we may now think of as part of the Middle East but was, within that frame of reference, depicted as the center. To that end, I would like to think of this office as an attempt to draw devotion to Saint Richard in an ostensibly eastward direction, making his veneration accessible as it were to Christians in Greece, Russia, Lebanon, and so on, while also creating an opportunity for all Orthodox Christians to commemorate him in what I hope will be a mutually intelligible fashion. And, in all of this, also acknowledging that the draw is truly towards Christ as the center.

Δόξα τῷ Θεῷ πάντων ἕνεκεν! Glory to God for all things! Saint Richard of Wessex, pray for us!

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Any chance you could update that Dropbox link so that it’s not routed through Facebook (for us Facebook non-users)?

Oh, sure, didn’t realize it was doing that. Try it now.

I love it! It is wonderful to see Orthodoxy reconnecting with her western preschism saints.

Perhaps one day “the last Orthodox king of England” – Harold Godwinson – can be glorified and honored in such a way!

It would be worth doing! Also, as an Anglo-Dane in an eparchy of the EP, I sometimes half-jokingly refer to myself as a member of the Varangian Guard; I just discovered that there is a saint named Theodore the Varangian. My son is named Theodore after St. Theodore the General; maybe that’s worth considering, too.

I also have an idea for St. Patrick. There are various iterations of offices for him, but nothing in English that really corresponds to what I’ve done for St. Richard, not in the same way. We’ll see.

Congratulations Richard on your liturgical composition and many thanks indeed for your very helpful contextual essay. For your interest, Monk Isaac (Lambertson) of pious memory composed a service to St Theodore the Varangian and his son John. This would obviously be written according to the Slavic Ustav and musical melodies. With regards to St Patrick, a slavonic service was written by Valeria Hoecke which was translated by Fr Joseph.

Christ is risen! Thank you for your kind words. It’s great to know about Monk Isaac’s work for St. Theodore; and yes, I’m aware of various versions of an office for St. Patrick. I think the difference of approach with respect to composition and target repertory leaves some room for other versions. What I’m sketching out now as a starting point for a canon to St. Patrick, for example, adapts a portion of the Lorica for the first troparion of each ode, metered to the heirmoi of Great Paraklesis. We’ll see how it turns out.