Similar Posts

Services for the Departed is anticipated in print in early 2013!

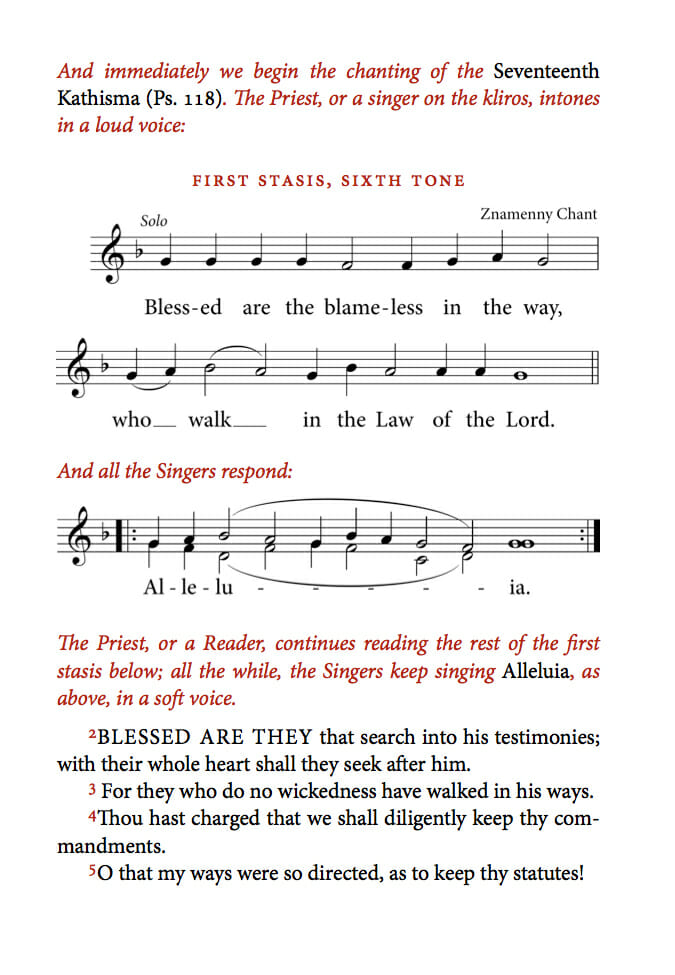

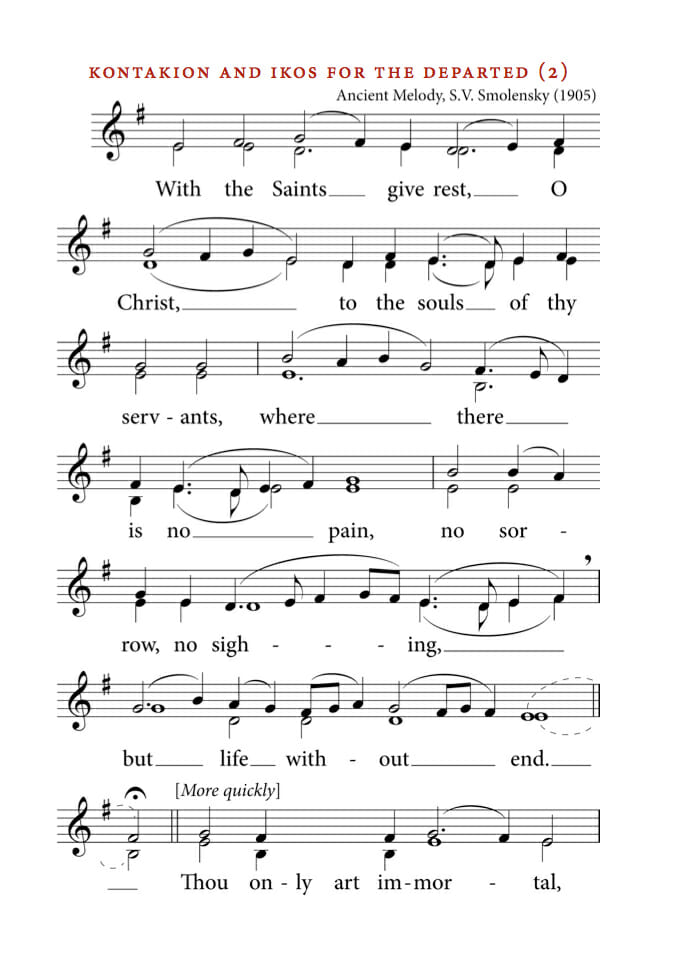

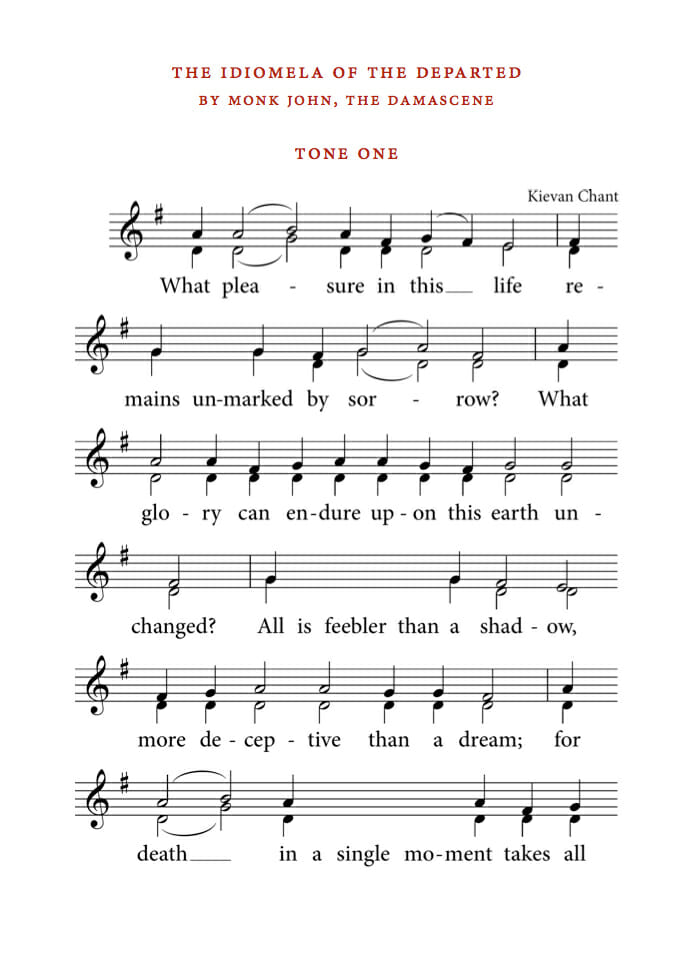

With this volume, we offer to the English-speaking Orthodox world music for the Panikhida and Burial services based entirely on melodies from authentic Russian chant originals, something that heretofore has not existed in English in any one volume. Furthermore, we have endeavored to present these chants in a form that is at once satisfactorily singable by either a single chanter or a small group of amateur singers, but is still musically rich and uplifting, in keeping with the sober yet joyful character of all traditional Orthodox liturgical chant.

From the introduction to the book:

Over the more than one thousand year tradition of Slavonic liturgical music much of the field has been dominated by what is commonly known as znamenny chant. Znamenny chant — a term that means “signed” or “neumed” chant, referring to the fact that the chant melodies were composed and notated rather than transmitted aurally — is regarded today by Russian Orthodox as the foundation of Russian liturgical music and the main form of canonical chant. Over the course of time a number of variant forms of znamenny chant developed, such as demestvenny chant, Kievan chant, Lesser znamenny chant, and others, but a core body of znamenny melodies remained in more or less constant and exclusive use in the Russian church, in both parishes and monasteries, from the beginning of the eleventh century until the end of the seventeenth.

Beginning in the late seventeenth century Russian liturgical music began to undergo a radical transformation—in large part as a consequence of Tsar Peter the Great’s fascination with Western Europe and the cultural reforms he enacted, but also in some part as a result of organic developments within Russian artistic and ecclesiastical culture both before and after