Similar Posts

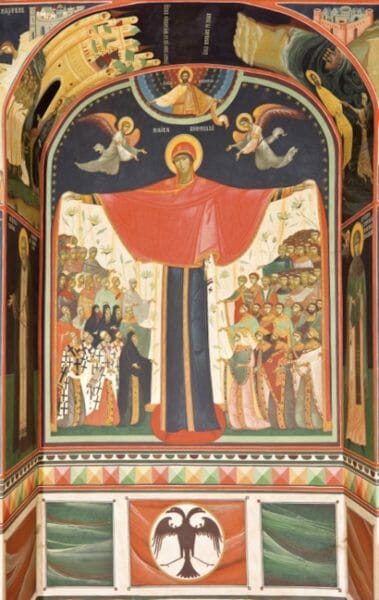

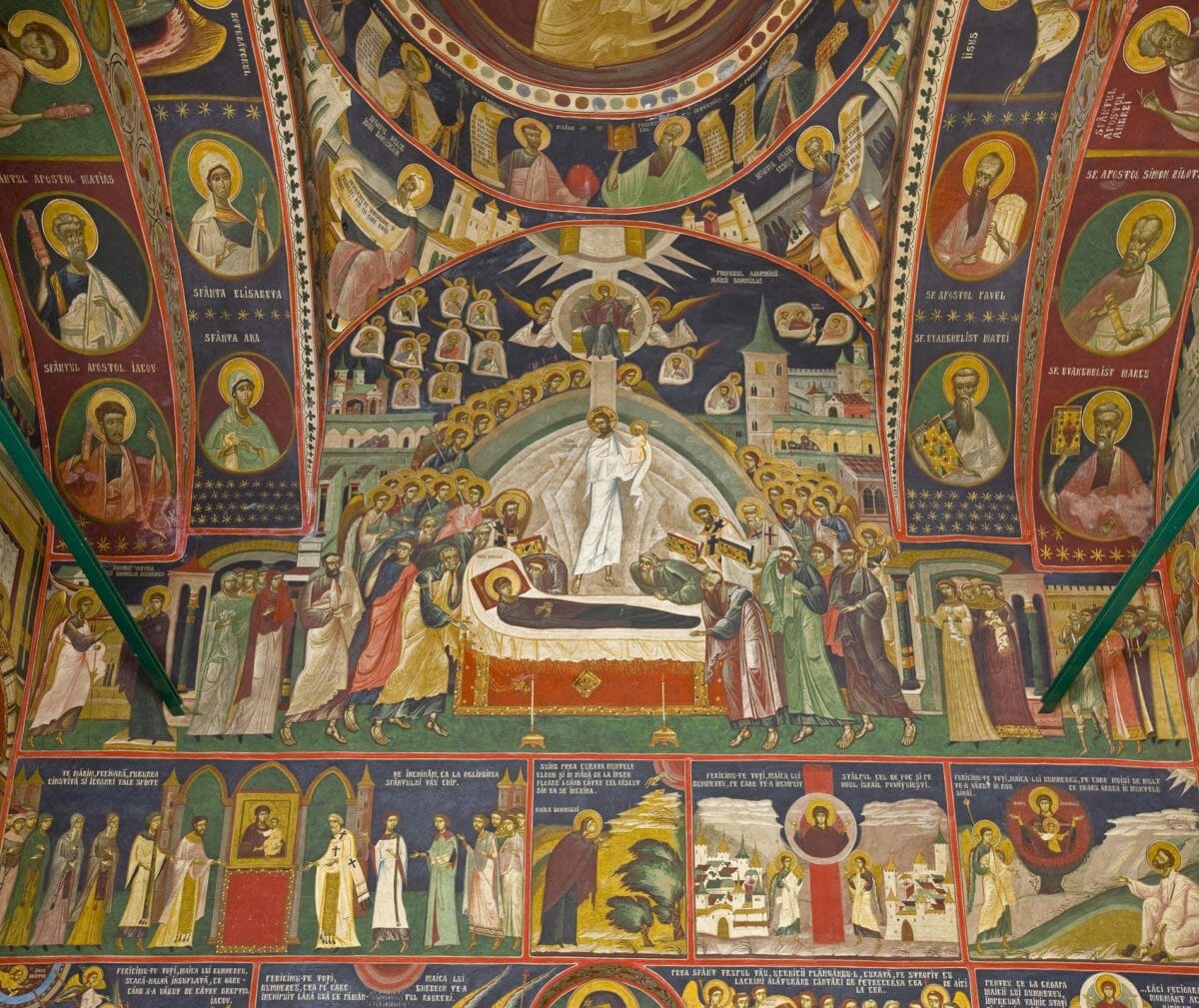

The monastery church of the Holy Apostles and the Dormition of the Mother of God in Râmeţ – painted by Grigore Popescu

The divine depths of the Beautiful, the Good and the True do not have a static manifestation in our sublunar sphere, in History. There are times of retreat, when the cultural landscape may be likened to a desert, devoid of beauty; when a space larger than a country can turn into a gloomy prison. Ash and molten lead seemed to flow over the countries of Eastern Europe during the communist period, and Romania had a full share of this demonic torrent.

In fact, the Christian message expressed through appropriate images – which indicate the eschaton and the parousia – was lost to us prior to communism’s appearance. This happened before the beginning of the 20th century, because authentic iconography had remained devoid of craftsmen. I will shortly return to the historical path of the holy image in Romania immediately below.

Bright times are not missing from History either, but they seem shorter, like the passage of an unexpected bright star or comet through the night sky. What started as an amazing revival can fizzle out after a short time. Or it can give rise to a longer-lasting movement.

The iconographic revival in Romania has been talked about before in the pages of this journal1. Now I would like to present the work of the mural painter Grigore Popescu-Muscel (born November 23, 1945). I believe his work to be the most consistent link artistically, but also quantitatively, among three periods of Romanian iconography: the period before the beginning of the twentieth century; then the period of searching for a Byzantine expression of mural painting during twentieth century; and finally, the new Romanian iconography – a group of icon and church mural painters who are today in their forties. His output includes restoration, new murals in over 50 churches in Romania and abroad, and icons on wood (plus easel painting).

