Similar Posts

Parishes in the Wilderness

Orthodox parishes in Britain often have to share a church with Anglican parishes. Before each service they will usually need to set up all the furnishings and icons needed for Orthodox worship, then put them all away again at the end. It’s all quite tiring, both emotionally and physically, so the easier this moving can be done the better. I was approached about three years ago by the priest of St Ephraim’s Russian Orthodox parish in Cambridge to make an icon screen, but it had to be retractable for this very reason. The community was about to enter a long-term lease with an Anglican parish to share its church. This article is about the making of the screen.

There are various reasons why fledging Orthodox parishes in Britain cannot usually buy or build their own church. In its early life the parish is usually too small to raise funds to buy its own property; real estate is quite expensive in most of Britain compared to less densely populated countries. Also, because of poor Sunday public transport to outlying areas it might be important for the parish to locate near to or in the town centre. Spare property is notoriously rare in inner cities, and if available, is notoriously expensive.

The Brief

Such was the case with the Russian Orthodox community in Cambridge, England. Two years ago the parish of St Ephraim – and almost fifty years after its foundation by Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) – signed a lease to share the ancient church of St Clements with its Anglican owners. The church is right in the centre of the famous and historic university city of Cambridge, is large, and has meeting rooms. So it was ideal in most respects, but the lease required that the iconostasis and any other furnishings be moved out of the way after each service.

The community had been like the Israelites in the desert for a long time, with no fixed abode. Father Raphael Farmour therefore wanted his parishioners to feel that their new iconostasis looked permanent when up, and yet be very easy to open and close for use. Added to this we wanted the design to harmonize with the existing architecture and furnishings while also being true to the Orthodox ethos. A challenging brief to say the least!

After numerous setbacks, in March this year the screen was finally completed. I had designed it, made its icons, and painted and gilded the ironwork. Master blacksmith Frazer Picot made the screen itself. To our relief the hinged screen opens and folds away easily, despite the challenges posed by the uneven tile floor.

So how does the screen work? It is in two parts, each made of two sections hinged in the middle above and below the deacons’ doors, with the outer one hinged also to the walls. When not in use, with the help of castor wheels the two parts fold away concertina-like against the north and south walls. The Royal Doors fold away out of harm’s way behind the inner two sections.

We made handles that can be folded out when the screen is being moved, so the icons and frame need not be touched when opening and closing. The structure is made of mild steel, the epistyle being a box structure and the rest solid bar. Frazer made most of the joins using traditional mortice and tenon joints but also welded them for extra strength, an important element given the stresses the screen is submitted to when opened and closed. All the scroll work was hand forged, some of it welded using the traditional fire welding system.

The curtain rails with curtains are swiveled out of the way against the epistyle before the screen is folded away.

The Design

We wanted the screen to harmonize with what existed. A low wrought iron chancel screen was already there, which led to the idea of using iron rather than wood for the screen structure. I took elements from this for the ornamentation, as well as from a splendid nineteenth century pulpit at Lichfield Cathedral, designed jointly by the famous architect Sir George Gilbert Scott and the ironworker Francis Skidmore, and executed by the latter.

The polychromy and gilding on this pulpit also gave me the idea of doing something similar on the Cambridge screen to warm up the otherwise cold ironwork. The colours were chosen to harmonize with those on the rood beam sited above the screen.

The epistyle had to be of quite a large cross section to deal with the stresses when opening and closing, which meant that it called out for some decoration. The gilded design on it is a vine motif which springs from the Cross placed over the central arch. The Cross also serves to cover the gap where the two halves of the screen meet.