Peter. And so within little more than a generation znamenny chant and its daughter forms came to be supplanted in many places by new compositions and arrangements in the prevailing Italian style of the day. However, this period, known as the Italian Period, which saw such excesses as the performance of operatic-style works on non-liturgical texts during the Divine Liturgy (during which the assembled congregation was sometimes known to applaud with claps and shouts of “Bravo!”), did not last much more than a century.

By the turn of the nineteenth century many composers and churchmen in Russia had begun to seek a return of liturgical singing, if not to its authentically Russian and Orthodox roots, at least to something more simple and pious than the highly ornate and largely secular approach to church music that had come to prevail. These men — among whom were Dmitri Bortniansky (himself trained in Milan and well-versed in Italian music), Priest Pyotr Turchaninov, and later, Fyodor and Alexei L’vov — looked to the surviving body of canonical chants as the foundation upon which they might build a synthesis of traditional Russian chant and the European four-part choral style which had by this time become firmly fixed in the Russian ear. The fruit of this work is the truly vast body of Russian liturgical music that came to be known as obikhodnaya, or “common” chant. To this day, common chant (sometimes referred to as “Court Chant”), in various rescensions and rearrangements, continues to be regarded as normative in much of the Russian Orthodox world. However, the fact that common chant became ubiquitous should by no means be inferred to mean that it was, or is, universally admired. It sustained a good deal of criticism during the first years of its appearance in the early to mid nineteenth century, and it probably would not have caught on nearly as well as it did were it not for its use becoming legally mandatory through the energetic support of Tsar Nicholas I.