I conceived this essay in three main parts, each with sub-sections:

The First Part (this article) is a short overview of the work and life of this Romanian iconographer, Grigore Popescu.

The Second Part will present and analyze the iconography his final work, in the Cathedral of the Nativity in Brăila, a city along the Danube in Eastern Romania. I did not choose the Brăila cathedral by chance. It is now nearing completion, and is his most recent work for us to consider. The dimensions of the holy place permitted a program of holy images revealing the vast experience accumulated over the years of his career. I believe this will remain as an important chapter of European art history.

The Third Part is meant to expose the international public to the quality and scope of his entire body of work. The master Grigore Popescu turned 77 in 2022, and the Lord still sustains him as a vital and creative person. In this section of the essay I will reveal some landmarks that stand out from his entire career: the metropolitan church in Nürenberg, the central church of the Lainici monastery, the baptistry in Iași, the small church of the museum under the cathedral of Iași, the church of the king Stephan the Great from Borzești, the church St. Nicholas in Câmpina, etc.

General characteristics of the mural painting of Grigore Popescu-Muscel:

Master Grigore Popescu (b. 1945) does not work with large teams. His constant helper over the years has been his wife, Maria Popescu-Dragomir (b. 1954), muralist, restorer and icon painter. A very small team of apprentices has accompanied him during his last working years.

