Similar Posts

The Exhibition

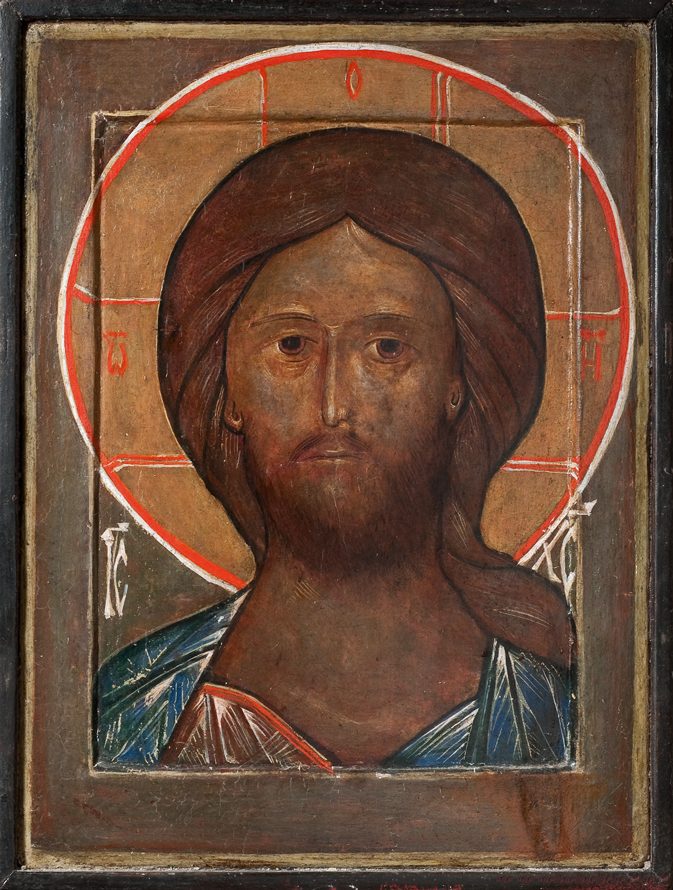

In late June, I was blessed with the opportunity to spend a week in Paris, attending an exhibition in honor of the 50th anniversary of the repose of iconographer monk Gregory Kroug. The event ran from May 14th through June 30th, and included a curated exhibition of Kroug’s iconography displayed in the Russian Cultural and spiritual center of the Holy Trinity Cathedral; tours to the various churches that are home to his icons and wall-paintings; and various lectures and publications. In my 2016 OAJ interview I discuss the influence Fr Gregory’s work has had on my own iconography. I have studied his work from photographs for years, but nothing could have prepared me for the experience of encountering his work in person.

The exhibition was organized by Emilie Van Taack, my gracious host in Paris, herself an iconographer and teacher in the tradition of Leonid Ouspensky, who was her teacher until his repose in 1987. Emilie organized an exhibition of Ouspensky’s icons in 2017. Kroug and Ouspensky were lifelong friends and colleagues, venturing together into the study and practice of Orthodox iconography. The depth of their search for Christ through the icon has made these two men among the most influential iconographers of the modern era, whose impact we are still only beginning to see.