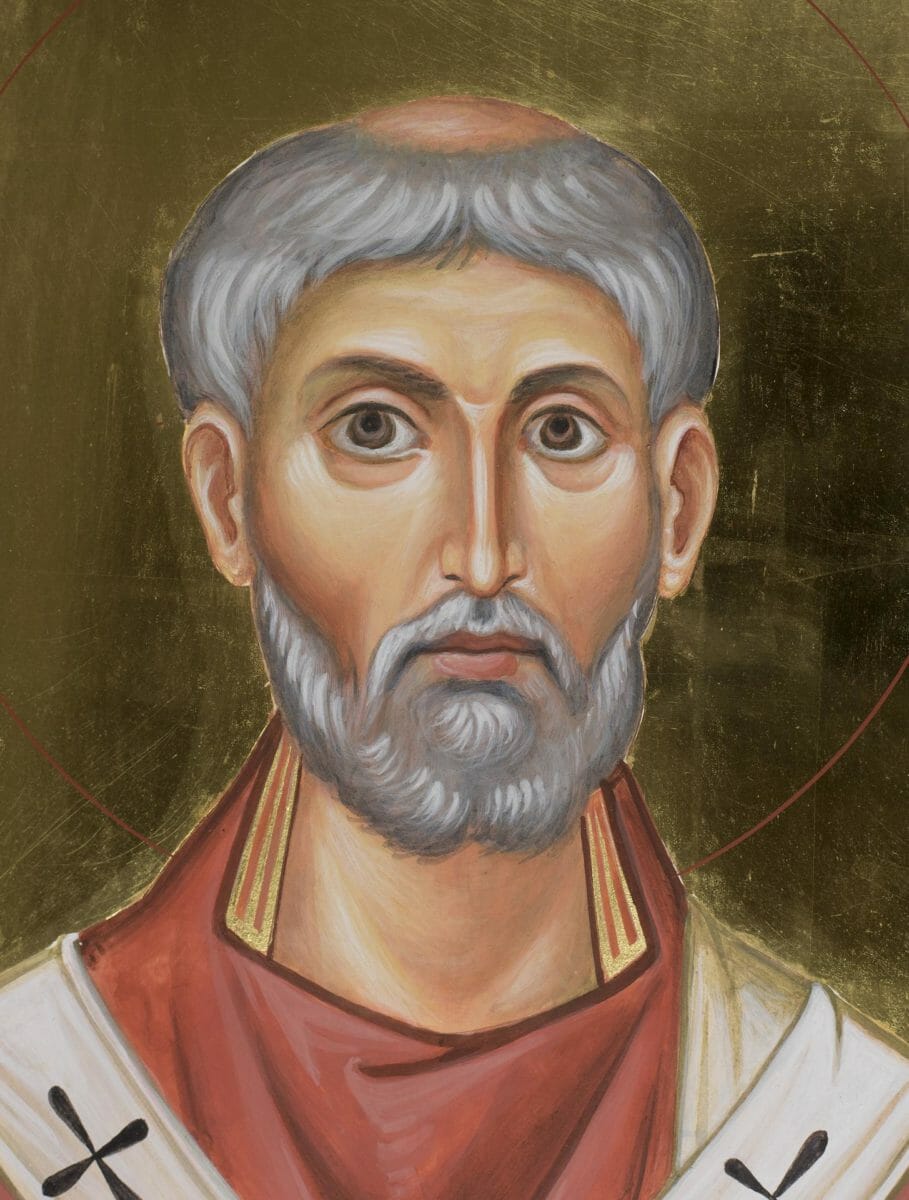

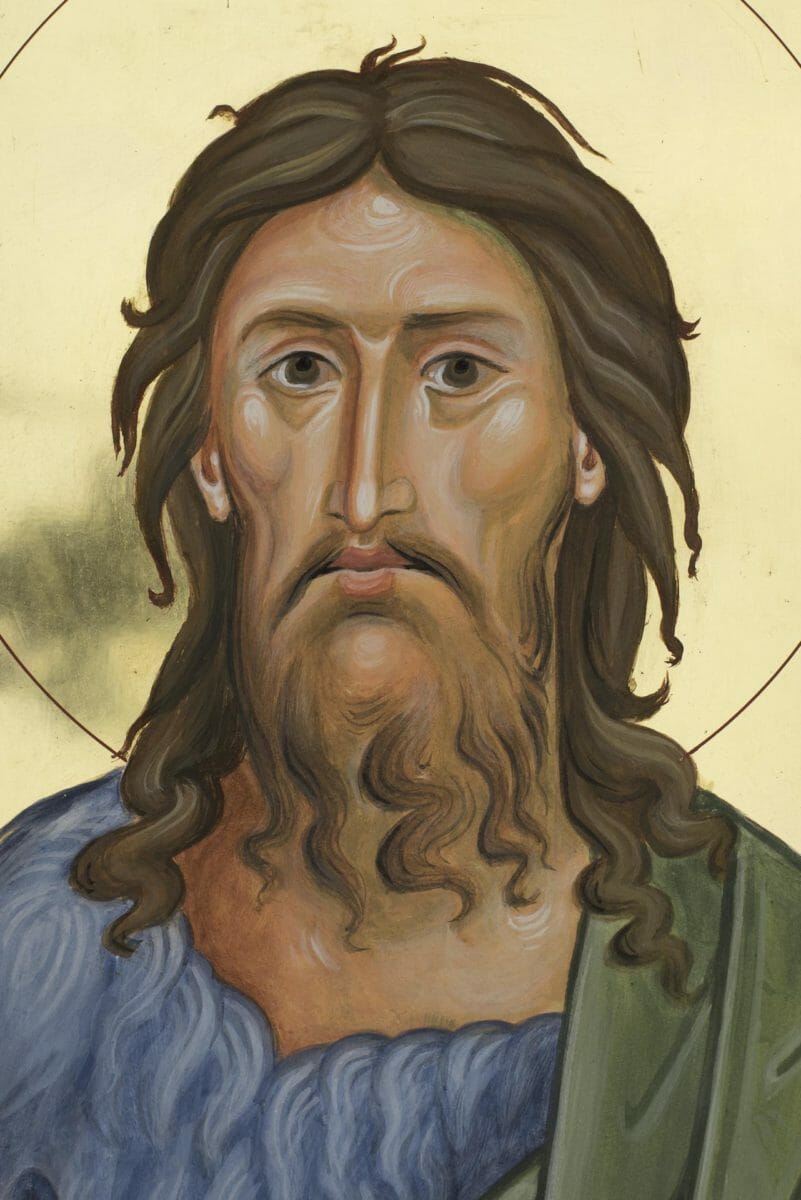

Holiness unites and at the same time distinguishes, each saint being given by God their unique name. I tried to reflect this in the faces of the saints painted for the screen. St Clement, Pope of Rome (martyred around 99 AD) for example, is given the quiet dignity that befits a bishop. John the Baptist by contrast has the weather-worn face of a fasting ascetic of the desert, but at the same time has the aristocratic demeanour of someone renewed in God’s likeness.

The screen has proved very popular with the Anglican community as well as with the Orthodox, event to the point of them wanting it left open during the day for the many daily visitors to see.

Aidan Hart’s Website can be found here.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Thank you, Aidan, for sharing this beautiful project. I can imagine how difficult it was to make this function well and also look just right. It’s quite an accomplishment. I particularly love the perfectly Victorian-English style of the ironwork. I remember iron just like that from so many British churches I’ve visited, and also a few Anglo-Catholic ones here in the USA. It’s quite culturally distinctive, and marries beautifully with your iconography. Your work has convinced me that iron can be a very good material for an iconostasis. I would consider it even in a church where the screen doesn’t need to fold.

That is exceptional work, beautiful and ingenious all at once. It’s a wonderful testament too that the Anglicans like it enough to allow it to remain in place for visitors to see, despite it being technically stowable.

What is the weight of the icon screen?

