Similar Posts

Ethiopian Christianity presents many mysteries to us, their unique use of Old Testament typology, their concentric churches, their claim of having the Ark of the Covenent and its use in liturgy – these all create an obscure but fascinating question. I went to Ethiopia in 2009 to discover more about their liturgical arts. I would like to share some of my findings with you. This is just to give you a taste since of course one could easily write a book on the subject. I will focus on the Lake Tana churches and mostly one church : Kidana Mhiret on Lake Tana.

First: The Ark

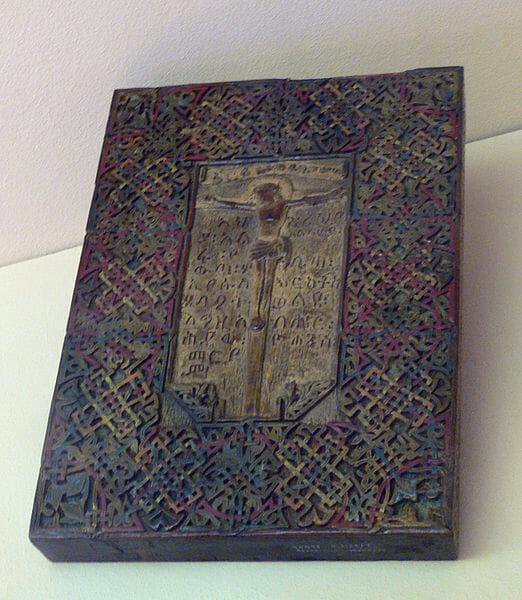

For those who still do not know, Ethiopians claim to have the Ark of the Covenent, which according to their tradition, was stolen by the son of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and brought to Ethiopia. Still according to their traditions, when they converted to Christianity, the Ark continued to play a central role in their worship. The fabled Ark is in a small chapel in Aksum, but each church has a symbolic reproduction of the Ark, a carved box which resembles a table and has inside symbolic reproductions of the tablets of the Law (some of which are actually icons, interestingly enough), which are the sacred center of the church, much like a relic in the altar would be for us. Sometimes the word “tabot” can be used interchangibly to refer to the box or the tablets inside, which can be confusing.

Lake Tana and the Centrally planned churches.