Father Gregory’s Life 1

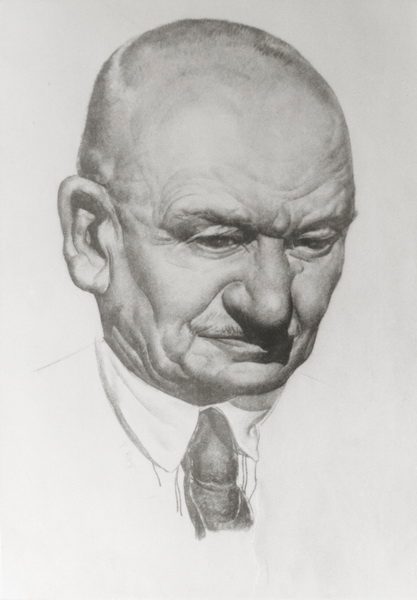

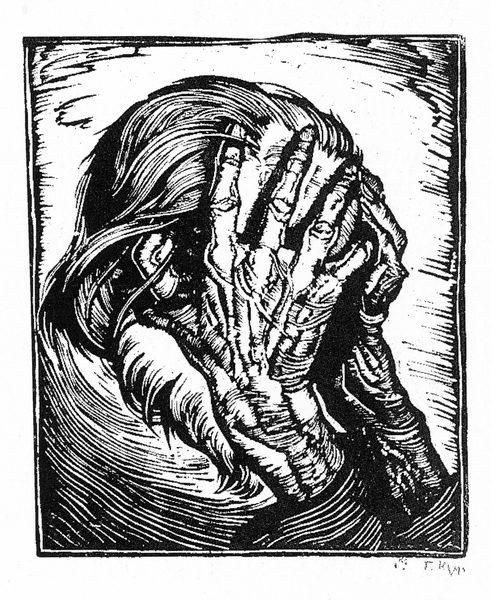

George Kroug, the future Fr Gregory, was born January 5, 1908 into a prosperous family in St Petersburg. His father Ivan Feodorovich, was a Lutheran who worked in industry. His mother, Paraskeva Souzdaltsev, was an Orthodox Christian and a pianist. George and his sister Olga were raised in the Lutheran tradition, and received a progressive education that emphasized the arts. After the 1917 Revolution conditions worsened and a devastating famine arose, causing the family to flee to Estonia where they were able to obtain citizenship following the 1921 Estonian independence. There George enrolled in art preparatory schools and studied drawing, watercolor, and printmaking. At age 19, George attended an Orthodox retreat where a mystical experience led him to convert to the Orthodox Church.

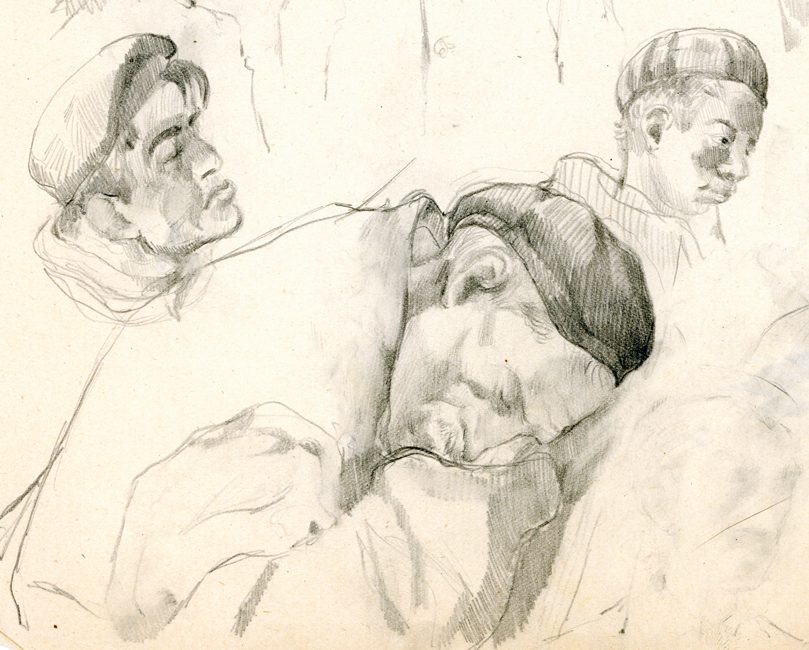

In 1929, the family learned that Leo Tolstoy’s daughter, Tatiana Lvovna Sukhotine-Tolstoy, had founded a school of fine art in Paris which focused on oil painting, taught by well-known artists. George was eager to go. Together with his mother and sister, he emigrated to Paris in 1931 only to find the school closed. However, some of the teachers, led by Nikolai Milioti, had agreed to continue teaching a zealous group of students free of charge. George joined this group. Leonid Ouspensky was one of his classmates, and the two became lifelong friends. They spent the summers at the dacha of their teacher Konstantin Somov, where they executed many lively portraits and drawings. 2

Ouspensky soon had a powerful conversion experience as well, directly related to his encounter with iconography. Before long the two artists began their journey into the icon. Ouspensky was quicker to abandon all other forms of art in favor of iconography, while Kroug maintained close ties with the avant-garde. He continued to work in the studio of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, leaders of the Russian avant-garde movement.