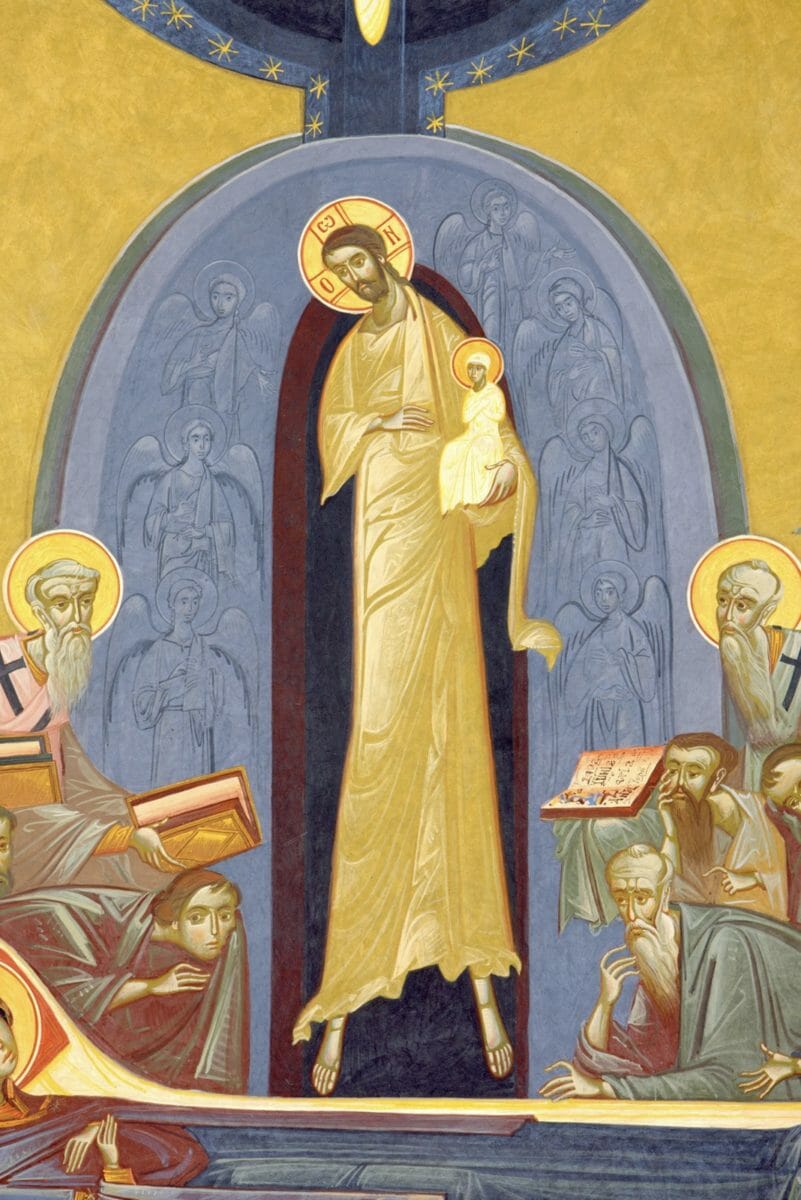

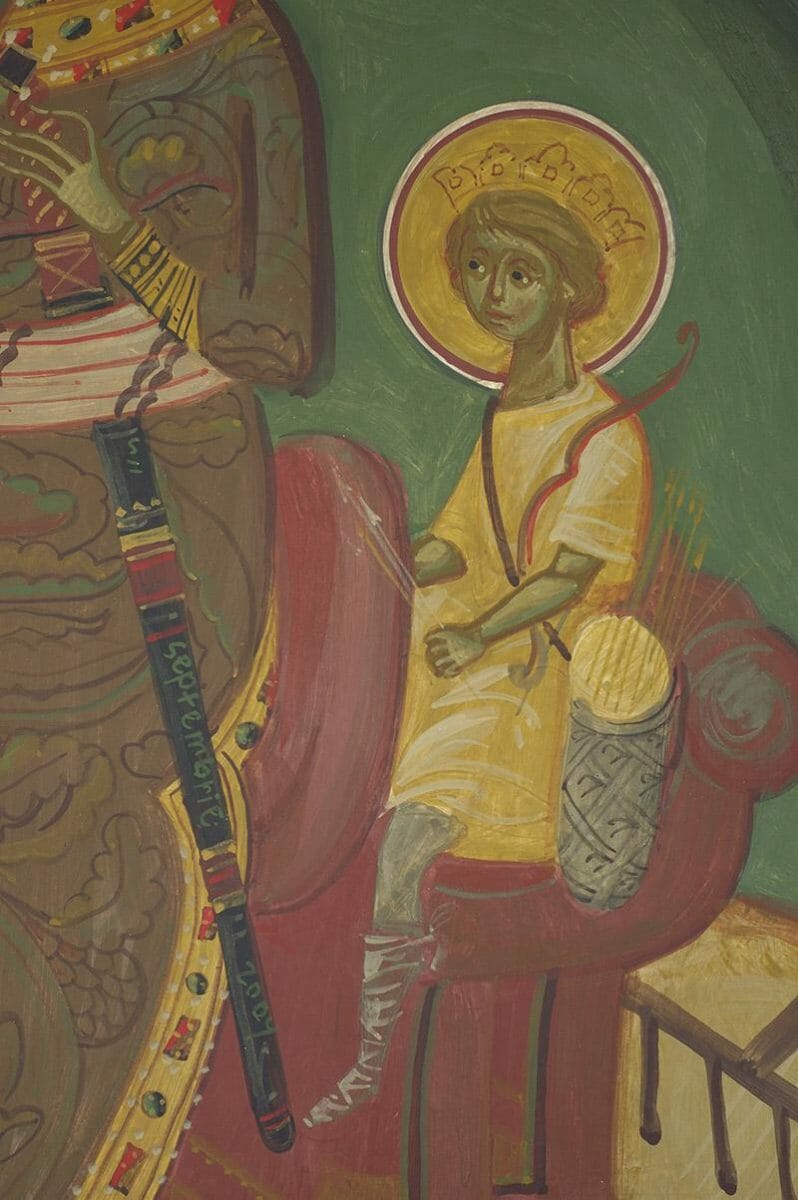

The first feature that cannot escape even a casual glance from the viewer are the elongated silhouettes, in which the natural proportions, the ratio between the size of the head and that of the body, are completely left behind: these eschatological bodies can encompass more than 9 – 10 times the length of the head.