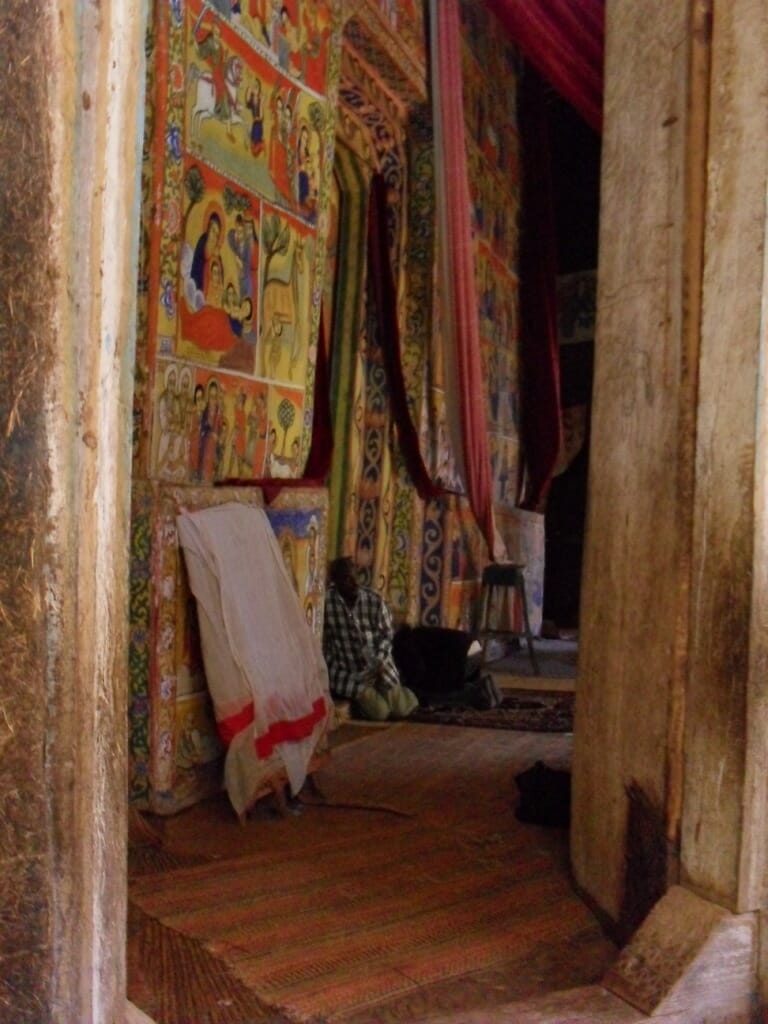

The lake Tana Churches, which belong to monasteries on various islands, are some of the most fascinating for an icon lover. Basically wooden huts, they are round in shape with a square building inside. The largest is Kidane Mhiret.

Ethiopian Chruches are like most traditional churches, separated into three main sections, an outer entrance (vestibule), an inner part (nave) and the most inner part (sanctuary) which they call the Holy of Holies. Different from our tradition, during services, the faithful stand in the outer court (A) until those who are going to take communion may enter(B), but outside of services, the faithful enter and venerate the “holy of holies”. The square building inside acts very much as an iconostasis, covered in icons, it hides the holy of holies from view.

It has three doors, one at the three directions, west, north, south, and the eastern wall only has windows that are opened during services. So as we can see, although centrally planned, the churches are still facing east. And with the doors on three sides, one is reminded of the iconostasis described in Hagia Sophia during the time of Justinian, a model of which was reproduced recently in the US at New Skete in Cambridge, New York.