Like most of the Russian émigrés, Ouspensky and Kroug lived in poverty, but zealously pursued their spiritual and creative aims. Both joined the Brotherhood of St Photius, a group of theologians and creative intellectuals who attempted to articulate their Orthodox faith in and for the western society surrounding them. They brought their work before this interdisciplinary group for review, in search of what iconography should look like in their modern western context. At first, by Ouspensky’s initiative, the two attempted to develop a Western Orthodox iconographic style influenced by Romanesque. Together they produced little-known frescoes and an iconostasis for a small house-chapel of the Protection of the Theotokos. They worked together on the frescoes and iconostasis for the Three Hierarchs Church on rue Petel, at first also in a western-influenced style. The two iconographers collaborated often, sometimes working on the same panel together.

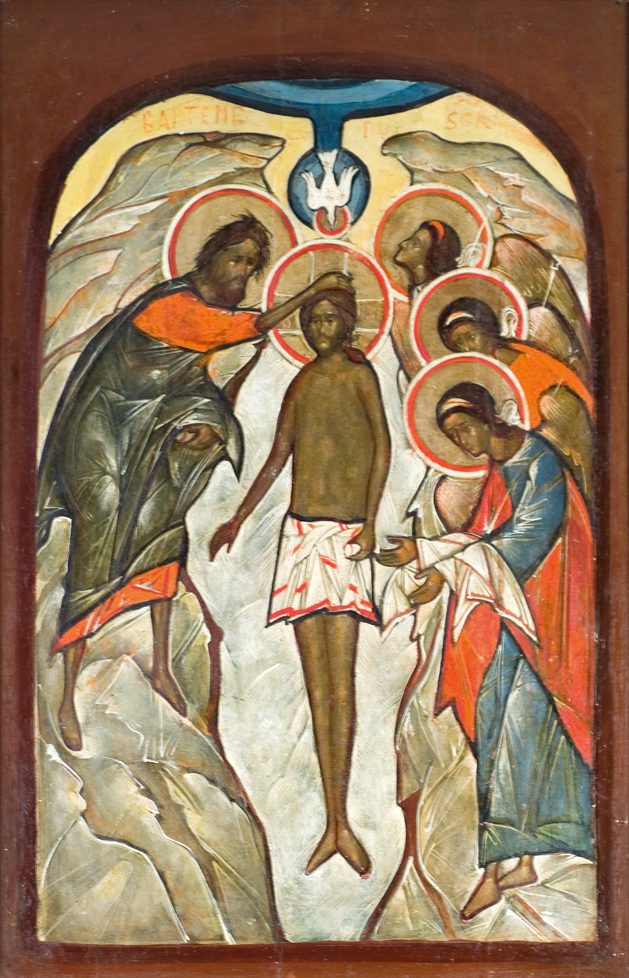

Icon of the Trinity in Western Orthodox influenced style, from the original iconostasis at rue Petel

George was deeply sensitive by nature, and from his various difficulties—the effort to paint in the Western Orthodox style that was unnatural to him, the cultural tensions involved in immigration, and the beginning of the Second World War—he became mentally unstable. A major spiritual crisis and depression brought him to a mental asylum. This took place in the early 1940’s, during the Nazi occupation of France, and the Nazi-led asylum aimed to let the inmates starve as useless to their regime. George’s sister Olga kept him and other inmates alive by trading some of the numerous drawings and watercolors George made in the asylum in the marketplace for food scraps, which she chopped, boiled, dried and ground to a powder she could covertly distribute.

George made copious drawings during his term in the mental asylum, in which one can perceive a deepening of his compassionate and reverent vision of the human person.

During this time one Hieromonk Sergei Schevich, who knew the Krougs, began to visit George almost daily, comforting and encouraging him along the path of healing in Christ. The staff there saw George’s health improving, and eventually granted him permission to return to society, at Fr Sergei’s persistent request and under his supervision. George lived with his sister, and Fr Sergei counseled him to focus on iconography as a means of healing. Soon George moved to Vanves where Fr Sergei was founding a monastic skete. He became a novice in 1945. Three years later he received monastic tonsure with the name Gregory.

In the Monastery

Though the monks lived in very strict poverty, here began a prosperous time in Fr Gregory’s life. Besides the usual monastic cycle of services, he painted icons almost continually, both in his small studio and on church walls. Fr Gregory carried out this labor of love with increasing inspiration until the end of his life.