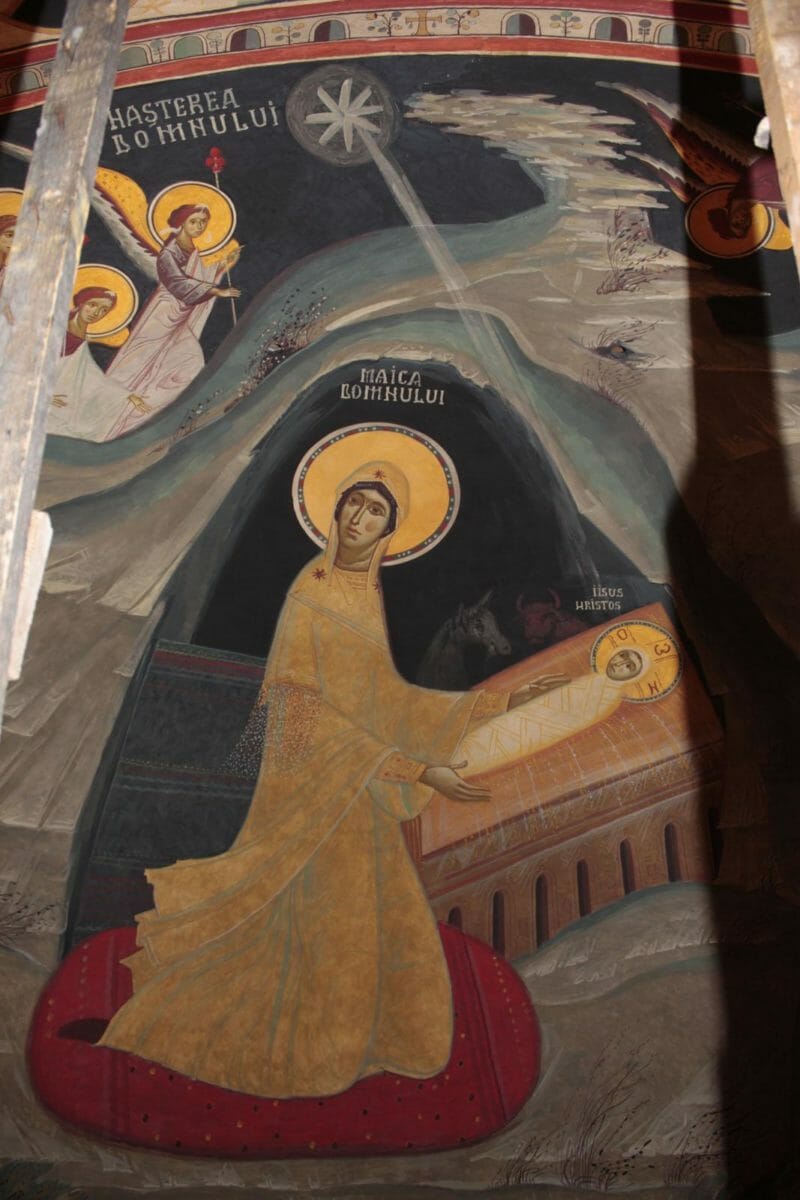

Secondly, the corporeality of Christ, of the Mother of God, of the saints and of the angels is revealed through what I would call a reverse perspective in a generalized sense, i.e. not a simple changed optical perspective, but all those elements that transfigure the person and the painted scene from a mundane one to one of the eschatological Kingdom. Thus, the silhouettes are drawn with an elegant and graceful touch; they do not have typical shapes (prominent musculature in men; hips or breasts in women). One remarkable feature is the way they actually detach from the ground, with the elevated heels, on the tips of toes; a posture that seems to indicate a celestial ballet or the lack of gravity.

Other elements include the large eyes, reminiscent of the Fayum paintings, and the rosy cheeks which seem borrowed from popular Romanian icons painted on glass. Sometimes the silhouettes, the face, the clothes are sketched only from a few lines, other times they are elaborately worked out, depending on the importance of the character and the scene. But the minimalism of the lines gives maximum expressiveness.

Another inverse element that can be encountered sometimes is the unusual position of the head, which violates any anatomical determination: its elongated oval being placed perpendicular to the neck; likewise unnaturally elongated arms. Anatomy is violated in different ways to express a state, a relationship. I have no doubt that many painters who are used to a faithful rendering of the human person feel uncomfortable looking at a body thus transfigured.

No one element characterizes Grigore Popescu’s style, and this master of mural painting is not the only iconographer to use them. They are found in what we broadly call Byzantine painting. However, all of them together, uniquely combined in each location, give an unmistakable imprint of this painter.

Compared to Georgios Kordis who constructs faces and silhouettes, the composition of a scene, through axes and helping geometric shapes, Grigore Popescu seems the complementary type, for whom the organicity of the complex form, drawn ‘at once’, matters more, even if it means less than perfect lines (straight lines, curves or circles). They give the characters a less frozen hieratic character, more alive, the “sacredness” being obtained by other means (elongated silhouettes, etc.).

Aesthetic beauty is not necessarily an end in itself; what is important is the message, the meaning conveyed. I remember a saying of the Romanian poet Nichita Stănescu (1933 – 1983) “the gaze cannot linger long on an impeccable geometric cube”. If, however, a corner is cut out, chipped, the viewer will stop and exclaim: ‘How perfect it could have been!’ Living organicity is therefore preferred to abstraction or perfect geometrical forms.

The angel appearing to Moses in the Burning Bush, the Baptistery under the Metropolitan Cathedral, Iași

Mother Atanasia (Stavropoloes Monastery, Bucharest), who trained as an art historian, characterizes the iconographer in a recent article2. Grigore Popescu-Muscel is presented as the most important connection between those who tried to recover Byzantine fresco painting, lost by the end of the 19th century, and, on the other hand, a new generation of mural painters from Romania, a period of around 40 years3. What her article captures well is the artists searching for a neo-Byzantine style; freedom from the influence of secular painting; the acquisition of a local-national imprint; and development of a creative personality (of the painter himself). The first person in whom all these ideals were embodied is master Grigore Popescu. His work that began in the 1970s (the Flamânda church in Bucharest, a large work of renovation and repainting, was between 1983-1986)4, today has reached over 50 restored or newly painted churches, and also includes all areas of Romania, and portions of Hungary, Germany, Cyprus, and France.