The main criticism leveled at common chant is the fact that, although it was based on pre-existing canonical chants, it often truncated and simplified these chants to the point that they became virtually unrecognizable. The resulting melodies had little to recommend them apart from their ever-present four-part harmony accompaniment, devoid as they were of much of the distinctive melodic and rhythmic vitality of the original chants. As the nineteenth century progressed, more and more churchmen and musicians began to grow weary of the relentlessly formulaic common chants and the system of Imperial censorship that protected them. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century — aided, on the cultural side by the rise of Russian nationalism, and on the spiritual side by the resurgence of traditional coenobitic monasticism at Optina and other major monastic centers across Russia, and helped along in no small part by the collapse of Imperial musical censorship in an historic court battle in 1880 — interest in authentic Russian chant, and in znamenny chant specifically, enjoyed a significant revival. Through the work of the Moscow Synodal School of Church Music and its leading figures, such as musicologist Stepan Smolensky and composer Alexander Kastalsky, along with many others, collections and arrangements of, and new compositions based on, znamenny chant and its variants began to be published and widely disseminated, for performance by both large and small ensembles. By the time of the revolution in 1917 the workings of a thoroughgoing chant revival had been set in motion, such that church musicians both in and out of Russia were able on some level to continue work on transcriptions, arrangements, and publications throughout the Soviet period, despite state repression and lack of sponsorship. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s such efforts have only been redoubled.

While criticism of common chant in Russia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries tended to proceed along purely aesthetic lines, a more practical problem with common chant has arisen over the past half century among the heirs of Russian Orthodoxy in the New World. In pre-revolutionary Russia competent singers who could amply fill the ranks of church choirs were usually in ready supply, and so music like common chant, that depends almost entirely on a strong and sonorous four-part texture, presented little practical difficulty. However, in twenty-first century America, where many Orthodox parishes are struggling to sustain a regular and committed choir, and where musical culture and education have suffered a sharp overall decline — a decline that affects cradle Orthodox and converts alike — staffing parish choirs with even one skilled singer per voice part can sometimes be a major practical challenge. Given these circumstances, the persistent use of common chant in American parishes has resulted in singing that is alternately colorless and uninspiring; at times pleasant, but musically unbalanced because voice parts are either weak or completely missing; or other times, so egregiously out of tune or verbally inarticulate (or both) that it becomes extremely difficult for the faithful to remain prayerfully attentive during services. Of course, common chant cannot bear all the blame for this state of affairs. However, its basic lack of a vital melodic core that a few amateur singers can sing satisfactorily, and its subsequent wholesale reliance on four-part harmony, make it an increasingly ill-suited body of repertoire for the needs of today’s American church choirs.

In recent decades — and especially since the advent of the internet — a large amount of music that offers an alternative to common chant has begun to be published in English, much of it of good quality and available free of charge. It has now become possible for American church choirs to fill the better portion of their repertoire for the liturgical year with melody-based chant transcriptions and chant (or chant-like) arrangements acquired solely from online resources. However, up to now a major gap in the repertoire has been music for the Panikhida and Burial services. Hitherto, the only music for these services readily available in English was based entirely on common chant settings. Sadly, since funerals and Panikhidas are often semi-private services in practice, sung by only a handful of pick-up singers or even just by a priest alone, the rendering of these services in an inspiring, expressive, and uplifting manner tends to be a somewhat rare event. This is especially unfortunate, given that funerals and Panikhidas are (1) services in which spiritual consolation and inspiration are greatly needed; (2) they are often attended by infrequent churchgoers or non-Orthodox, and are thus unique points of contact with the Church that leave a lasting impression; and (3) they contain some of the most moving and spiritually instructive pieces of hymnography anywhere in the Orthodox liturgical cycle, whose significance, when the hymns are sung unclearly or unmusically, tends to be lost on most listeners.

As much as possible we have aimed to preserve in any new settings the overall character of the Panikhida and funeral melodies that have become familiar to many Orthodox in the Russian tradition, and in some cases have elected to use common chant where we have deemed it desirable, providing alternate settings immediately afterwards in the text. However, where the music in this volume departs from familiar settings, we have done this with an eye towards (1) reconnecting the music for these services with the broader and more ancient living tradition of Russian chant; and (2) giving the words of these hymns a real home in the English language in a way that allows their spiritual power to penetrate deeply into the hearts of reverent listeners.

Will there be an E-Book release?

This is wonderful! I can’t wait to order a copy.

Is there any update on this book?

Just to check, am I correct in assuming that the Panikhida and Burial music in this book are in this CD recording-http://www.stspress.com/products-page/sts-press/page/3/ ?