Fr Sergei described Fr Gregory’s working method as such: He would first consider his subject, look at various examples of icons, read relevant texts, pray, and be still to envision his icon. Then, seeming to have the icon fully inside him, he would go to his panel or wall and with great speed draw it out in its entirety and lay in the colors. The icon would be nearly complete within a short time, but he followed this with an often long, slow, and caring process which he called “polishing,” whereby he brought the icon to completion.

Because of Fr Gregory’s intense battle with his thoughts, Fr Sergei would read to him from the Fathers and the lives of the Saints while he painted in his studio. No one but Fr Sergei ever saw him at work. It is said that while he painted away from the skete, for the new iconostasis at Rue Petel, he would recite psalms continuously so that it sounded like the buzzing of bees. If anyone visited him, he would stop painting and wait until he was alone to begin again. Later, when Fr Sergei was no longer living at the skete, Fr Gregory would listen to classical music as he painted. He had a special reverence for the host of the radio station, Michael Hoffmann, whom Kroug affectionately referred to as “Misha Goffmann.”

Fr Barsanuphe, who was a young monk at the skete during the later years of Fr Gregory’s life, gave this description of him:

The thing that struck you when you met father Gregory for the first time was his absolute detachment, his renunciation of the appearances and conventions of the world, and at the same time his total openness to others, the warmth and concern towards others. His interest in what everyone had to say to him was shown by the attention he showed to each individual, his presence, which made him entirely available to the person who spoke with him.

As for his detachment, it was almost spectacular, having reached such a high degree that Father Gregory paid no attention to the way he dressed, to the worn-out of state of his clothing or conventions related to cleanliness, neatness and appearance. This was all the more evident when he was painting icons, for he was so absorbed in his work he would often wipe his hands or his paintbrushes on his monastic habit or his hair, leaving the most diverse colors about him. But what could have been an object of ridicule for some was, for us monks, a source of edification. When you spoke with him, you completely forgot how he was dressed and his appearance in general. 3

Father Gregory’s Work

Fr Gregory is known for his great freedom of expression in visual language and subject matter, as well as his strict adherence to the tradition of Byzantine iconography and Orthodox theology. While he neither taught nor wrote much, he was in close contact with profound spiritual leaders, theologians, and iconologists, including Leonid Ouspensky. Vladimir Lossky, a friend and fellow member in the Brotherhood of St Photios, would speak with him in detail about theology, and once remarked, “he understands every nuance with such finesse!”

Fr Gregory never named a price for his icons. His abbot Fr Sergei would manage his commissions, which were generally paid for as a voluntary gift to the skete. Fr Gregory would often give away icons freely to people who asked him, however poor. The poverty of the community of Russian refugees in Paris, in which Fr Gregory shared both physically and spiritually, is one source of the pastoral inspiration of his work. We see this in the warmth and immediacy of personal presence in his icons; the combination of deep poverty of spirit with joy in the victorious light of Christ.

Fr Gregory made most of his work for this Russian community in exile, people whose lives were very difficult. It is through his ministry to this very specific context that Fr Gregory’s icons are able to speak more universally to people of our often turbulent and psychologically complicated times. He painted the icons for a shed-turned-chapel on a small farm which Mother Maria Skobtsova turned into a refuge for the homeless in Noisy-le-Grand. In Montgeron, an orphanage for Russian children who lost their families during World War II, Fr Gregory painted icons whose tenderness and warmth have made them beloved throughout the world, including his famous icon of St Seraphim for whom the orphanage is named. He made his greatest program of wall-paintings for the small Skete of Our Lady of Kazan in Moisenay which housed an old folk’s home along with a small group of nuns.

Before his monastic years, Fr Gregory also painted icons for a shack that was used by a community parishioners at Rue Petel, which for a time included Fr Sophrony Sakharov after the latter’s return from Mount Athos. The spiritual quality of these icons so impressed Fr Sophrony that he asked Fr Gregory to make the iconostasis for the monastic community he began in France. This iconostasis now stands at the monastery Fr Sophrony founded in Essex, England.

In his later years, Fr Gregory rarely left his cell, but painted icons continually despite suffering from numerous and unusually painful illnesses. In the Spring of 1969 Fr Gregory was very ill and in the hospital, suffering from long untreated diabetes and stomach cancer. His ailments were incurable, and he returned to the Skete, where he decided to paint an icon for his doctor: The assurance of Apostle Thomas as he touched the wounds of the Risen Christ.