Turning to color, we can start with the background of the frescoes. Often the prepared wall helps the final effect, through application of a thin, transparent layer of color. The brushwork may be deliberately visible or not. Often the intended impression is that of antiquity, achieved by means of muted colors and certain shades. We could say that the iconographer avoids colors that are too bright, but this does not mean that we do not also encounter scenes where stronger colors dominate, not bright like a lollipop, but impactful. To suggest the Kingdom of Heaven, the background often bears numerous stars.

It is difficult for me to globally characterize the color palette used by Grigore Popescu because, as in the case of the choice of the iconographic program, of the themes, it depends on the specific location and the surrounding context of the scenes. Not only does each church have its own being, but each scene, even each detail, is painted with the care of a unique meaning that avoids repetition.

Undoubtedly, he presents an unusual harmony of colors – born from long practice and excersize. These colors can be combined in harmony, but also in contrasts. Sometimes only one dominant color appears, other times there may be two dominants, plus subordinate colors. The painter, according to his own confession, was not born at the level of maturity he is now. He is not shy about saying that he is sometimes embarrassed by the imperfections of the past. Quality is acquired through long practice and experimentation. The statement ‘only after the fifth painted church you can understand what it means to dress a place of worship in images’ might scare the young artist. That’s why we recommend patience, permanent lively, non-standard interest, endurance, confidence in your own ability to evolve and … humility.

As we will see in the case of the rhythm of forms, the coloration of a character, of a scene, should not be repeated for convenience, but only if the repetition has a meaning. If all the silhouettes of the saints are oriented in the same direction, as is the case in certain old Russian iconographic programs, the gaze scrolls without stopping over each face, out of monotony. Saints do not acquire a personality of their own in this way. Which does not mean that originality must be sought at all costs. This is not the purpose of church art, but personalized treatment, harmony through rhythm and rhythm breaking. In Brăila, in the register of military saints in the northern apse, the orientation of all the silhouettes towards the altar is broken by the two saints Theodore (Tyron and Stratilat), facing each other, who look up, where Christ appears once more painted in the heavens.