Southern Door

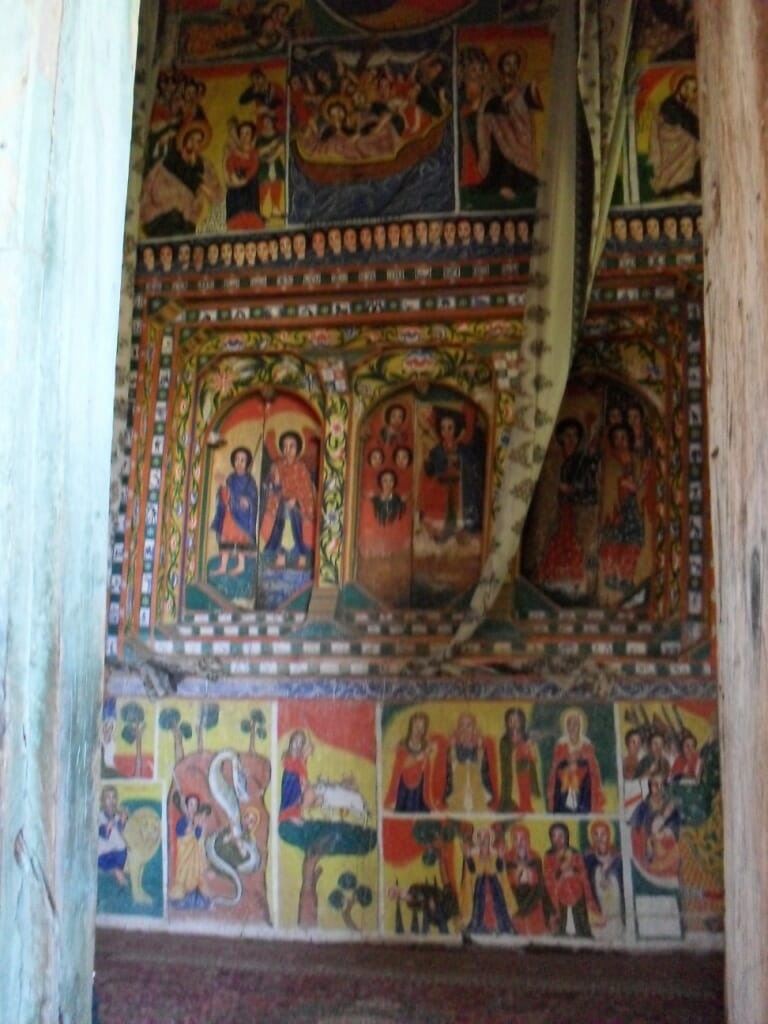

Each wall seems to have at least some semblance of an iconographic programme, although things cross and bleed into each other (and I do not have the pretension of understanding all these images). The Western doors (like our holy doors) are where clergy take communion and show the death and resurrection of Christ.

Like in all Myaphisite churches, men and women are separated, with men on the Northern side and women on the southern side (opposite of Greek and Russian tradition), and the iconography seems to reflect this.

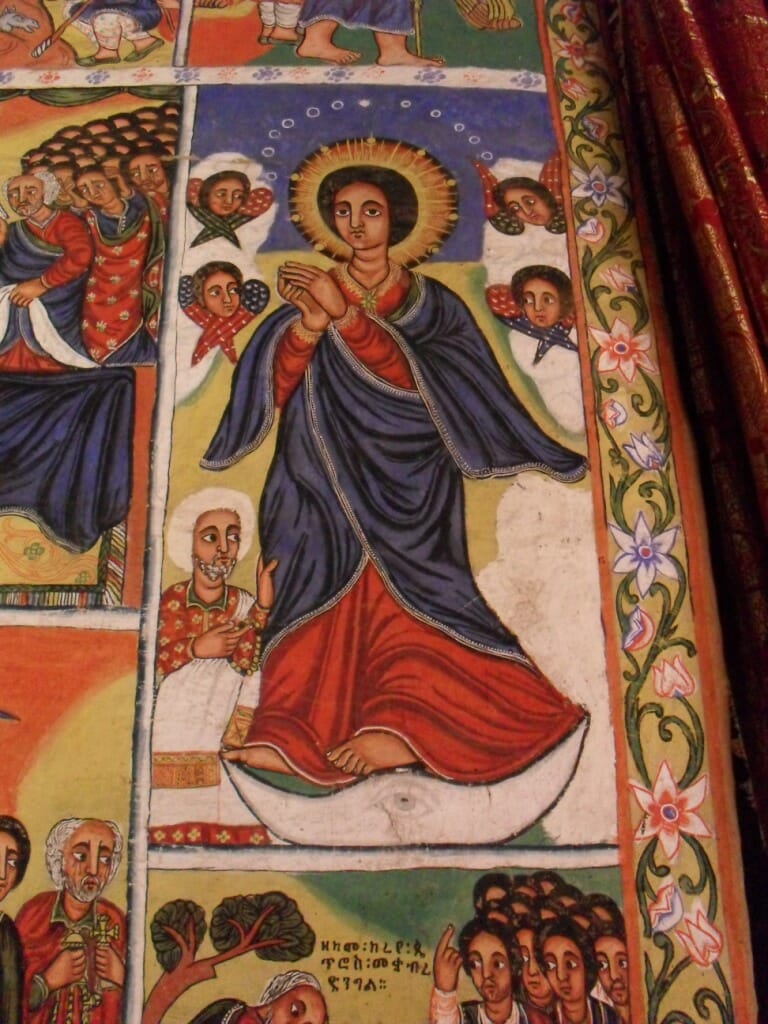

On the Northern side, we find the Warrior Saints and holy martyrs. On the doors are the Archangels Michael (left) and Gabriel (right). Gabriel is spearing a giant fish that is said to have been disturbing the monastery long ago. On the Southern side are life and the Miracles of Mary taken from tradition.

On the Eastern wall are mostly the miracles of Christ, but also images of the main Ethiopian Saints.

Western influence.

In the 17th century, a king of Ethiopia converted to Catholicism through Jesuit influence. His son returned to Orthodoxy, but it seems that western imagery left a permanent mark, as many later western types entered the canon with an Ethiopian flavour.