This large panel icon is brimful of an intense and otherworldly light, astir with the gentle surge of mutual desire for encounter between the human and the divine. On the day of Fr Gregory’s repose his fellow monks came into his room to find that he had quietly died in his hospital bed, the nearly completed icon on his knees, and his paintbrush in his hand.

Fr Gregory died while painting this last icon of Thomas’ encounter with the Risen Christ. This icon was present along with many others at the central exhibition in Paris.

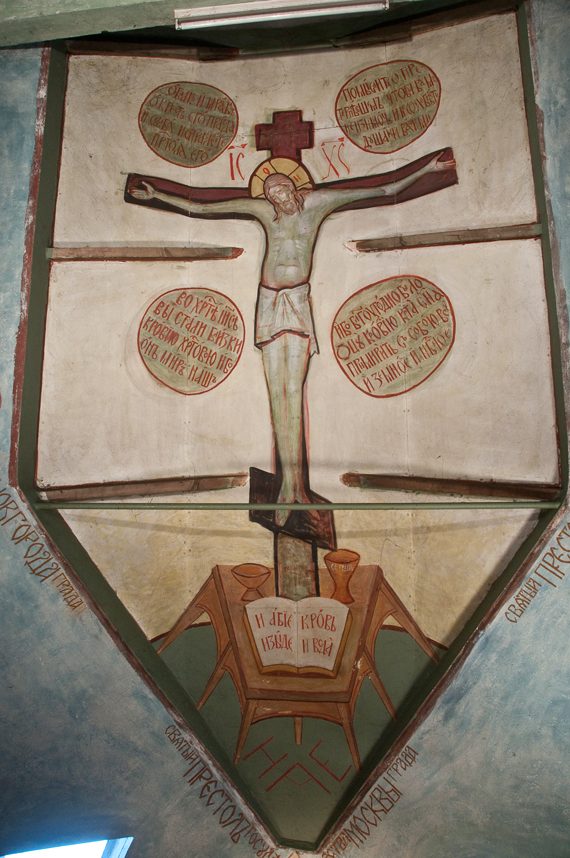

Wall-Paintings and Iconostases

In addition to the curated display of panel icons, the recent Paris exhibition included tours to a number of churches where Fr Gregory painted: The Church of the Three Hierarchs at Rue Petel, The Skete of our Lady of Kazan in Moisenay, the Church of St Seraphim in Montgeron, and the Skete of the Holy Spirit in Mesnil Saint Denis where Fr Gregory lived. I include a few pictures to give a sense of each place. This list includes every place where Fr Gregory made wall-paintings, but his iconostases and panel icons also exist in other churches and private collections.4

Nave of the Church of Our Lady of Kazan in Moisenay, Fr Gregory’s fullest program of wall paintings.

Reflections

What impressed me most in my encounter with these icons is their transparency, not primarily of paint layers, but of spirit. It is a thing difficult to translate into words, but I will try to give some sense of what I mean by “transparency of spirit.”

As a devotee to whom Fr Gregory’s icons appeal deeply, my impulse was first to analyze, to store and memorize a catalogue of ideas and strategies for future reference. This created anxiety in me, especially as these aims are manifestly impossible. Fr Gregory apparently eschewed every formula in favor of continual poetic visual responsiveness, always looking with fresh eyes in readiness for an unexpected solution or revelation.

With time and some guidance from my host Emilie, I gradually let go of this impulse. As Emilie says, we can only imitate Fr Gregory “from the inside;” that is, by learning from him to love that transparency of spirit. As I struggled to part myself from the Chapel at the Moisenay Skete, wishing I had more time to look, I noticed a bird’s song kept interrupting my anxious mind, and I remembered a phrase of Ouspensky’s that someone had quoted to me – “Fr Gregory paints as the bird sings.”

Creativity in icon painting can take the form of finding impressive or unusual styles; of calculated drafts from ancient iconography or modern art, or of making display of skill and virtuosity. Such approaches receive all the more fuel from the mass availability of models through Google Images, Social Media, printed publications, and the like.

