Similar Posts

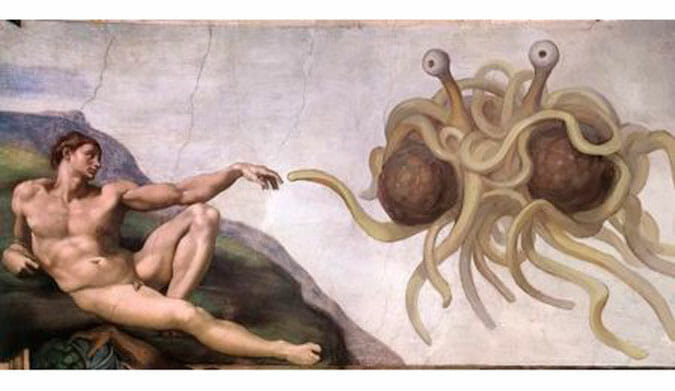

The Logo of the “Flying Spaghetti Monster Religion” shows Atheism to be the final result of believing God to be a an arbitrary “being” which either “exists” or does not “exist” within the sphere of knowledge.

My priest recently sent me a link to a talk (posted below) given by Matthew J. Milliner, an assistant professor of art history at Wheaton College, which was quite astounding to me. The talk tackles two subjects quite adroitly, two subjects, which Orthodox thinkers have addressed for some time now. Firstly he tackles what is being called the “declinist narrative” (even it seems by some contemporary Evangelical scholars). He expounds the notion that an important theological shift occurred in Medieval Scholasticism (Occam, Dun Scotus) which closed off the classical analogical and anagogic possibilities of language and of the cosmos itself. This change would be the seed of the modern world, of desacralisation, of atheism, of totalitarianism, etc. Mr. Milliner refers to the problem of the “univocity” of God as presented by Dun Scotus, that is how the qualities ascribed to God are seen as not being analogical to the unknowable Divinity, but are rather “univocal” to God’s very nature. So according to Dun Scotus, when we say that God is good, his goodness is the same as our goodness, but his goodness is just far greater than ours. In this way, God is seen as a “thing” that has really really lots of great qualities. He explains and shows how traditional metaphysics are rather analogical in approach, that is both pointing to the resemblance and dissemblance between God and creation simultaneously. He offers this wonderful quote by the Aeropagite:

God is at total remove from every condition, movement, life, imagination, conjecture, name, discourse, thought, conception, being, rest, dwelling, unity, limit, infinity, the totality of existence, … and yet… to praise his divinely beneficient Providence you must turn to all of Creation.

This is what Orthodox have come to call the “apophatic” and “cataphatic” approach to God, both resumed together in the very movement of analogy.

Now as if an Evangelical quoting an excerpt from “The Divine Names” is not surprising enough, he goes on to his second point. He continues by suggesting that this problem, this crisis if you will, can be most clearly seen through the appearance of depictions of God the Father in visual arts at this very epoch. Mr. Milliner connects these two developments, that is the theological change within Scholasticism on one hand, and the artistic change on the other in a wonderful and compelling way. The central notion is that an image of God the Father, by representing him within the sphere of knowledge, reduces the unincarnate, uncreated Deity to “a bearded old man on a cloud”, maybe an ultimately invisible bearded old man on a cloud, but a “being” nonetheless, who in the final analysis could be believed in or not. Similar points have been argued by several Orthodox thinkers, such as Leonid Ouspensky and our own fr. Steven Bigham (both of which Mr. Milliner mentions). He goes on to show how efforts both in the Catholic Church and Orthodoxy have failed to remove this image, despite knowing (especially the Orthodox) its danger. The suggestion is made that the root of Protestant iconoclasm were these types of representations of God. He even comments, with tongue in cheek, that if the P-Riot ladies really wanted something to protest when they staged their little punk liturgy, they should have looked up to the image of God the Father in the dome of Christ the Savior Cathedral.

Interestingly enough though, the third point he makes is that Protestantism might have solutions to this, Evangelicals even. He then develops a surprising theory in which he casts the development of landscape in Protestant Europe as recapturing or continuing the type of analogy which was lost at the end of the Middle Ages. These works, especially that of the Romantics would be a way of representing the majesty of God the Father “in his absence, as the image of his consequences”. Basically he suggest that landscape painting, rather than being the harbinger of secularism it is usually seen to be, is rather a preservation of the traditional Christian world view.

I think we can totally agree with him that landscape painting is indeed a particularly vivid embodiment of Protestant ontology and maybe even spirituality. But is it in line with the Medieval analogical worldview? Here is where I think we must diverge with Mr. Milliner. There is in fact an aspect missing in Mr. Milliner’s presentation. He emphasizes how univocity destroys analogy, but there is a second face to this destruction of the traditional world view. The analogy is a double movement, a showing and a removing, a relation which shows both absolute transcendence and absolute immanence simultaneously. Mr. Milliner is therefore missing that other danger, the danger of presenting God as so completely transcendent as to cut him off from the created world, making him absent from it. It is the very image Mr. Milliner uses of God as being represented “in his absence, as the image of his consequences”. In this view of the world, we do not have analogy, but rather the seed of Deism. The two aspects of late medieval scholasticism, that is univocity on one hand, and nominalism or basic Occamism on the other, are just two sides of the same coin. They are the ripping apart of the double movement of analogy, the radicalization of either believing God to be just another (albeit powerful) being, or believing him so absolutely transcendent as to finally be totally absent, present only in “the image of his consequences”. This radicalization, this incapacity for analogy is both in images of God the Father AND in the rise of the purely visual, anecdotal or highly emotional representations of the cosmos of which landscape is just one of the manifestations among many within the “declinist narrative”. Both opposites in the analogical dismemberment, even the radical transcendence of God which on the first hand may seem superior, in the end reduce God to necessity of some kind. The radical transcendence of God as can be found so strongly in William of Occam, ends up making God into a no less arbitrary “exterior being”.