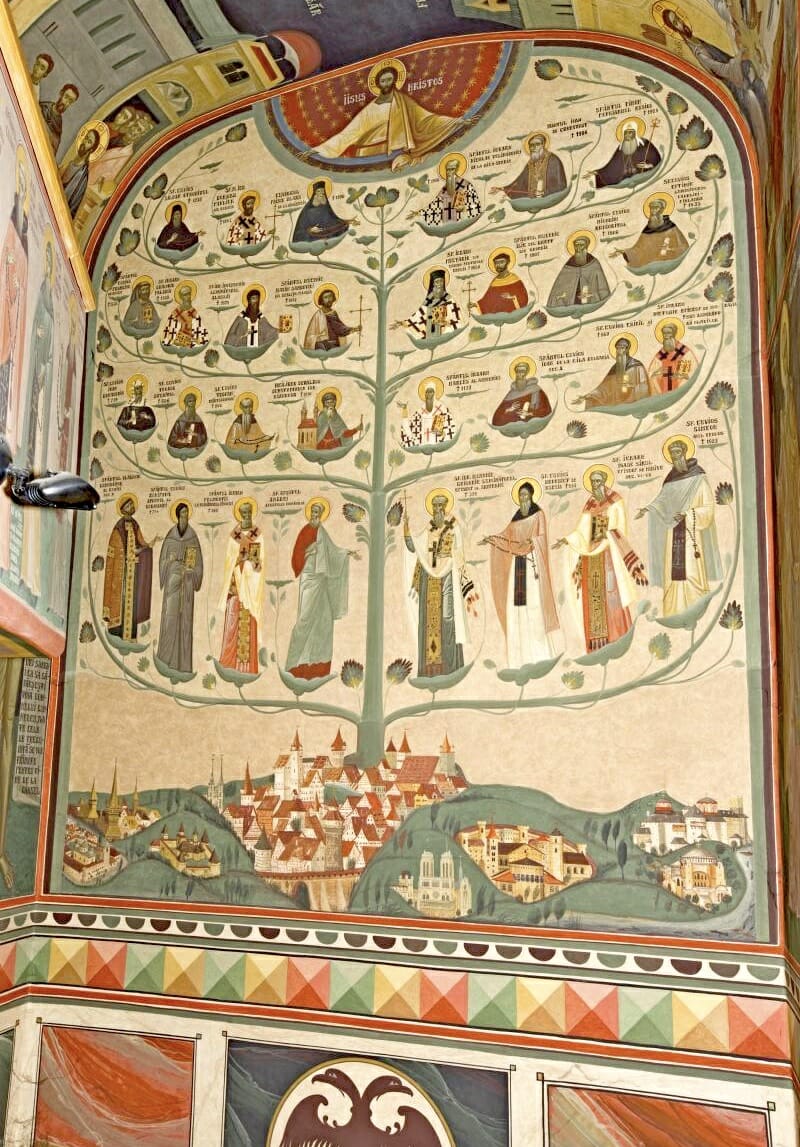

The iconographic program as a whole has, of course, some fixed landmarks and it is useful to have a normative canon of it, such as the case of Ene Braniște’s program5 published separately by the Patriarchate of the Romanian Church in order to avoid the cases of deviation that appeared due to the multiplication of icon painters, some with the desire to push their artistic creativity too hard. But an iconographer of long experience, who has intimately assimilated countless sub-traditions of Byzantine iconography, knows that the meaning of the place, the architecture and the ingenuity of the painter to find solutions will have the final say over any standardized model.

An experienced painter who no longer risks slips or deviations; who researches a place for months before the actual painting, can afford what from the outside seem like simple liberties. Creativity, however, is not the fruit of pure fantasy, but the fitting with experienced skill of the painting to concrete requirements (history and significance of a location; a city church has a different destiny than a hesychast monastery; architectural constraints).

In general, the painter avoids crowding the scenes or excessive ornamentation: “abundance leads to a saturation and a dilution of the aesthetic”. It is a line followed, if not in antithesis, at least more airy compared to some achievements of the tradition. For example, compare the wall painting from Sucevița (the XVIth century), northern Moldova (below) with the eastern wall of the altar, Brăila (above).

There are numerous themes adopted (but not copied) from the tradition and put to good use. For example, from the painter/saint Pârvu Mutu (1657 – 1735), with whom Grigore Popescu shares his birthplace, is adopted the theme of St. John the Baptist being carried by an angel in the desert. This scene is on a pendentive of the exterior porch of the Colțea church in the center of Bucharest and is painted in its own versions in Borzești and Iași6. Another theme of master Popescu-Muscel, painted repeatedly, is the rejection of communion by the apostle Judas compared to its reception by the other apostles.

The great innovative theme that makes its appearance in several churches is the transformation of Jesse’ tree into a tree of the saints (it is found in Nürenberg, Lainici, and, as we will see, it acquires an unusual rich formula in Brăila).

It may be worth noting that a main scene, for example the Resurrection or the Nativity, etc., cannot be thought of in isolation from the scenes surrounding it. There are cases among painters with less experience or patience to find other solutions – where a certain scene is placed in an iconographic context with which it has no direct relations. I now think of the empty throne (etymasia) placed in isolation and far below the highest register of the Origin of the Last Judgment. Many examples may be cited of this fault.

Let’s consider the testimony of Grigore Popescu himself: it can take months to do the documentary research of the place, create a rough, preliminary design of the iconographic program, choose quality materials, and organize the site, all before the start of work.

The last dimension of the iconography that we present here is the decorative elements. Whether it is floral elements, geometric elements, old Christian symbols or text, Grigore Popescu’s mural painting includes an endless richness of items, which we promise to deal with separately in the future. They are inspired by the most diverse sources, both native folk art and universal painting, and are meant to delight; to suggest meanings (such as an Edenic field); to separate the painted scenes and not to leave bare those spaces that cannot be filled with icons (wall space below the waist of the viewer or small architectural gaps where characters do not enter). But they also appear in the scenes, especially in the decoration of the clothes, ornaments, weapons of the people represented.

Before I end this series of reflections, I must also mention one more thing that is learned on a painting site: painting on the wall, more than other types of painting, requires technique, craft, yes but also physical robustness – ability to climb and descend from ladders, paint over one’s head, etc.