Kroug and Ouspensky had limited access to models. They looked for old icons at the Paris antique market and studied these deeply for hours. Both men turned to the icon first of all through their own need for healing in Christ, and icons became a conduit of this healing both for them and through them for their community. The vitality of this need motivated them to seek the essence of what speaks and heals through icons.

The methods Fr Gregory finds may appear inexplicable and bizarre, however beautiful, when we study his work as an end in itself; an object of study or artistic analysis. But they begin to make a new kind of sense when we encounter them as they are – as a meeting place with the divine, a conduit of personal contact with Christ. The whole icon, as a unified composition, with its own inner order and emphasis and spirit, as it were, joins in the movement of prayer, allowing one’s spirit to pass freely. This is the meaning of that transparency for which Fr Gregory labored in everything – he was whisperingly sensitive to anything that might interrupt that flow of love through the icon – any visual imprint of showing off, of impressiveness, prettiness, sentimentality, or preciousness, as well as any show of carelessness, crudeness, or irresponsibility.

However countercultural, an iconographer labors to “get out of the way” – to be a channel rather than a fountainhead of the image. Fr Gregory’s own story of the need for healing in Christ opened to that of his specific community and time, and it is from there that his icons speak universally.

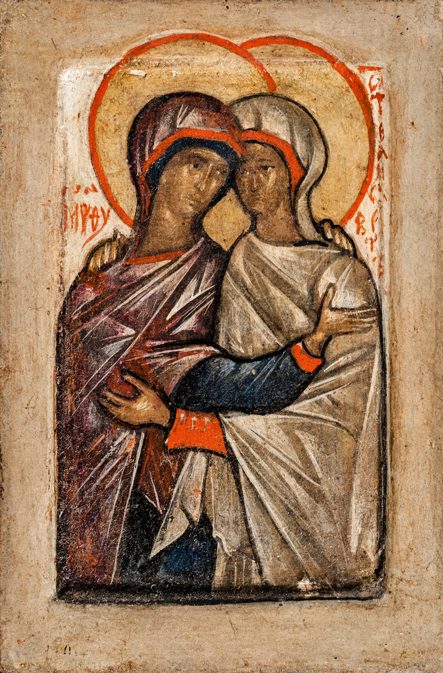

Icon of the Resurrection, located behind the altar in one of the small side chapels at the Skete in Mesnil Saint-Denis where Fr Gregory lived.

If you enjoyed this article, please donate to support the work of the Orthodox Arts Journal. The costs to maintain the website are considerable.

Footnotes

- I received most of the biographical information here from my host Emilie Van Taack, in our conversations during my trip to Paris. This is supplemented in places from various texts, in particular Fr Andrew Tregubov’s The Light of Christ; Fr Barsanuphe’s Icônes et fresques du père Grégoire; Fr Michael Plekon’s Living Icons; and Fr Patrick Doolan’s Recovering the Icon.

- Nikolai Milioti and Konstantin Somov were students of Valentin Serov and Ilya Repin respectively, who are amongst the most important Russian artists in history. Milioti and Somov were prominent Russians in the contemporary Paris art scene.

- Higoumène Barsanuphe, Icônes et fresques du Père Grégoire, Marcenat, monastère Znaménié, 1999 p.26

- For a full list (in French) of the places where Fr Gregory’s work is found, click here.

Thank you for the article.

I was wondering if you could tell us something about Fr Gregory’s painting materials and technique. His icons seem to be older than they are in reality. I heard somewhere that he used very poor materials to paint with (including coffee!) and this has caused his works to wear prematurely.

– Fr Justin

Hi Fr Justin,

Yes, there are some oddities. As I understand it, he had access to good pigments, and his egg tempera technique was probably good. However, he would often make his own boards from whatever he could obtain, and use casein (which he called “cheese”) in place of gesso. Both Kroug and Ouspensky preferred their painting surfaces rougher than is common in current practices. Sometimes the effect of uneven ground is quite striking.

Kroug would let his olifa oil thicken until it was nearly solid before applying it, and he would continue to rework or touch up his icons after they were varnished, using oil paint or varnish as a medium. Most likely, he would touch things up at times with whatever he had at hand. This is one of the main reasons for the deterioration.