The only possibility of recovering the analogical world of the Middle Ages within Christian Art is through the person of Jesus Christ, who is the express image of the Father. Mr. Milliner makes a point about Christ being the image of the Father in passing. He quotes St-John of Damascus saying “I do not depict the invisible divinity… …but I depict God made visible in the flesh”, yet he fails to hone in on this. In fact he fails to make Jesus Christ the center of his discourse. To miss this is to miss everything. There are some images of divine absence in Christian tradition, the “hetymasia” being the most common, but the Church has truly made the image of Christ the central image of all of Christian art, an act consecrated by the 7th ecumenical council. Indeed, the entire web of cosmic analogy is held together by the the incarnation: the human and divine completely united while remaining completely separate and without mixture. All the cosmos points to Christ, who is the head, “from whom the whole body fitly joined together and compacted by that which every joint supplieth, according to the effectual working in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the body unto the edifying of itself in love”. What better description is there of the analogical world than this passage from St-Paul? By seeing this we will grasp why “landscape”, or more specifically representation of foliage and animals were not abandoned in the Middle Ages, but were rather placed in peripheral guises, as ornament, hierarchically arranged in the “measure of their parts”. The center, the true and only image of God is the renewed Man, the new Adam, Jesus Christ himself.

Above and beyond the representation of God the Father, which IS heretical, the analogical perspective remains at the core of Orthodox life, theology, ecclesiology, spirituality and art. The success of St-Gregory of Palamas and the proclaiming of the Essence/Energy distinction over the pervasive scholastic theology of the time, ensures that the core is still there despite the real and undeniable ravages of modernism. On the other hand, if Protestants pursue this line of thinking, this declinist narrative, it will inevitably show how the very radicalization of opposites I have described, the very ripping apart of the analogy, is what gave birth to all the conflicts of the Reformation: The opposition of predestination to free-choice, the radicalization of faith vs. works, the opposition of “interior” spirituality with exterior form, the progressive evacuation of all sacramental reality. In fact, when one takes this road, it is impossible not to notice that the very fabric of Protestantism is woven with nominalism and univocity.

Despite my last objection, my heart is smiling, for this vision of the world is the key. If we are to develop what Mr. Milliner beautifully calls “a metaphysical ecumenism”, if Orthodox, Catholic and Protestants can truly recapture the metaphysics of the early church, then to follow the analogy itself, to follow the very movement of manifestation from the inner to the outer, we will not be far from true and actual communion. And so this talk is quite worth the time to engage with and shows hereto unheard of points of contact between Orthodox and Evangelicals, points which it would benefit us all to pursue.

The talk can be seen here: http://youtu.be/JdaBe0dFsTI

…never suggested that the FATHER is MALE… There are many words for a non-male or neutral progenitor. ‘Parent’ is one of them, ‘father’ is not.

This was a really good essay. I believe evangelicals are parroting some of these lines about medieval development from Mark Noll, which is fine, but the next step seems to be to try to work out independent trajectories that frankly don’t make much sense. As much as I find iconography involving an old man regrettable, there is at least the rationale of the Ancient of Days. I can find no way at all to avoid the same criticisms you develop with respect to Milliner.

[…] article was originally published on the Orthodox Arts […]

To continue my general rear-guard action, I would point out as usual that Scotus does not deny the analogy of being, and from what I have read of the Scotist school, they harmonize analogy and univocity. furthermore, many elements of his thought are Dionysian in inspiration (divine ideas, unitive containment, etc.). Oddly, your discussion of how Christ should be at the center of art, etc., is fully in line with Scotus’ own position on Christ and the incarnation as being the peak of creation and the general Franciscan interest in the humanity of Christ.

But I suppose that it is necessary to have the black legend of Scotus in order for Protestants, Orthodox, and Catholics to unite in love and harmony.

To be honest with you, I am certainly not an expert on Duns Scott and know him only from secondary sources. So it is quite possible that you are right, since it is commonplace today to try to find “the culprit”. In a similar manner you will find Orthodox writers trying to put all of Western malaise into St-Augustine or Thomas Aquinas. One thing is certain, that is how between Abelard and Luther, something changed, a true shift in thinking which cut off all true Ontological hierarchies. In this regard and specifically for this video and my article, what matters is that this shift can be seen in ecclesiastical art as images of God the Father become prominent. The shift, like I tried to show, is not just in a type of radical univocity, but also the radical transcendence of God seen in much protestant discourse, both of which sent the world on a pendulum swing that would move with a more and more extreme opposition into the modern age.