I feel so fortunate to have seen some of the icons at your course at Walcot last September – the whole work is uplifting and beautiful – and I particularly like that the Anglican community are appreciating this as well.

Thank you all for your encouraging comments. One of the secrets is to find an expert blacksmith who can execute the designs! Another challenge is to balance the technical requirements with the aesthetic – not to have the metal thicker and heavier than necessary. Also, to have any decoration serve the icons and not distract from them. I think an iconostasis should be like a royal throne: worthy of the king or queen, but not so fancy that you notice the throne before the royal sitting on it!

Each half of the screen weighs approximately 135 kg (300 lbs), including the icons. Because of the design, it is quite easy to open and close – an elderly person can do it. The only time a tug is required is the initial movement to get it started, because the castor wheels are pointing the wrong way from the previous move.

Truly awesome. While stationed in the UK as a U.S. Air Force chaplain at RAF Mildenhall -just a few miles away – I often visited St. Clement’s.

At the military chapel I had a modular wooden iconostasis built in nine lightweight parts that a chaplain assistant could put up or take down in less than five minutes. Necessity can still be beautiful. I thought our solution was well constructed and beautiful, but the icon screen at St Clement’s is even more beautiful.

Hello Fr Lawrence. Your blessing. If you have a photo of the Mildenhall screen it would be great to see it. I am always on the lookout for solutions to liturgical challenges!