I don’t think anyone is sure what technique or materials he used for wall paintings; in some places he attempted fresco, but he must have continued most of these in some form of secco. One big problem with his murals is the buildings themselves, which were often built by people with limited resources and/or knowledge. There has been a lot of damage due to moisture, and fungus, and the paintings darken quickly with lots of incense, candles, and people, and not so much ventilation.

I have heard of him grabbing whatever was around if it worked for his vision; shoe polish, coffee, etc. Fr Barsanuphe reports that he used garlic, polish, rotten egg whites, and vinegar… “[Fr Gregory] used to say he used everything in Creation.” Many of these things have proper uses in iconography, and it is hard to say how Fr Gregory might have used them.

It is said that some of his health problems came from licking his brushes with poisonous pigments on them. I learned that this was not just absent-mindedness. Both he and Ouspensky used their hand as a palette, for one thing, with the understanding that the warmth and the contact with skin was beneficial for technique. And, especially in order to accomplish gradations of color, would dilute their paint with their saliva by putting the brush in their mouth, again with the understanding that this was particularly good for the paint. Many of their followers continue these practices.

Ah, thanks for the detailed reply. I’m sure all these factors contribute to the distinct look of his icons. But it seems a real shame that in 200 years there may be nothing left of them.

Thank you for this incredibly interesting and enlightening article !

This is wonderful, Seraphim. It is great to have such a complete article in English for the world to appreciate his genius.

Thank you so much for this wonderful article about Fr. Gregory Kroug.

Thank you for bringing the work of Fr. Kroug to our attention. Do you have an image of his icon of St. Mary Magdalene? If so, I would be grateful for an image to my email, thank you.

I’d be glad to.

Thank you very much Seraphim for perhaps the most informative article on Fr. Gregory available in English. The comments on Fr. Gregory’s approach to materials reminds me of Photios Kontoglou’s approach to color. It is said that he used to put a bit of burnt umber in his colors in order to dirty them and make them more “ascetical”. I wonder if Fr. Gregory had a similar attitude about color and use of materials in general. His pallette tends to be somber, if not drab, mainly grays. There are moments of bright color, but it’s not his primary focus …He uses other means to speak his mind. My feeling is that his use of color creates a melancholy atmosphere. His faces also seem to communicate sadness. I wonder if this is not only a reflection of his spiritual struggle but also a clue to a general aesthetic attitude that is anti-aesthetic in the modern art sense of a rejection of classical standards of beauty. Given his previous involvment with modern art trends it doesn’t seem far fetched. What do you think Seraphim?

Hi Fr Silouan,

I think there is probably something in what you suggest, though I lack a knowledge of the particular modern art theories. Perhaps someone reading this can give more insight, or you yourself, Fr Silouan. But your comment brings a few things to ming for me:

There is a sadness about the faces in some cases, I would call it a bright sadness for sure, but it is poignant. He suffered a great deal, and he made icons for suffering people. But also, I know from students of Ouspensky that he and Kroug were very sensitive to the kind of beauty that appeals to the “taste”, and sought for something deeper. Purging that sense of taste was definitely an asceticism for them and for Ouspensky’s students, and a painful one from what I hear. Fr Gregory speaks a great deal about another kind of beauty, “saving beauty” in his notes. I tried to give my best depiction of this beauty in my description of “transparency of spirit”.

In his notes, the few I have seen translated, Fr Gregory writes more than anything about the quality of light that icons must possess to express the spiritual reality of the subject. The way things shine with the light of divinity – he writes as though he were overwhelmed by his sense of this light and its importance for the meaning of the icons. Many of his icons are composed entirely with muted colors, but oddly my main impression of them is that they each explode the palette of iconographic color, the icons vibrate with such light, such a play of warm and cool in particular, that they seem to me the most colorful icons in history. In many cases, he uses surprisingly bright strong colors, but I think even in these cases, it is the greys and muddy colors that sing the most. I have a quote here from Robert Henri that says it well:

“It is the grave colors, which were so dull on the palette that become the living colors in the picture. The brilliant colors are their foil. The brilliant colors remain more in their actual character of bright paint, are rather static, and it is the grave colors, affected by juxtaposition, which undergo the transformation that warrants my use of the word “living.” They seem to move—rise and fall in their intensity, are in perpetual motion—at least, so affect the eye. They are not fixed. They are indefinable and mysterious.” (from The Art Spirit p. 62)