As for the technique, it starts with the artful and knowledgeable choice of materials, which must not only provide the intended visual effect, but must last. If the painting does not last 100 years, 300 years, it can reproduce eternity, but it does not last in it. Then on the scaffold you have to stand sometimes at dizzying heights, in uncomfortable positions, the al fresco technique, does not allow you time to rest, it cannot dry, which requires a strong, attentive, determined and healthy psycho-physical nature.

I will end this section with the following thought addressed to any icon and mural painter: The Beautiful instantiated in fresco is that ‘quantity’ of the Eternal Beauty that a particular painter, here the master Grigore Popescu, can actualize first in his own soul, then on the wall, in the murky waters of sublunar human life.

Biographical data of the painter:

Grigore Popescu-Muscel was born on November 23rd, 1945 in Romania, Câmpulung-Muscel, in a family of intellectuals: his father graduated in theology and letters, and did translations from ancient Greek. His mother was a teacher of mathematics and physics. He is married to Maria Popescu Dragomir, who is also a restorer and painter. They have been working together since 1979-1980 when they began at the church of St. Archangels Mihail and Gavril in Zorile, Caraș-Severin county, Romania. To this day the two are inseparable in life and work.

He did his first internship as a young apprentice in 1966 at the key monument of the Orthodox tradition, the princely church at Curtea de Argeș, under the guidance of the restorer and painter Arutiun Avakian, whom he would then accompany on several construction sites. Since 1970 he has been certified as a mural painter, and since 1974 as a restorer painter.

In 2022, Grigore Popescu-Muscel received the highest award from three institutions from Romania – UNAGE Iași, the Metropolis of Moldavia and Bucovina and the City Hall of Iași – for his entire activity.

An overview of recent his recent works is provided on the Doxologia website dedicated to iconographer: https://doxologia.ro/pictorul-grigore-popescu-muscel. At the bottom of the page there are small collections of photos from some of the painted churches. The painter’s personal page is www.murala.ro Here you can follow the icon painter’s activity by period: click on Curriculum, then on the subordinate headings that open. The interested person can then look at a series of images divided into categories:

- Murals (with 12 subcategories, i.e. 12 mini-collections of photos from 12 painted places)

- Iconostasis

- Easel painting

- Restoration

- Icons

- Sketches

- Drawings

Visitors to this page can choose between Romanian, English, Greek, Russian, German or French languages for the opinions about the painter’s work.

Additional images of Popescu’s mural painting:

Endnotes

1 See the entry in the Orthodox Arts Journal The New Romanian Masters: Innovative Iconography in the Matrix of Tradition.

2 In Romanian: Monahia Atanasia Văetiși, ‘Pentru o erminie a picturii bisericești în modernitate (1900 – 2021). Iconografie și stil: de la Art Nouveau și neoromânesc la arta bisericească contemporană’, în Lucrările Conferinței Naționale: Unitatea dogmatică și specific național în pictura bisericească, Basilica, București, 2022, pp. 47 – 75. In English: Nun Atanasia Văetiși, ‘For an hermeneutics of church painting in modernity (1900 – 2021). Iconography and style: from Art Nouveau and Neo-Romanian style to contemporary church art’, in Proceedings of the National Conference: Dogmatic unity and national specificity in church painting.

3 Some of them being mentioned in the essay by Jonathan Pageau ‘The New Romanian Masters: Innovative Iconography in the Matrix of Tradition’ (OAJ, March 2015).

4 It remains an iconographic landmark to visit in the center of Bucharest, although hidden in a small street behind the old Patriarchy.

5 Ene Braniște (1913 – 1984) is the most important Romanian liturgist theologian.

6 Vasile Tudor draws attention to this origin of the theme in the study mentioned in the final bibliography, pp. 111-112. The above lines are indebted to the second half of his book.

If you enjoyed this article, please use the PayPal button below to donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

I think he is the greatest contemporary iconographer. A true gift for the iconographic tradition and, for those who look closely, a teacher for future generations. Thanks for this first part of your article.

Thank you so much for writing this article, I have been hoping for something like this for a long time!