Extreme Iconography

Ethiopian iconography is not shy in its imagery. Many of the images seen in churches can seem shocking to us. It is full of graphic violence and emphasis on obscure stories from tradition . We are not accustomed to seeing images of St. John the Baptist as a baby trying to feed from his mother’s dead body and then being suckled by a gazelle.

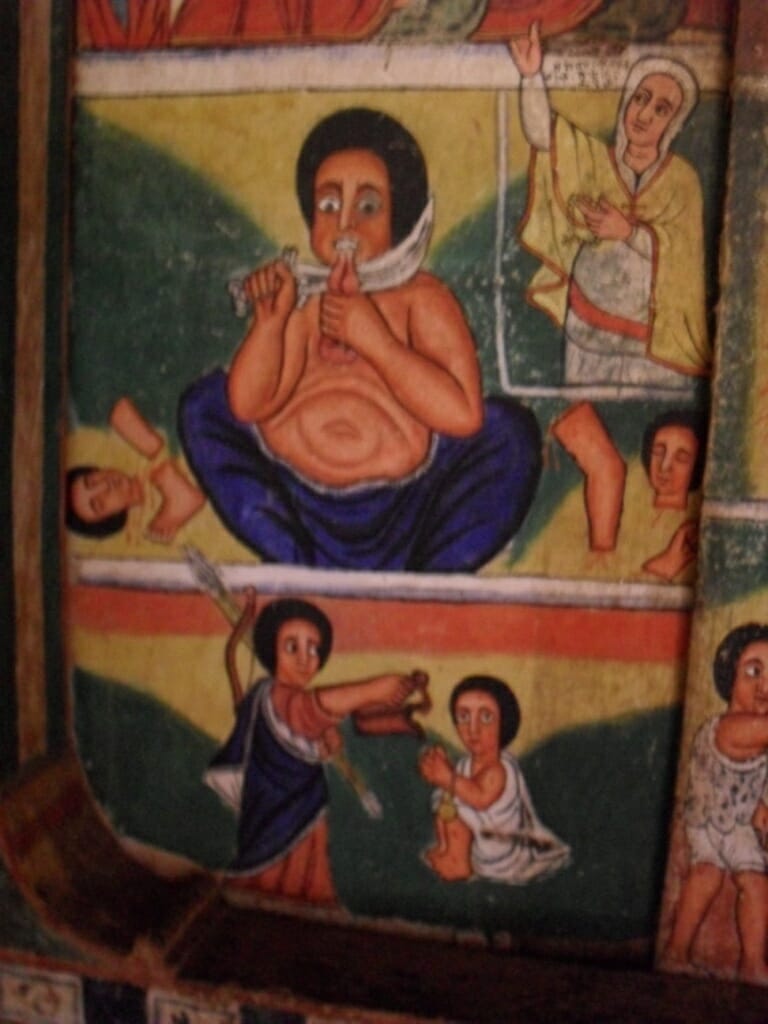

Nor are we accustomed to seeing the young Christ changing an African servant into a monkey yet these types of images abound in Ethiopian Iconography. Even their most famous saints have stories that revel in the extreme, the grotesque and the almost magical. From a saint that committed suicide to imitate Christ’s suffering to a desert hermit who out of love for a bird dying of thirst, gave it to drink out of his own eye, the exception is the norm. The most extreme image, which appears on the doors of the southern wall is that of Belai the Cannibal, shown eating human flesh, who through an act of mercy of the Holy Virgin was admitted into heaven after having given water to a hermit in the desert who had asked in the “name of the Virgin Mary”.

These are only but a few examples, but I think the surprising, extreme and miracle-flled images of Ethiopia are a testimony to its own extreme and wondrous story, the surprising resistance of a unique version of Orthodox Christianity, much isolated from the rest of Christianity for such a long time.

But even after visiting Ethiopia, there is still much of it that remains mysterious to me.

(For those who wish to see more images of this trip, I have posted a gallery with chronological descriptions on my facebook page: http://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.216291877408.130352.591817408&type=3&l=4e3e2b90a9